Nima Arkani-Hamed shows up surprisingly rarely in popular science books. A major figure in my former field, Nima is extremely quotable (frequent examples include “spacetime is doomed” and “the universe is not a crappy metal”), but those quotes don’t seem to quite have reached the popular physics mainstream. He’s been interviewed in books by physicists, and has a major role in one popular physics book that I’m aware of. From this scattering of mentions, I was quite surprised to hear of another book where he makes an appearance: not a popular physics book at all, but a popular psychology book: Donald Hoffman’s The Case Against Reality. Naturally, this meant I had to read it.

Then, I saw the first quote on the back cover…or specifically, who was quoted.

Seeing that, I settled in for a frustrating read.

A few pages later, I realized that this, despite his endorsement, is not a Deepak Chopra kind of book. Hoffman is careful in some valuable ways. Specifically, he has a philosopher’s care, bringing up objections and potential holes in his arguments. As a result, the book wasn’t frustrating in the way I expected.

It was even more frustrating, actually. But in an entirely different way.

When a science professor writes a popular book, the result is often a kind of ungainly Frankenstein. The arguments we want to make tend to be better-suited to shorter pieces, like academic papers, editorials, and blog posts. To make these into a book, we have to pad them out. We stir together all the vaguely related work we’ve done, plus all the best-known examples from other peoples’ work, trying (often not all that hard) to make the whole sound like a cohesive story. Read enough examples, and you start to see the joints between the parts.

Hoffman is ostensibly trying to tell a single story. His argument is that the reality we observe, of objects in space and time, is not the true reality. It is a convenient reality, one that has led to our survival, but evolution has not (and as he argues, cannot) let us perceive the truth. Instead, he argues that the true reality is consciousness: a world made up of conscious beings interacting with each other, with space, time, and all the rest emerging as properties of those interactions.

That certainly sounds like it could be one, cohesive argument. In practice, though, it is three, and they don’t fit together as well as he’d hope.

Hoffman is trained as a psychologist. As such, one of the arguments is psychological: that research shows that we mis-perceive the world in service of evolutionary fitness.

Hoffman is a cognitive scientist, and while many cognitive scientists are trained as psychologists, others are trained as philosophers. As such, one of his arguments is philosophical: that the contents of consciousness can never be explained by relations between material objects, and that evolution, and even science, systematically lead us astray.

Finally, Hoffman has evidently been listening to and reading the work of some physicists, like Nima and Carlo Rovelli. As such, one of his arguments is physical: that physicists believe that space and time are illusions and that consciousness may be fundamental, and that the conclusions of the book lead to his own model of the basic physical constituents of the world.

The book alternates between these three arguments, so rather than in chapter order, I thought it would be better to discuss each argument in its own section.

The Psychological Argument

Sometimes, when two academics get into a debate, they disagree about what’s true. Two scientists might argue about whether an experiment was genuine, whether the statistics back up a conclusion, or whether a speculative theory is actually consistent. These are valuable debates, and worth reading about if you want to learn something about the nature of reality.

Sometimes, though, two debating academics agree on what’s true, and just disagree on what’s important. These debates are, at best, relevant to other academics and funders. They are not generally worth reading for anybody else, and are often extremely petty and dumb.

Hoffman’s psychological argument, regrettably, is of the latter kind. He would like to claim it’s the former, and to do so he marshals a host of quotes from respected scientists that claim that human perception is veridical: that what we perceive is real, courtesy of an evolutionary process that would have killed us off if it wasn’t. From that perspective, every psychological example Hoffman gives is a piece of counter-evidence, a situation where evolution doesn’t just fail to show us the true nature of reality, but actively hides reality from us.

The problem is that, if you actually read the people Hoffman quotes, they’re clearly not making the extreme point he claims. These people are psychologists, and all they are arguing is that perception is veridical in a particular, limited way. They argue that we humans are good at estimating distances or positions of objects, or that we can see a wide range of colors. They aren’t making some sort of philosophical point about those distances or positions or colors being how the world “really is”, nor are they claiming that evolution never makes humans mis-perceive.

