I’ve heard people claim that in order to understand wormholes, you need to understand five-dimensional space.

Well that’s just silly.

A wormhole is often described as a hole in space-time. It can be imagined as a black hole where instead of getting crushed when you fall in to the center, you emerge somewhere else (or even some-when else: wormholes are possibly the only way to get time travel). They’re a staple of science fiction, even if they aren’t always portrayed accurately.

How does this work? Well like many things in physics, it’s helpful to imagine it with fewer dimensions first:

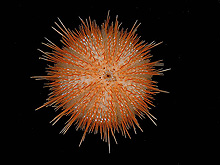

Suppose that you live on the surface of a donut. You can’t get up off the surface; you’re stuck to its gooey sugary coating. All you can do is slide around it.

Let’s say that one day you’re sitting on the pink side of the donut, near the center. Your friend lives on the non-frosted side, and you want to go see her. You could go all the way back to the outside edge of the donut, around the side, and down to the bottom, but you’re tired and the frosting is sticky. Luckily, you can use your futuristic pastry technology, the donut hole! Instead of going around the outside, you dive in through the inside hole, getting to your friend’s house much faster.

That’s really all a wormhole is. Instead of living on a two-dimensional donut surface, you live in a world with three space dimensions and one time dimension. A wormhole is still just like a donut hole: a shortcut, made possible by space being a non-obvious shape.

Now earlier I said that you don’t need to understand five-dimensional space to understand wormholes, and that’s true. Yes, real donuts exist in three dimensions…but if you live on the surface only, you only see two: inward versus outward, and around the center. It’s like a 2D video game with a limited map: the world looks flat, but if you go up past the top edge you find yourself on the bottom. Going from the top edge directly to the bottom is easier than going all the way down the screen: it’s just the same as a wormhole. You don’t need extra dimensions to have wormholes, just rules: when you go up far enough, you come back down. Go to the center of the wormhole, and come out the other side. And as one finds in physics, it’s the rules, not naïve intuitions, that determine how the world works. Just like a video game.