As a kid, I was fascinated by cosmology. I wanted to know how the universe began, possibly disproving gods along the way, and I gobbled up anything that hinted at the answer.

At the time, I had to be content with vague slogans. As I learned more, I could match the slogans to the physics, to see what phrases like “the Big Bang” actually meant. A large part of why I went into string theory was to figure out what all those documentaries are actually about.

In the end, I didn’t end up working on cosmology due my ignorance of a few key facts while in college (mostly, who Vilenkin was). Thus, while I could match some of the old popularization stories to the science, there were a few I never really understood. In particular, there were two claims I never quite saw fleshed out: “The universe emerged from nothing via quantum tunneling” and “According to Hawking, the big bang was not a singularity, but a smooth change with no true beginning.”

As a result, I’m delighted that I’ve recently learned the physics behind these claims, in the context of a spirited take-down of both by Perimeter’s Director Neil Turok.

My boss

Neil held a surprise string group meeting this week to discuss the paper I linked above, “No smooth beginning for spacetime” with Job Feldbrugge and Jean-Luc Lehners, as well as earlier work with Steffen Gielen. In it, he talked about problems in the two proposals I mentioned: Hawking’s suggestion that the big bang was smooth with no true beginning (really, the Hartle-Hawking no boundary proposal) and the idea that the universe emerged from nothing via quantum tunneling (really, Vilenkin’s tunneling from nothing proposal).

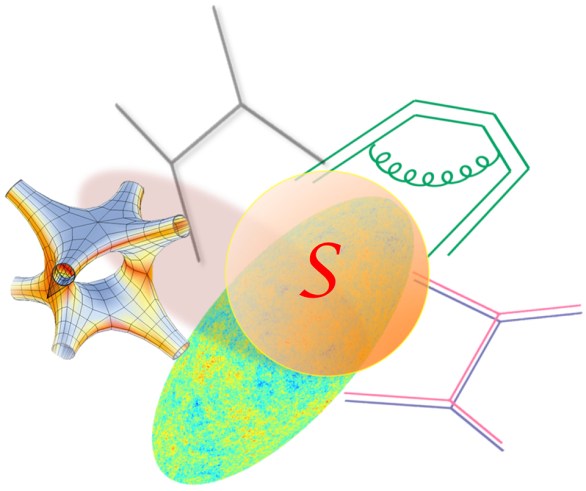

In popularization-speak, these two proposals sound completely different. In reality, though, they’re quite similar (and as Neil argues, they end up amounting to the same thing). I’ll steal a picture from his paper to illustrate:

The picture on the left depicts the universe under the Hartle-Hawking proposal, with time increasing upwards on the page. As the universe gets older, it looks like the expanding (de Sitter) universe we live in. At the beginning, though, there’s a cap, one on which time ends up being treated not in the usual way (Lorentzian space) but on the same footing as the other dimensions (Euclidean space). This lets space be smooth, rather than bunching up in a big bang singularity. After treating time in this way the result is reinterpreted (via a quantum field theory trick called Wick rotation) as part of normal space-time.

What’s the connection to Vilenkin’s tunneling picture? Well, when we talk about quantum tunneling, we also end up describing it with Euclidean space. Saying that the universe tunneled from nothing and saying it has a Euclidean “cap” then end up being closely related claims.

Before Neil’s work these two proposals weren’t thought of as the same because they were thought to give different results. What Neil is arguing is that this is due to a fundamental mistake on Hartle and Hawking’s part. Specifically, Neil is arguing that the Wick rotation trick that Hartle and Hawking used doesn’t work in this context, when you’re trying to calculate small quantum corrections for gravity. In normal quantum field theory, it’s often easier to go to Euclidean space and use Wick rotation, but for quantum gravity Neil is arguing that this technique stops being rigorous. Instead, you should stay in Lorentzian space, and use a more powerful mathematical technique called Picard-Lefschetz theory.

Using this technique, Neil found that Hartle and Hawking’s nicely behaved result was mistaken, and the real result of what Hartle and Hawking were proposing looks more like Vilenkin’s tunneling proposal.

Neil then tried to see what happens when there’s some small perturbation from a perfect de Sitter universe. In general in physics if you want to trust a result it ought to be stable: small changes should stay small. Otherwise, you’re not really starting from the right point, and you should instead be looking at wherever the changes end up taking you. What Neil found was that the Hartle-Hawking and Vilenkin proposals weren’t stable. If you start with a small wiggle in your no-boundary universe you get, not the purple middle drawing with small wiggles, but the red one with wiggles that rapidly grow unstable. The implication is that the Hartle-Hawking and Vilenkin proposals aren’t just secretly the same, they also both can’t be the stable state of the universe.

Neil argues that this problem is quite general, and happens under the following conditions:

- A universe that begins smoothly and semi-classically (where quantum corrections are small) with no sharp boundary,

- with a positive cosmological constant (the de Sitter universe mentioned earlier),

- under which the universe expands many times, allowing the small fluctuations to grow large.

If the universe avoids one of those conditions (maybe the cosmological constant changes in the future and the universe stops expanding, for example) then you might be able to avoid Neil’s argument. But if not, you can’t have a smooth semi-classical beginning and still have a stable universe.

Now, no debate in physics ends just like that. Hartle (and collaborators) don’t disagree with Neil’s insistence on Picard-Lefschetz theory, but they argue there’s still a way to make their proposal work. Neil mentioned at the group meeting that he thinks even the new version of Hartle’s proposal doesn’t solve the problem, he’s been working out the calculation with his collaborators to make sure.

Often, one hears about an idea from science popularization and then it never gets mentioned again. The public hears about a zoo of proposals without ever knowing which ones worked out. I think child-me would appreciate hearing what happened to Hawking’s proposal for a universe with no boundary, and to Vilenkin’s proposal for a universe emerging from nothing. Adult-me certainly does. I hope you do too.