Instead, they, and thus Hoffman, are arguing about importance. When studying humans, is it more useful to think of us as perceiving the world as it is? Or is it more useful to think of evolution as tricking us? Which happens more often?

The answers to each of those questions have to be “it depends”. Neither answer can be right all the time. At most then, this kind of argument can convince one academic to switch from researching in one way to researching in another, by saying that right now one approach is a better strategy. It can’t tell us anything more.

If the argument Hoffman is trying to get across here doesn’t matter, are there other reasons to read this part?

Popular psychology books tend to re-use a few common examples. There are some good ones, so if you haven’t read such a book you probably should read a couple, just to hear about them. For example, Hoffman tells the story of the split-brain patients, which is definitely worth being aware of.

(Those of you who’ve heard that story may be wondering how the heck Hoffman squares it with his idea of consciousness as fundamental. He actually does have a (weird) way to handle this, so read on.)

The other examples come from Hoffman’s research, and other research in his sub-field. There are stories about what optical illusions tell us about our perception, about how evolution primes us to see different things as attractive, and about how advertisers can work with attention.

These stories would at least be a source of a few more cool facts, but I’m a bit wary. The elephant in the room here is the replication crisis. Paper after paper in psychology has turned out to be a statistical mirage, accidental successes that fail to replicate in later experiments. This can happen without any deceit on the part of the psychologist, it’s just a feature of how statistics are typically done in the field.

Some psychologists make a big deal about the replication crisis: they talk about the statistical methods they use, and what they do to make sure they’re getting a real result. Hoffman talks a bit about tricks to rule out other explanations, but mostly doesn’t focus on this kind of thing.. This doesn’t mean he’s doing anything wrong: it might just be it’s off-topic. But it makes it a bit harder to trust him, compared to other psychologists who do make a big deal about it.

The Philosophical Argument

Hoffman structures his book around two philosophical arguments, one that appears near the beginning and another that, as he presents it, is the core thesis of the book. He calls both of these arguments theorems, a naming choice sure to irritate mathematicians and philosophers alike, but the mathematical content in either is for the most part not the point: in each case, the philosophical setup is where the arguments get most of their strength.

The first of these arguments, called The Scrambling Theorem, is set up largely as background material: not his core argument, but just an entry into the overall point he’s making. I found it helpful as a way to get at his reasoning style, the sorts of things he cares about philosophically and the ones he doesn’t.

The Scrambling Theorem is meant to weigh in on the debate over a thought experiment called the Inverted Spectrum, which in turn weighs on the philosophical concept of qualia. The Inverted Spectrum asks us to imagine someone who sees the spectrum of light inverted compared to how we see it, so that green becomes red and red becomes green, without anything different about their body or brain. Such a person would learn to refer to colors the same ways that we do, still referring to red blood even though they see what we see when we see green grass. Philosophers argue that, because we can imagine this, the “qualia” we see in color, like red or green, are distinct from their practical role: they are images in the mind’s eye that can be compared across minds, but do not correspond to anything we have yet characterized scientifically in the physical world.

As a response, other philosophers argued that you can’t actually invert the spectrum. Colors aren’t really a wheel, we can distinguish, for example, more colors between red and blue than between green and yellow. Just flipping colors around would have detectable differences that would have to have physical implications, you can’t just swap qualia and nothing else.

The Scrambling Theorem is in response to this argument. Hoffman argues that, while you can’t invert the spectrum, you can scramble it. By swapping not only the colors, but the relations between them, you can arrange any arbitrary set of colors however else you’d like. You can declare that green not only corresponds to blood and not grass, but that it has more colors between it and yellow, perhaps by stealing them from the other side of the color wheel. If you’re already allowed to swap colors and their associations around, surely you can do this too, and change order and distances between them.

Believe it or not, I think Hoffman’s argument is correct, at least in its original purpose. You can’t respond to the Inverted Spectrum just by saying that colors are distributed differently on different sides of the color wheel. If you want to argue against the Inverted Spectrum, you need a better argument.

