Before I launch into the post: I got interviewed on Theoretically Podcasting, a new YouTube channel focused on beginning grad student-level explanations of topics in theoretical physics. If that sounds interesting to you, check it out!

This Fall is paper season for me. I’m finishing up a number of different projects, on a number of different things. Each one was its own puzzle: a curious object found, polished, and sent off into the world.

Monday I published the first of these curiosities, along with Jake Bourjaily and Cristian Vergu.

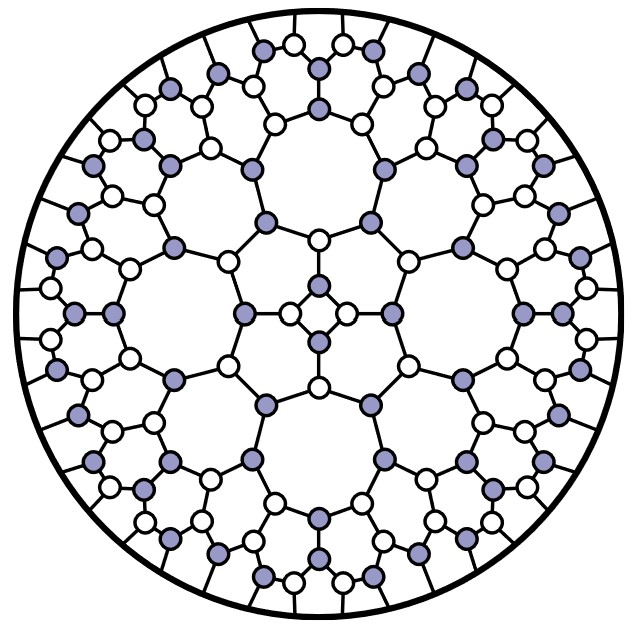

I’ve mentioned before that the calculations I do involve a kind of “alphabet“. Break down a formula for the probability that two particles collide, and you find pieces that occur again and again. In the nicest cases, those pieces are rational functions, but they can easily get more complicated. I’ve talked before about a case where square roots enter the game, for example. But if square roots appear, what about something even more complicated? What about cubic roots?

Occasionally, my co-authors and I would say something like that at the end of a talk and an older professor would scoff: “Cube roots? Impossible!”

You might imagine these professors were just being unreasonable skeptics, the elderly-but-distinguished scientists from that Arthur C. Clarke quote. But while they turned out to be wrong, they weren’t being unreasonable. They were thinking back to theorems from the 60’s, theorems which seemed to argue that these particle physics calculations could only have a few specific kinds of behavior: they could behave like rational functions, like logarithms, or like square roots. Theorems which, as they understood them, would have made our claims impossible.

Eventually, we decided to figure out what the heck was going on here. We grabbed the simplest example we could find (a cube root involving three loops and eleven gluons in N=4 super Yang-Mills…yeah) and buckled down to do the calculation.

When we want to calculate something specific to our field, we can reference textbooks and papers, and draw on our own experience. Much of the calculation was like that. A crucial piece, though, involved something quite a bit less specific: calculating a cubic root. And for things like that, you can tell your teachers we use only the very best: Wikipedia.

Check out the Wikipedia entry for the cubic formula. It’s complicated, in ways the quadratic formula isn’t. It involves complex numbers, for one. But it’s not that crazy.

