A commenter recently asked me about the different “tribes” in my sub-field. I’ve been working in an area called “amplitudeology”, where we try to find more efficient ways to make predictions (calculate “scattering amplitudes”) for particle physics and gravitational waves. I plan to do a longer post on the “tribes” of amplitudeology…but not this week.

This week, I’ve got a simpler goal. I want to talk about where these kinds of “tribes” come from, in general. A sub-field is a group of researchers focused on a particular idea, or a particular goal. How do those groups change over time? How do new sub-groups form? For the amplitudes fans in the audience, I’ll use amplitudeology examples to illustrate.

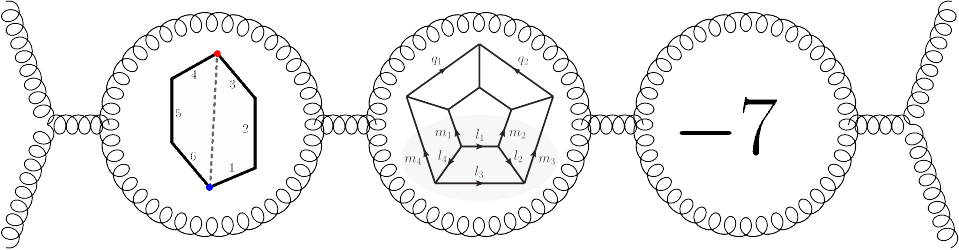

The first way subfields gain new tribes is by differentiation. Do a PhD or a Postdoc with someone in a subfield, and you’ll learn that subfield’s techniques. That’s valuable, but probably not enough to get you hired: if you’re just a copy of your advisor, then the field just needs your advisor: research doesn’t need to be done twice. You need to differentiate yourself, finding a variant of what your advisor does where you can excel. The most distinct such variants go on to form distinct tribes of their own. This can also happen for researchers at the same level who collaborate as Postdocs. Each has to show something new, beyond what they did as a team. In my sub-field, it’s the source of some of the bigger tribes. Lance Dixon, Zvi Bern, and David Kosower made their names working together, but when they found long-term positions they made new tribes of their own. Zvi Bern focused on supergravity, and later on gravitational waves, while Lance Dixon was a central figure in the symbology bootstrap.

(Of course, if you differentiate too far you end up in a different sub-field, or a different field altogether. Jared Kaplan was an amplitudeologist, but I wouldn’t call Anthropic an amplitudeology project, although it would help my job prospects if it was!)

The second way subfields gain new tribes is by bridges. Sometimes, a researcher in a sub-field needs to collaborate with someone outside of that sub-field. These collaborations can just be one-and-done, but sometimes they strike up a spark, and people in each sub-field start realizing they have a lot more in common than they realized. They start showing up to each other’s conferences, and eventually identifying as two tribes in a single sub-field. An example from amplitudeology is the group founded by Dirk Kreimer, with a long track record of interesting work on the boundary between math and physics. They didn’t start out interacting with the “amplitudeology” community itself, but over time they collaborated with them more and more, and now I think it’s fair to say they’re a central part of the sub-field.

A third way subfields gain new tribes is through newcomers. Sometimes, someone outside of a subfield will decide they have something to contribute. They’ll read up on the latest papers, learn the subfield’s techniques, and do something new with them: applying them to a new problem of their own interest, or applying their own methods to a problem in the subfield. Because these people bring something new, either in what they work on or how they do it, they often spin off new tribes. Many new tribes in amplitudeology have come from this process, from Edward Witten’s work on the twistor string bringing in twistor approaches to Nima Arkani-Hamed’s idiosyncratic goals and methods.

There are probably other ways subfields gain new tribes, but these are the ones I came up with. If you think of more, let me know in the comments!