I’ve had a bit more time to dig in to the paper I mentioned last week, where OpenAI collaborated with amplitudes researchers, using one of their internal models to find and prove a simplified version of a particle physics formula. I figured I’d say a bit about my own impressions from reading the paper and OpenAI’s press release.

This won’t be a real “deep dive”, though it will be long nonetheless. As it turns out, most of the questions I’d like answers to aren’t answered in the paper or the press release. Getting them will involve actual journalistic work, i.e. blocking off time to interview people, and I haven’t done that yet. What I can do is talk about what I know so far, and what I’m still wondering.

Context:

Scattering amplitudes are formulas used by particle physicists to make predictions. For a while, people would just calculate these when they needed them, writing down pages of mess that you could plug in numbers to to get answers. However, forty years ago two physicists decided they wanted more, writing “we hope to obtain a simplified form for the answer, making our result not only an experimentalist’s, but a theorist’s delight.”

In their next paper, they managed to find that “theorist’s delight”: a simplified, intuitive-looking answer that worked for calculations involving any number of particles, summarizing many different calculations. Ten years later, a few people had started building on it, and ten years after that, the big shots started paying attention. A whole subfield, “amplitudeology”, grew from that seed, finding new forms of “theorists’s delight” in scattering amplitudes.

Each subfield has its own kind of “theory of victory”, its own concept for what kind of research is most likely to yield progress. In amplitudes, it’s these kinds of simplifications. When they work out well, they yield new, more efficient calculation techniques, yielding new messy results which can be simplified once more. To one extent or another, most of the field is chasing after those situations when simplification works out well.

That motivation shapes both the most ambitious projects of senior researchers, and the smallest student projects. Students often spend enormous amounts of time looking for a nice formula for something and figuring out how to generalize it, often on a question suggested by a senior researcher. These projects mostly serve as training, but occasionally manage to uncover something more impressive and useful, an idea others can build around.

I’m mentioning all of this, because as far as I can tell, what ChatGPT and the OpenAI internal model contributed here roughly lines up with the roles students have on amplitudes papers. In fact, it’s not that different from the role one of the authors, Alfredo Guevara, had when I helped mentor him during his Master’s.

Senior researchers noticed something unusual, suggested by prior literature. They decided to work out the implications, did some calculations, and got some messy results. It wasn’t immediately clear how to clean up the results, or generalize them. So they waited, and eventually were contacted by someone eager for a research project, who did the work to get the results into a nice, general form. Then everyone publishes together on a shared paper.

How impressed should you be?

I said, “as far as I can tell” above. What’s annoying is that this paper makes it hard to tell.

If you read through the paper, they mention AI briefly in the introduction, saying they used GPT-5.2 Pro to conjecture formula (39) in the paper, and an OpenAI internal model to prove it. The press release actually goes into more detail, saying that the humans found formulas (29)-(32), and GPT-5.2 Pro found a special case where it could simplify them to formulas (35)-(38), before conjecturing (39). You can get even more detail from an X thread by one of the authors, OpenAI Research Scientist Alex Lupsasca. Alex had done his PhD with another one of the authors, Andrew Strominger, and was excited to apply the tools he was developing at OpenAI to his old research field. So they looked for a problem, and tried out the one that ended up in the paper.

What is missing, from the paper, press release, and X thread, is any real detail about how the AI tools were used. We don’t have the prompts, or the output, or any real way to assess how much input came from humans and how much from the AI.

(We have more for their follow-up paper, where Lupsasca posted a transcript of the chat.)

Contra some commentators, I don’t think the authors are being intentionally vague here. They’re following business as usual. In a theoretical physics paper, you don’t list who did what, or take detailed account of how you came to the results. You clean things up, and create a nice narrative. This goes double if you’re aiming for one of the most prestigious journals, which tend to have length limits.

This business-as-usual approach is ok, if frustrating, for the average physics paper. It is, however, entirely inappropriate for a paper showcasing emerging technologies. For a paper that was going to be highlighted this highly by OpenAI, the question of how they reached their conclusion is much more interesting than the results themselves. And while I wouldn’t ask them to go to the standards of an actual AI paper, with ablation analysis and all that jazz, they could at least have aimed for the level of detail of my final research paper, which gave samples of the AI input and output used in its genetic algorithm.

For the moment, then, I have to guess what input the AI had, and what it actually accomplished.

Let’s focus on the work done by the internal OpenAI model. The descriptions I’ve seen suggest that it started where GPT-5.2 Pro did, with formulas (29)-(32), but with a more specific prompt that guided what it was looking for. It then ran for 12 hours with no additional input, and both conjectured (39) and proved it was correct, providing essentially the proof that follows formula (39) in the paper.

Given that, how impressed should we be?

First, the model needs to decide to go to a specialized region, instead of trying to simplify the formula in full generality. I don’t know whether they prompted their internal model explicitly to do this. It’s not something I’d expect a student to do, because students don’t know what types of results are interesting enough to get published, so they wouldn’t be confident in computing only a limited version of a result without an advisor telling them it was ok. On the other hand, it is actually something I’d expect an LLM to be unusually likely to do, as a result of not managing to consistently stick to the original request! What I don’t know is whether the LLM proposed this for the right reason: that if you have the formula for one region, you can usually find it for other regions.