Hoffman’s work happens to suggest that better argument. Because he frames this argument in the language of mathematics, as a “theorem”, Hoffman’s argument is much more general than the summary I gave above. He is arguing that not merely can you scramble colors, but anything you like. If you want to swap electrons and photons, you can: just make your photons interact with everything the way electrons did, and vice versa. As long as you agree that the things you are swapping exist, according to Hoffman, you are free to exchange them and their properties any way you’d like.

This is because, to Hoffman, things that “actually exist” cannot be defined just in terms of their relations. An electron is not merely a thing that repels other electrons and is attracted to protons and so on, it is a thing that “actually exists” out there in the world. (Or, as he will argue, it isn’t really. But that’s because in the end he doesn’t think electrons exist.)

(I’m tempted to argue against this with a mathematical object like group elements. Surely the identity element of a group is defined by its relations? But I think he would argue identity elements of groups don’t actually exist.)

In the end, Hoffman is coming from a particular philosophical perspective, one common in modern philosophers of metaphysics, the study of the nature of reality. From this perspective, certain things exist, and are themselves by necessity. We cannot ask what if a thing were not itself. For example, in this perspective it is nonsense to ask what if Superman was not Clark Kent, because the two names refer to the same actually existing person.

(If, you know, Superman actually existed.)

Despite the name of the book, Hoffman is not actually making a case against reality in general. He very much seems to believe in this type of reality, in the idea that there are certain things out there that are real, independent of any purely mathematical definition of their properties. He thinks they are different things than you think they are, but he definitely thinks there are some such things, and that it’s important and scientifically useful to find them.

Hoffman’s second argument is, as he presents it, the core of the book. It’s the argument that’s supposed to show that the world is almost certainly not how we perceive it, even through scientific instruments and the scientific method. Once again, he calls it a theorem: the Fitness Beats Truth theorem.

The Fitness Beats Truth argument begins with a question: why should we believe what we see? Why do we expect that the things we perceive should be true?

In Hoffman’s mind, the only answer is evolution. If we perceived the world inaccurately, we would die out, replaced by creatures that perceived the world better than we did. You might think we also have evidence from biology, chemistry, and physics: we can examine our eyes, test them against cameras, see how they work and what they can and can’t do. But to Hoffman, all of this evidence may be mistaken, because to learn biology, chemistry, and physics we must first trust that we perceive the world correctly to begin with. Evolution, though, doesn’t rely on any of that. Even if we aren’t really bundles of cells replicating through DNA and RNA, we should still expect something like evolution, some process by which things differ, are selected, and reproduce their traits differently in the next generation. Such things are common enough, and general enough, that one can (handwavily) expect them through pure reason alone.

But, says Hoffman’s psychology experience, evolution tricks us! We do mis-perceive, and systematically, in ways that favor our fitness over reality. And so Hoffman asks, how often should we expect this to happen?

The Fitness Beats Truth argument thinks of fitness as randomly distributed: some parts of reality historically made us more fit, some less. This distribution could match reality exactly, so that for any two things that are actually different, they will make us fit in different ways. But it doesn’t have to. There might easily be things that are really very different from each other, but which are close enough from a fitness perspective that to us they seem exactly the same.

The “theorem” part of the argument is an attempt to quantify this. Hoffman imagines a pixelated world, and asks how likely it is that a random distribution of fitness matches a random distribution of pixels. This gets extremely unlikely for a world of any reasonable size, for pretty obvious reasons. Thus, Hoffman concludes: in a world with evolution, we should almost always expect it to hide something from us. The world, if it has any complexity at all, has an almost negligible probability of being as we perceive it.

On one level, this is all kind of obvious. Evolution does trick us sometimes, just as it tricks other animals. But Hoffman is trying to push this quite far, to say that ultimately our whole picture of reality, not just our eyes and ears and nose but everything we see with microscopes and telescopes and calorimeters and scintillators, all of that might be utterly dramatically wrong. Indeed, we should expect it to be.