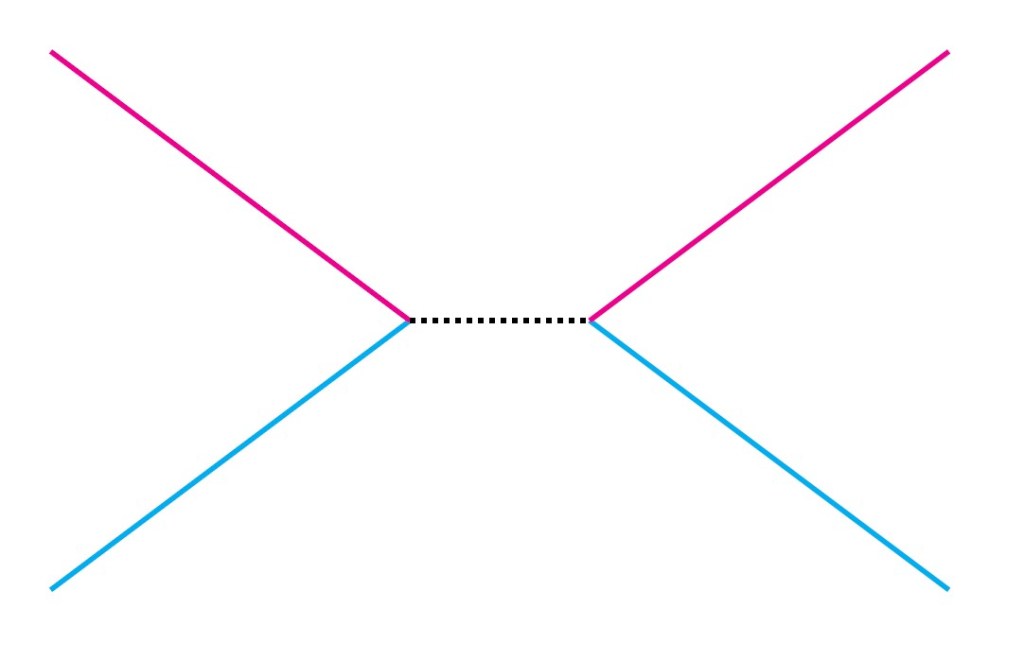

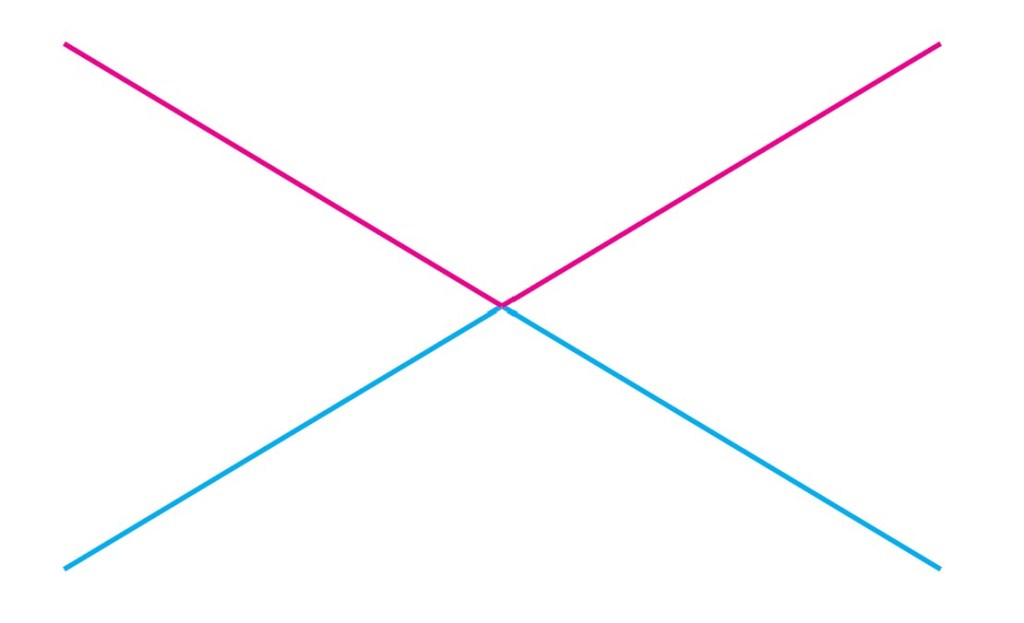

What those theorems from the 60’s said (and what they actually said, not what people misremembered them as saying), was that you can’t take a single limit of a particle physics calculation, and have it behave like a cubic root. You need to take more limits, not just one, to see it.

It turns out, you can even see this just from the Wikipedia entry. There’s a big cube root sign in the middle there, equal to some variable “C”. Look at what’s inside that cube root. You want that part inside to vanish. That means two things need to cancel: Wikipedia labels them , and

. Do some algebra, and you’ll see that for those to cancel, you need

.

So you look at the limit, . This time you need not just some algebra, but some calculus. I’ll let the students in the audience work it out, but at the end of the day, you should notice how C behaves when

is small. It isn’t like

. It’s like just plain

. The cube root goes away.

It can come back, but only if you take another limit: not just , but

as well. And that’s just fine according to those theorems from the 60’s. So our cubic curiosity isn’t impossible after all.

Our calculation wasn’t quite this simple, of course. We had to close a few loopholes, checking our example in detail using more than just Wikipedia-based methods. We found what we thought was a toy example, that turned out to be even more complicated, involving roots of a degree-six polynomial (one that has no “formula”!).

And in the end, polished and in their display case, we’ve put our examples up for the world to see. Let’s see what people think of them!