On this blog, I write about particle physics for the general public. I try to make things as simple as possible, but I do have to assume some things. In particular, I usually assume you know what particles are!

This time, I won’t do that. I know some people out there don’t know what a particle is, or what particle physicists do. If you’re a person like that, this post is for you! I’m going to give a gentle introduction to what particle physics is all about.

Let’s start with atoms.

Every object and substance around you, everything you can touch or lift or walk on, the water you drink and the air you breathe, all of these are made up of atoms. Some are simple: an iron bar is made of Iron atoms, aluminum foil is mostly Aluminum atoms. Some are made of combinations of atoms into molecules, like water’s famous H2O: each molecule has two Hydrogen atoms and one Oxygen atom. Some are made of more complicated mixtures: air is mostly pairs of Nitrogen atoms, with a healthy amount of pairs of Oxygen, some Carbon Dioxide (CO2), and many other things, while the concrete sidewalks you walk on have Calcium, Silicon, Aluminum, Iron, and Oxygen, all combined in various ways.

There is a dizzying array of different types of atoms, called chemical elements. Most occur in nature, but some are man-made, created by cutting-edge nuclear physics. They can all be organized in the periodic table of elements, which you’ve probably seen on a classroom wall.

The periodic table is called the periodic table because it repeats, periodically. Each element is different, but their properties resemble each other. Oxygen is a gas, Sulfur a yellow powder, Polonium an extremely radioactive metal…but just as you can find H2O, you can make H2S, and even H2Po. The elements get heavier as you go down the table, and more metal-like, but their chemical properties, the kinds of molecules you can make with them, repeat.

Around 1900, physicists started figuring out why the elements repeat. What they discovered is that each atom is made of smaller building-blocks, called sub-atomic particles. (“Sub-atomic” because they’re smaller than atoms!) Each atom has electrons on the outside, and on the inside has a nucleus made of protons and neutrons. Atoms of different elements have different numbers of protons and electrons, which explains their different properties.

Around the same time, other physicists studied electricity, magnetism, and light. These things aren’t made up of atoms, but it was discovered that they are all aspects of the same force, the electromagnetic force. And starting with Einstein, physicists figured out that this force has particles too. A beam of light is made up of another type of sub-atomic particle, called a photon.

For a little while then, it seemed that the universe was beautifully simple. All of matter was made of electrons, protons, and neutrons, while light was made of photons.

(There’s also gravity, of course. That’s more complicated, in this post I’ll leave it out.)

Soon, though, nuclear physicists started noticing stranger things. In the 1930’s, as they tried to understand the physics behind radioactivity and mapped out rays from outer space, they found particles that didn’t fit the recipe. Over the next forty years, theoretical physicists puzzled over their equations, while experimental physicists built machines to slam protons and electrons together, all trying to figure out how they work.

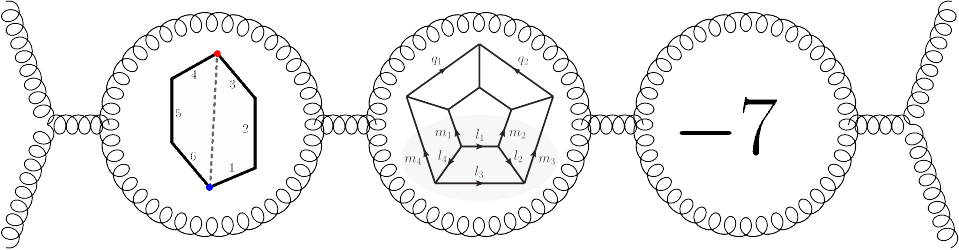

Finally, in the 1970’s, physicists had a theory they thought they could trust. They called this theory the Standard Model. It organized their discoveries, and gave them equations that could predict what future experiments would see.

In the Standard Model, there are two new forces, the weak nuclear force and the strong nuclear force. Just like photons for the electromagnetic force, each of these new forces has a particle. The general word for these particles is bosons, named after Satyendra Nath Bose, a collaborator of Einstein who figured out the right equations for this type of particle. The weak force has bosons called W and Z, while the strong force has bosons called gluons. A final type of boson, called the Higgs boson after a theorist who suggested it, rounds out the picture.

The Standard Model also has new types of matter particles. Neutrinos interact with the weak nuclear force, and are so light and hard to catch that they pass through nearly everything. Quarks are inside protons and neutrons: a proton contains one one down quark and two up quarks, while a neutron contains two down quarks and one up quark. The quarks explained all of the other strange particles found in nuclear physics.

Finally, the Standard Model, like the periodic table, repeats. There are three generations of particles. The first, with electrons, up quarks, down quarks, and one type of neutrino, show up in ordinary matter. The other generations are heavier, and not usually found in nature except in extreme conditions. The second generation has muons (similar to electrons), strange quarks, charm quarks, and a new type of neutrino called a muon-neutrino. The third generation has tauons, bottom quarks, top quarks, and tau-neutrinos.

(You can call these last quarks “truth quarks” and “beauty quarks” instead, if you like.)

Physicists had the equations, but the equations still had some unknowns. They didn’t know how heavy the new particles were, for example. Finding those unknowns took more experiments, over the next forty years. Finally, in 2012, the last unknown was found when a massive machine called the Large Hadron Collider was used to measure the Higgs boson.

We think that these particles are all elementary particles. Unlike protons and neutrons, which are both made of up quarks and down quarks, we think that the particles of the Standard Model are not made up of anything else, that they really are elementary building-blocks of the universe.

We have the equations, and we’ve found all the unknowns, but there is still more to discover. We haven’t seen everything the Standard Model can do: to see some properties of the particles and check they match, we’d need a new machine, one even bigger than the Large Hadron Collider. We also know that the Standard Model is incomplete. There is at least one new particle, called dark matter, that can’t be any of the known particles. Mysteries involving the neutrinos imply another type of unknown particle. We’re also missing deeper things. There are patterns in the table, like the generations, that we can’t explain.

We don’t know if any one experiment will work, or if any one theory will prove true. So particle physicists keep working, trying to find new tricks and make new discoveries.