In this house, we tend to dismiss the Cartesian Demon. If you have an argument that makes you doubt literally everything, then it seems very unlikely you’ll get anything useful from it. Unlike Descartes’s Demon, Hoffman thinks we won’t be tricked forever. The tricks evolution plays on us mattered in our ancestral environment, but over time we move to stranger and stranger situations. Eventually, our fitness will depend on something new, and we’ll need to learn something new about reality.

This means that ultimately, despite the skeptical cast, Hoffman’s argument fits with the way science already works. We are, very much, trying to put ourselves in new situations and test whether our evolved expectations still serve us well or whether we need to perceive things anew. That is precisely what we in science are always doing, every day. And as we’ll see in the next section, whatever new things we have to learn have no particular reason to be what Hoffman thinks they should be.

But while it doesn’t really matter, I do still want to make one counter-argument to Fitness Beats Truth. Hoffman considers a random distribution of fitness, and asks what the chance is that it matches truth. But fitness isn’t independent of truth, and we know that not just from our perception, but from deeper truths of physics and mathematics. Fitness is correlated with truth, fitness often matches truth, for one key reason: complex things are harder than simple things.

Imagine a creature evolving an eye. They have a reason, based on fitness, to need to know where their prey is moving. If evolution was a magic wand, and chemistry trivial, it would let them see their prey, and nothing else. But evolution is not magic, and chemistry is not trivial. The easiest thing for this creature to see is patches of light and darkness. There are many molecules that detect light, because light is a basic part of the physical world. To detect just prey, you need something much more complicated, molecules and cells and neurons. Fitness imposes a cost, and it means that the first eyes that evolve are spots, detecting just light and darkness.

Hoffman asks us not to assume that we know how eyes work, that we know how chemistry works, because we got that knowledge from our perceptions. But the nature of complexity and simplicity, entropy and thermodynamics and information, these are things we can approach through pure thought, as much as evolution. And those principles tell us that it will always be easier for an organism to perceive the world as it truly is than not, because the world is most likely simple and it is most likely the simplest path to perceive it directly. When benefits get high enough, when fitness gets strong enough, we can of course perceive the wrong thing. But if there is only a small fitness benefit to perceiving something incorrectly, then simplicity will win out. And by asking simpler and simpler questions, we can make real durable scientific progress towards truth.

The Physical Argument

So if I’m not impressed by the psychology or the philosophy, what about the part that motivated me to read the book in the first place, the physics?

Because this is, in a weird and perhaps crackpot way, a physics book. Hoffman has a specific idea, more specific than just that the world we perceive is an evolutionary illusion, more specific than that consciousness cannot be explained by the relations between physical particles. He has a proposal, based on these ideas, one that he thinks might lead to a revolutionary new theory of physics. And he tries to argue that physicists, in their own way, have been inching closer and closer to his proposal’s core ideas.

Hoffman’s idea is that the world is made, not of particles or fields or anything like that, but of conscious agents. You and I are, in this picture, certainly conscious agents, but so are the sources of everything we perceive. When we reach out and feel a table, when we look up and see the Sun, those are the actions of some conscious agent intruding on our perceptions. Unlike panpsychists, who believe that everything in the world is conscious, Hoffman doesn’t believe that the Sun itself is conscious, or is made of conscious things. Rather, he thinks that the Sun is an evolutionary illusion that rearranges our perceptions in a convenient way. The perceptions still come from some conscious thing or set of conscious things, but unlike in panpsychism they don’t live in the center of our solar system, or in any other place (space and time also being evolutionary illusions in this picture). Instead, they could come from something radically different that we haven’t imagined yet.