Second, the model needs to take formulas (29)-(32), write them in the specialized region, and simplify them to formulas (35)-(38). I’ve seen a few people saying you can do this pretty easily with Mathematica. That’s true, though not every senior researcher is comfortable doing that kind of thing, as you need to be a bit smarter than just using the Simplify[] command. Most of the people on this paper strike me as pen-and-paper types who wouldn’t necessarily know how to do that. It’s definitely the kind of thing I’d expect most students to figure out, perhaps after a couple of weeks of flailing around if it’s their first crack at it. The LLM likely would not have used Mathematica, but would have used SymPy, since these “AI scientist” setups usually can write and execute Python code. You shouldn’t think of this as the AI reasoning through the calculation itself, but it at least sounds like it was reasonably quick at coding it up.

Then, the model needs to conjecture formula (39). This gets highlighted in the intro, but as many have pointed out, it’s pretty easy to do. If any non-physicists are still reading at this point, take a look:

Could you guess (39) from (35)-(38)?

After that, the paper goes over the proof that formula (39) is correct. Most of this proof isn’t terribly difficult, but the way it begins is actually unusual in an interesting way. The proof uses ideas from time-ordered perturbation theory, an old-fashioned way to do particle physics calculations. Time-ordered perturbation theory isn’t something any of the authors are known for using with regularity, but it has recently seen a resurgence in another area of amplitudes research, showing up for example in papers by Matthew Schwartz, a colleague of Strominger at Harvard.

If a student of Strominger came up with an idea drawn from time-ordered perturbation theory, that would actually be pretty impressive. It would mean that, rather than just learning from their official mentor, this student was talking to other people in the department and broadening their horizons, showing a kind of initiative that theoretical physicists value a lot.

From an LLM, though, this is not impressive in the same way. The LLM was not trained by Strominger, it did not learn specifically from Strominger’s papers. Its context suggested it was working on an amplitudes paper, and it produced an idea which would be at home in an amplitudes paper, just a different one than the one it was working on.

While not impressive, that capability may be quite useful. Academic subfields can often get very specialized and siloed. A tool that suggests ideas from elsewhere in the field could help some people broaden their horizons.

Overall, it appears that that twelve-hour OpenAI internal model run reproduced roughly what an unusually bright student would be able to contribute over the course of a several-month project. Like most student projects, you could find a senior researcher who could do the project much faster, maybe even faster than the LLM. But it’s unclear whether any of the authors could have: different senior researchers have different skillsets.

A stab at implications:

If we take all this at face-value, it looks like OpenAI’s internal model was able to do a reasonably competent student project with no serious mistakes in twelve hours. If they started selling that capability, what would happen?

If it’s cheap enough, you might wonder if professors would choose to use the OpenAI model instead of hiring students. I don’t think this would happen, though: I think it misunderstands why these kinds of student projects exist in a theoretical field. Professors sometimes use students to get results they care about, but more often, the student’s interest is itself the motivation, with the professor wanting to educate someone, to empire-build, or just to take on their share of the department’s responsibilities. AI is only useful for this insofar as AI companies continue reaching out to these people to generate press releases: once this is routinely possible, the motivation goes away.

More dangerously, if it’s even cheaper, you could imagine students being tempted to use it. The whole point of a student project is to train and acculturate the student, to get them to the point where they have affection for the field and the capability to do more impressive things. You can’t skip that, but people are going to be tempted to.

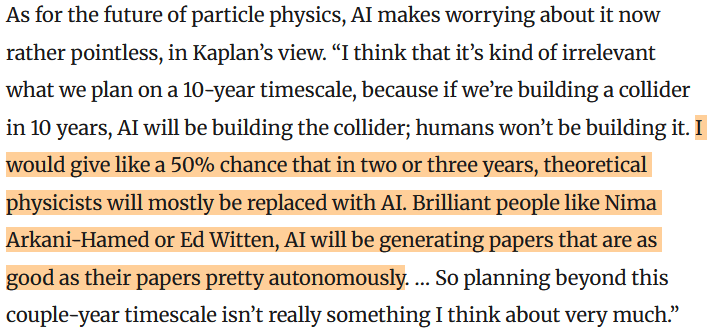

And of course, there is the broader question of how much farther this technology can go. That’s the hardest to estimate here, since we don’t know the prompts used. So I don’t know if seeing this result tells us anything more about the bigger picture than we knew going in.

Remaining questions:

At the end of the day, there are a lot of things I still want to know. And if I do end up covering this professionally, they’re things I’ll ask.

- What was the prompt given to the internal model, and how much did it do based on that prompt?

- Was it really done in one shot, no retries or feedback?

- How much did running the internal model cost?

- Is this result likely to be useful? Are there things people want to calculate that this could make easier? Recursion relations it could seed? Is it useful for SCET somehow?

- How easy would it have been for the authors to do what the LLM did? What about other experts in the community?