I was at a Zoomference last week, called QCD Meets Gravity, about the many ways gravity can be thought of as the “square” of other fundamental forces. I didn’t have time to write much about the actual content of the conference, so I figured I’d say a bit more this week.

A big theme of this conference, as in the past few years, was gravitational waves. From LIGO’s first announcement of a successful detection, amplitudeologists have been developing new methods to make predictions for gravitational waves more efficient. It’s a field I’ve dabbled in a bit myself. Last year’s QCD Meets Gravity left me impressed by how much progress had been made, with amplitudeologists already solidly part of the conversation and able to produce competitive results. This year felt like another milestone, in that the amplitudeologists weren’t just catching up with other gravitational wave researchers on the same kinds of problems. Instead, they found new questions that amplitudes are especially well-suited to answer. These included combining two pieces of these calculations (“potential” and “radiation”) that the older community typically has to calculate separately, using an old quantum field theory trick, finding the gravitational wave directly from amplitudes, and finding a few nice calculations that can be used to “generate” the rest.

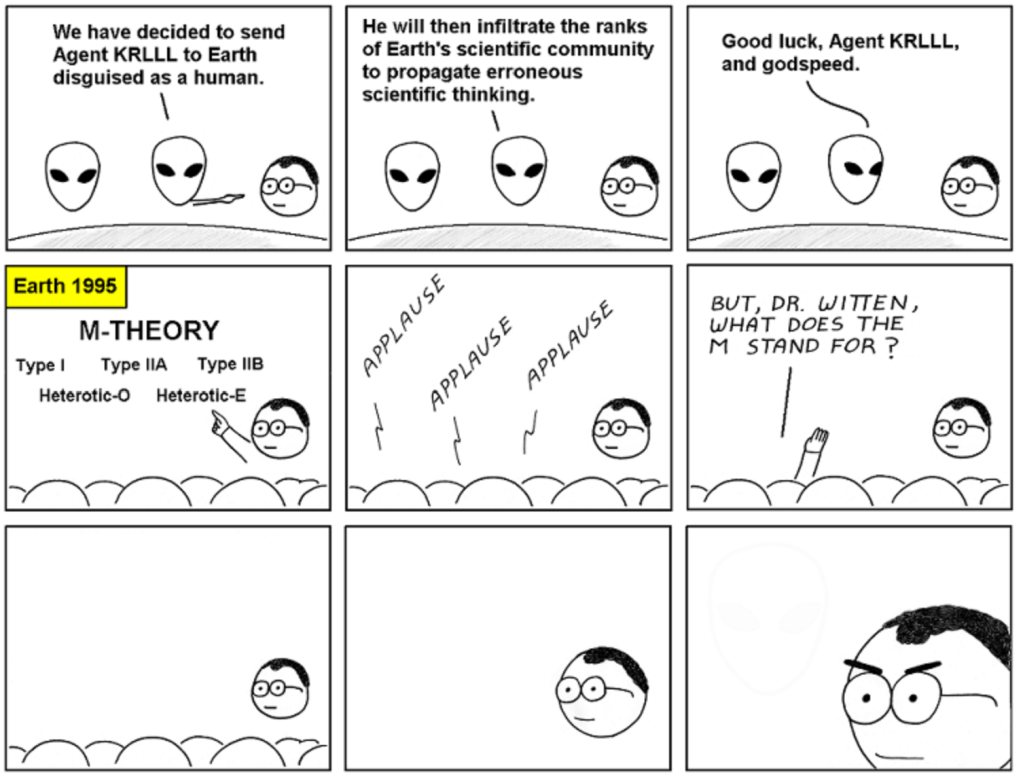

A large chunk of the talks focused on different “squaring” tricks (or as we actually call them, double-copies). There were double-copies for cosmology and conformal field theory, for the celestial sphere, and even some version of M theory. There were new perspectives on the double-copy, new building blocks and algebraic structures that lie behind it. There were talks on the so-called classical double-copy for space-times, where there have been some strange discoveries (an extra dimension made an appearance) but also a more rigorous picture of where the whole thing comes from, using twistor space. There were not one, but two talks linking the double-copy to the Navier-Stokes equation describing fluids, from two different groups. (I’m really curious whether these perspectives are actually useful for practical calculations about fluids, or just fun to think about.) Finally, while there wasn’t a talk scheduled on this paper, the authors were roped in by popular demand to talk about their work. They claim to have made progress on a longstanding puzzle, how to show that double-copy works at the level of the Lagrangian, and the community was eager to dig into the details.

From there, a grab-bag of talks covered other advancements. There were talks from string theorists and ambitwistor string theorists, from Effective Field Theorists working on gravity and the Standard Model, from calculations in N=4 super Yang-Mills, QCD, and scalar theories. Simon Caron-Huot delved into how causality constrains the theories we can write down, showing an interesting case where the common assumption that all parameters are close to one is actually justified. Nima Arkani-Hamed began his talk by saying he’d surprise us, which he certainly did (and not by keeping on time). It’s tricky to explain why his talk was exciting. Comparing to his earlier discovery of the Amplituhedron, which worked for a toy model, this is a toy calculation in a toy model. While the Amplituhedron wasn’t based on Feynman diagrams, this can’t even be compared with Feynman diagrams. Instead of expanding in a small coupling constant, this expands in a parameter that by all rights should be equal to one. And instead of positivity conditions, there are negativity conditions. All I can say is that with all of that in mind, it looks like real progress on an important and difficult problem from a totally unanticipated direction. In a speech summing up the conference, Zvi Bern mentioned a few exciting words from Nima’s talk: “nonplanar”, “integrated”, “nonperturbative”. I’d add “differential equations” and “infinite sums of ladder diagrams”. Nima and collaborators are trying to figure out what happens when you sum up all of the Feynman diagrams in a theory. I’ve made progress in the past for diagrams with one “direction”, a ladder that grows as you add more loops, but I didn’t know how to add “another direction” to the ladder. In very rough terms, Nima and collaborators figured out how to add that direction.

I’ve probably left things out here, it was a packed conference! It’s been really fun seeing what the community has cooked up, and I can’t wait to see what happens next.