Earlier, I mentioned split brain patients. For anyone who thinks of conscious beings as fundamental, split brain patients are a challenge. These are people who, as a treatment for epilepsy, had the bridge between the two halves of their brain severed. The result is eerily as if their consciousness was split in two. While they only express one train of thought, that train of thought seems to only correspond to the thoughts of one side of their brain, controlling only half their body. The other side, controlling the other half of their body, appears to have different thoughts, different perceptions, and even different opinions, which are made manifest when instead of speaking they use that side of their body to gesture and communicate. While some argue that these cases are over-interpreted and don’t really show what they’re claimed to, Hoffman doesn’t. He accepts that these split-brain patients genuinely have their consciousness split in two.

Hoffman thinks this isn’t a problem because for him, conscious agents can be made up of other conscious agents. Each of us is conscious, but we are also supposed to be made up of simpler conscious agents. Our perceptions and decisions are not inexplicable, but can be explained in terms of the interactions of the simpler conscious entities that make us up, each one communicating with the others.

Hoffman speculates that everything is ultimately composed of the simplest possible conscious agents. For him, a conscious agent must do two things: perceive, and act. So the simplest possible agent perceives and acts in the simplest possible way. They perceive a single bit of information: 0 or 1, true or false, yes or no. And they take one action, communicating a different bit of information to another conscious agent: again, 0 or 1, true or false, yes or no.

Hoffman thinks that this could be the key to a new theory of physics. Instead of thinking about the world as composed of particles and fields, think about it as composed of these simple conscious agents, each one perceiving and communicating one bit at a time.

Hoffman thinks this, in part, because he sees physics as already going in this direction. He’s heard that “spacetime is doomed”, he’s heard that quantum mechanics is contextual and has no local realism, he’s heard that quantum gravity researchers think the world might be a hologram and space-time has a finite number of bits. This all “rhymes” enough with his proposal that he’s confident physics has his back.

Hoffman is trained in psychology. He seems to know his philosophy, at least enough to engage with the literature there. But he is absolutely not a physicist, and it shows. Time and again it seems like he relies on “pop physics” accounts that superficially match his ideas without really understanding what the physicists are actually talking about.

He keeps up best when it comes to interpretations of quantum mechanics, a field where concepts from philosophy play a meaningful role. He covers the reasons why quantum mechanics keeps philosophers up at night: Bell’s Theorem, which shows that a theory that matches the predictions of quantum mechanics cannot both be “realist”, with measurements uncovering pre-existing facts about the world, and “local”, with things only influencing each other at less than the speed of light, the broader notion of contextuality, where measured results are dependent on which other measurements are made, and the various experiments showing that both of these properties hold in the real world.

These two facts, and their implications, have spawned a whole industry of interpretations of quantum mechanics, where physicists and philosophers decide which side of various dilemmas to take and how to describe the results. Hoffman quotes a few different “non-realist” interpretations: Carlo Rovelli’s Relational Quantum Mechanics, Quantum Bayesianism/QBism, Consistent Histories, and whatever Chris Fields is into. These are all different from one another, which Hoffman is aware of. He just wants to make the case that non-realist interpretations are reasonable, that the physicists collectively are saying “maybe reality doesn’t exist” just like he is.

The problem is that Hoffman’s proposal is not, in the quantum mechanics sense, non-realist. Yes, Hoffman thinks that the things we observe are just an “interface”, that reality is really a network of conscious agents. But in order to have a non-realist interpretation, you need to also have other conscious agents not be real. That’s easily seen from the old “Wigner’s friend” thought experiment, where you put one of your friends in a Schrodinger’s cat-style box. Just as Schrodinger’s cat can be both alive and dead, your friend can both have observed something and not have observed it, or observed something and observed something else. The state of your friend’s mind, just like everything else in a non-realist interpretation, doesn’t have a definite value until you measure it.

Hoffman’s setup doesn’t, and can’t, work that way. His whole philosophical project is to declare that certain things exist and others don’t: the sun doesn’t exist, conscious agents do. In a non-realist interpretation, the sun and other conscious agents can both be useful descriptions, but ultimately nothing “really exists”. Science isn’t a catalogue of what does or doesn’t “really exist”, it’s a tool to make predictions about your observations.

