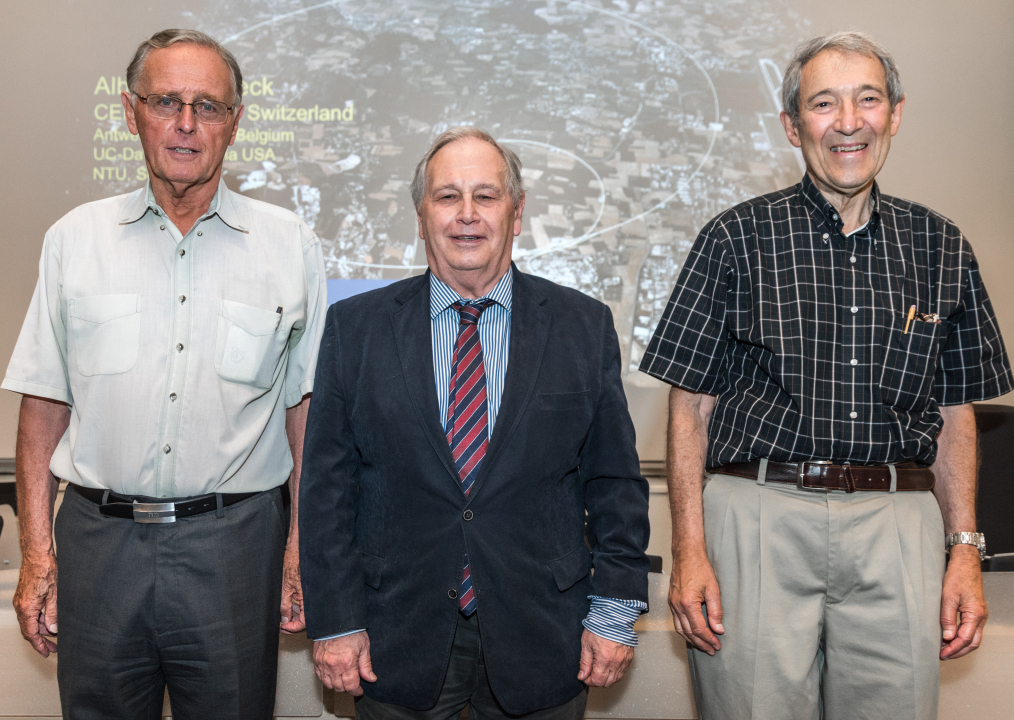

This week, $3 Million was awarded by the Breakthrough Prize to Sergio Ferrara, Daniel Z. Freedman and Peter van Nieuwenhuizen, the discoverers of the theory of supergravity, part of a special award separate from their yearly Fundamental Physics Prize. There’s a nice interview with Peter van Nieuwenhuizen on the Stony Brook University website, about his reaction to the award.

The Breakthrough Prize was designed to complement the Nobel Prize, rewarding deserving researchers who wouldn’t otherwise get the Nobel. The Nobel Prize is only awarded to theoretical physicists when they predict something that is later observed in an experiment. Many theorists are instead renowned for their mathematical inventions, concepts that other theorists build on and use but that do not by themselves make testable predictions. The Breakthrough Prize celebrates these theorists, and while it has also been awarded to others who the Nobel committee could not or did not recognize (various large experimental collaborations, Jocelyn Bell Burnell), this has always been the physics prize’s primary focus.

The Breakthrough Prize website describes supergravity as a theory that combines gravity with particle physics. That’s a bit misleading: while the theory does treat gravity in a “particle physics” way, unlike string theory it doesn’t solve the famous problems with combining quantum mechanics and gravity. (At least, as far as we know.)

It’s better to say that supergravity is a theory that links gravity to other parts of particle physics, via supersymmetry. Supersymmetry is a relationship between two types of particles: bosons, like photons, gravitons, or the Higgs, and fermions, like electrons or quarks. In supersymmetry, each type of boson has a fermion “partner”, and vice versa. In supergravity, gravity itself gets a partner, called the gravitino. Supersymmetry links the properties of particles and their partners together: both must have the same mass and the same charge. In a sense, it can unify different types of particles, explaining both under the same set of rules.

In the real world, we don’t see bosons and fermions with the same mass and charge. If gravitinos exist, then supersymmetry would have to be “broken”, giving them a high mass that makes them hard to find. Some hoped that the Large Hadron Collider could find these particles, but now it looks like it won’t, so there is no evidence for supergravity at the moment.

Instead, supergravity’s success has been as a tool to understand other theories of gravity. When the theory was proposed in the 1970’s, it was thought of as a rival to string theory. Instead, over the years it consistently managed to point out aspects of string theory that the string theorists themselves had missed, for example noticing that the theory needed not just strings but higher-dimensional objects called “branes”. Now, supergravity is understood as one part of a broader string theory picture.

In my corner of physics, we try to find shortcuts for complicated calculations. We benefit a lot from toy models: simpler, unrealistic theories that let us test our ideas before applying them to the real world. Supergravity is one of the best toy models we’ve got, a theory that makes gravity simple enough that we can start to make progress. Right now, colleagues of mine are developing new techniques for calculations at LIGO, the gravitational wave telescope. If they hadn’t worked with supergravity first, they would never have discovered these techniques.

The discovery of supergravity by Ferrara, Freedman, and van Nieuwenhuizen is exactly the kind of work the Breakthrough Prize was created to reward. Supergravity is a theory with deep mathematics, rich structure, and wide applicability. There is of course no guarantee that such a theory describes the real world. What is guaranteed, though, is that someone will find it useful.