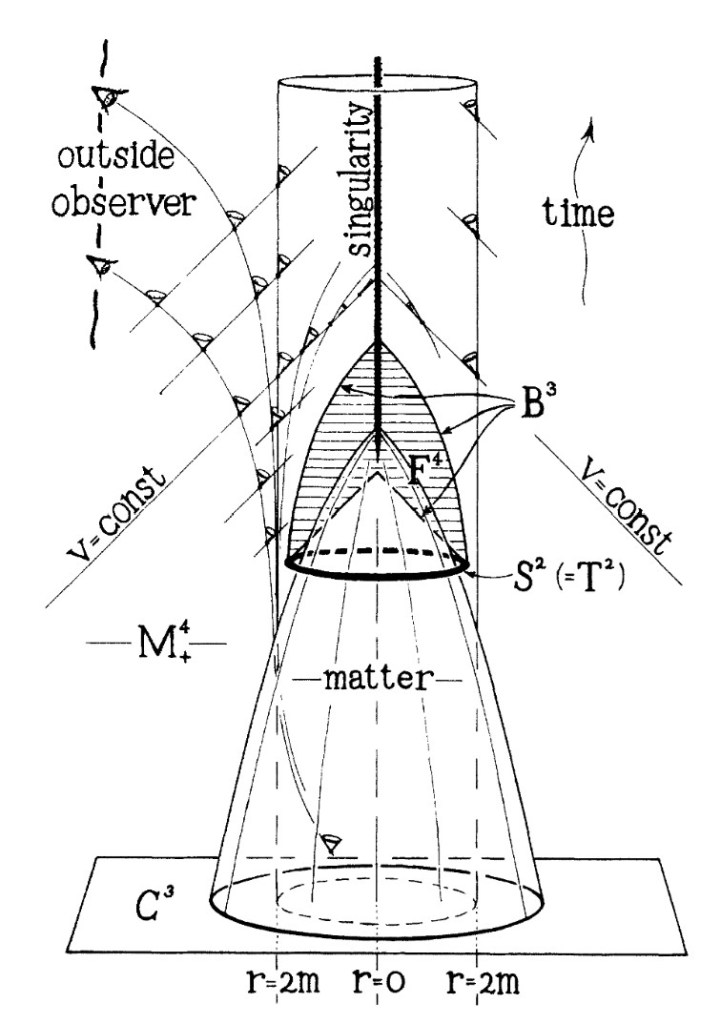

Hoffman gets even more confused when he gets to quantum gravity. He starts out with a common misconception: that the Planck length represents the “pixels” of reality, sort of like the pixels of your computer screen, which he uses to support his “interface” theory of consciousness. This isn’t really the right way to think about it the Planck length, though, and certainly isn’t what the people he’s quoting have in mind. The Planck length is a minimum scale in that space and time stop making sense as one approaches it, but that’s not necessarily because space and time are made up of discrete pixels. Rather, it’s because as you get closer to the Planck length, space and time stop being the most convenient way to describe things. For a relatively simple example of how this can work, see my post here.

From there, he reflects on holography: the discovery that certain theories in physics can be described equally well by what is happening on their boundary as by their interior, the way that a 2D page can hold all the information for an apparently 3D hologram. He talks about the Bekenstein bound, the conjecture that there is a maximum amount of information needed to describe a region of space, proportional not to the volume of the region but to its area. For Hoffman, this feels suspiciously like human vision: if we see just a 2D image of the world, could that image contain all the information needed to construct that world? Could the world really be just what we see?

In a word, no.

On the physics side, the Bekenstein bound is a conjecture, and one that doesn’t always hold. A more precise version that seems to hold more broadly, called the Bousso bound, works by demanding the surface have certain very specific geometric properties in space-time, properties not generally shared by the retinas of our eyes.

But it even fails in Hoffman’s own context, once we remember that there are other types of perception than vision. When we hear, we don’t detect a 2D map, but a 1D set of frequencies, put in “stereo” by our ears. When we feel pain, we can feel it in any part of our body, essentially a 3D picture since it goes inwards as well. Nothing about human perception uniquely singles out a 2D surface.

There is actually something in physics much closer to what Hoffman is imagining, but it trades on a principle Hoffman aspires to get rid of: locality. We’ve known since Einstein that you can’t change the world around you faster than the speed of light. Quantum mechanics doesn’t change that, despite what you may have heard. More than that, simultaneity is relative: two distant events might be at the same time in your reference frame, but for someone else one of them might be first, or the other one might be, there is no one universal answer.

Because of that, if you want to think about things happening one by one, cause following effect, actions causing consequences, then you can’t think of causes or actions as spread out in space. You have to think about what happens at a single point: the location of an imagined observer.

Once you have this concept, you can ask whether describing the world in terms of this single observer works just as well as describing it in terms of a wide open space. And indeed, it actually can do well, at least under certain conditions. But one again, this really isn’t how Hoffman is doing things: he has multiple observers all real at the same time, communicating with each other in a definite order.

In general, a lot of researchers in quantum gravity think spacetime is doomed. They think things are better described in terms of objects with other properties and interactions, with space and time as just convenient approximations for a more complicated reality. They get this both from observing properties of the theories we already have, and from thought experiments showing where those theories cause problems.

Nima, the most catchy of these quotable theorists, is approaching the problem from the direction of scattering amplitudes: the calculations we do to find the probability of observations in particle physics. Each scattering amplitude describes a single observation: what someone far away from a particle collision can measure, independent of any story of what might have “actually happened” to the particles in between. Nima’s goal is to describe these amplitudes purely in terms of those observations, to get rid of the “story” that shows up in the middle as much as possible.

The other theorists have different goals, but have this in common: they treat observables as their guide. They look at the properties that a single observer’s observations can have, and try to take a fresh view, independent of any assumptions about what happens in between.

This key perspective, this key insight, is what Hoffman is missing throughout this book. He has read what many physicists have to say, but he does not understand why they are saying it. His book is titled The Case Against Reality, but he merely trades one reality for another. He stops short of the more radical, more justified case against reality: that “reality”, that thing philosophers argue about and that makes us think we can rule out theories based on pure thought, is itself the wrong approach: that instead of trying to characterize an idealized real world, we are best served by focusing on what we can do.

One thing I didn’t do here is a full critique of Hoffman’s specific proposal, treating it as a proposed theory of physics. That would involve quite a bit more work, on top of what has turned out to be a very long book review. I would need to read not just his popular description, but the actual papers where he makes his case and lays out the relevant subtleties. Since I haven’t done that, I’ll end with a few questions: things that his proposal will need to answer if it aspires to be a useful idea for physics.

- Are the networks of conscious agents he proposes Turing-complete? In other words, can they represent any calculation a computer can do? If so, they aren’t a useful idea for physics, because you could imagine a network of conscious agents to reproduce any theory you want. The idea wouldn’t narrow things down to get us closer to a useful truth. This was also one of the things that made me uncomfortable with the Wolfram Physics Project.

- What are the conditions that allow a network of simple conscious agents to make up a bigger conscious agent? Do those conditions depend meaningfully on the network’s agents being conscious, or do they just have to pass messages? If the latter, then Hoffman is tacitly admitting you can make a conscious agent out of non-conscious agents, even if he insists this is philosophically impossible.

- How do you square this network with relativity and quantum mechanics? Is there a set time, an order in which all the conscious agents communicate with each other? If so, how do you square that with the relativity of simultaneity? Are the agents themselves supposed to be able to be put in quantum states, or is quantum mechanics supposed to emerge from a theory of classical agents?

- How does evolution fit in here? A bit part of Hoffman’s argument was supported by the universality of the evolutionary algorithm. In order for evolution to matter for your simplest agents, they need to be able to be created or destroyed. But then they have more than two actions: not just 0 and 1, but 0, 1, and cease to exist. So you could have an even simpler agent that has just two bits.