Last week, I mentioned some interesting new results in my corner of physics. I’ve now finally read the two papers and watched the recorded talk, so I can satisfy my frustrated commenters.

Quantum mechanics is a very cool topic and I am much less qualified than you would expect to talk about it. I use quantum field theory, which is based on quantum mechanics, so in some sense I use quantum mechanics every day. However, most of the “cool” implications of quantum mechanics don’t come up in my work. All the debates about whether measurement “collapses the wavefunction” are irrelevant when the particles you measure get absorbed in a particle detector, never to be seen again. And while there are deep questions about how a classical world emerges from quantum probabilities, they don’t matter so much when all you do is calculate those probabilities.

They’ve started to matter, though. That’s because quantum field theorists like me have recently started working on a very different kind of problem: trying to predict the output of gravitational wave telescopes like LIGO. It turns out you can do almost the same kind of calculation we’re used to: pretend two black holes or neutron stars are sub-atomic particles, and see what happens when they collide. This trick has grown into a sub-field in its own right, one I’ve dabbled in a bit myself. And it’s gotten my kind of physicists to pay more attention to the boundary between classical and quantum physics.

The thing is, the waves that LIGO sees really are classical. Any quantum gravity effects there are tiny, undetectably tiny. And while this doesn’t have the implications an expert might expect (we still need loop diagrams), it does mean that we need to take our calculations to a classical limit.

Figuring out how to do this has been surprisingly delicate, and full of unexpected insight. A recent example involves two papers, one by Andrea Cristofoli, Riccardo Gonzo, Nathan Moynihan, Donal O’Connell, Alasdair Ross, Matteo Sergola, and Chris White, and one by Ruth Britto, Riccardo Gonzo, and Guy Jehu. At first I thought these were two groups happening on the same idea, but then I noticed Riccardo Gonzo on both lists, and realized the papers were covering different aspects of a shared story. There is another group who happened upon the same story: Paolo Di Vecchia, Carlo Heissenberg, Rodolfo Russo and Gabriele Veneziano. They haven’t published yet, so I’m basing this on the Gonzo et al papers.

The key question each group asked was, what does it take for gravitational waves to be classical? One way to ask the question is to pick something you can observe, like the strength of the field, and calculate its uncertainty. Classical physics is deterministic: if you know the initial conditions exactly, you know the final conditions exactly. Quantum physics is not. What should happen is that if you calculate a quantum uncertainty and then take the classical limit, that uncertainty should vanish: the observation should become certain.

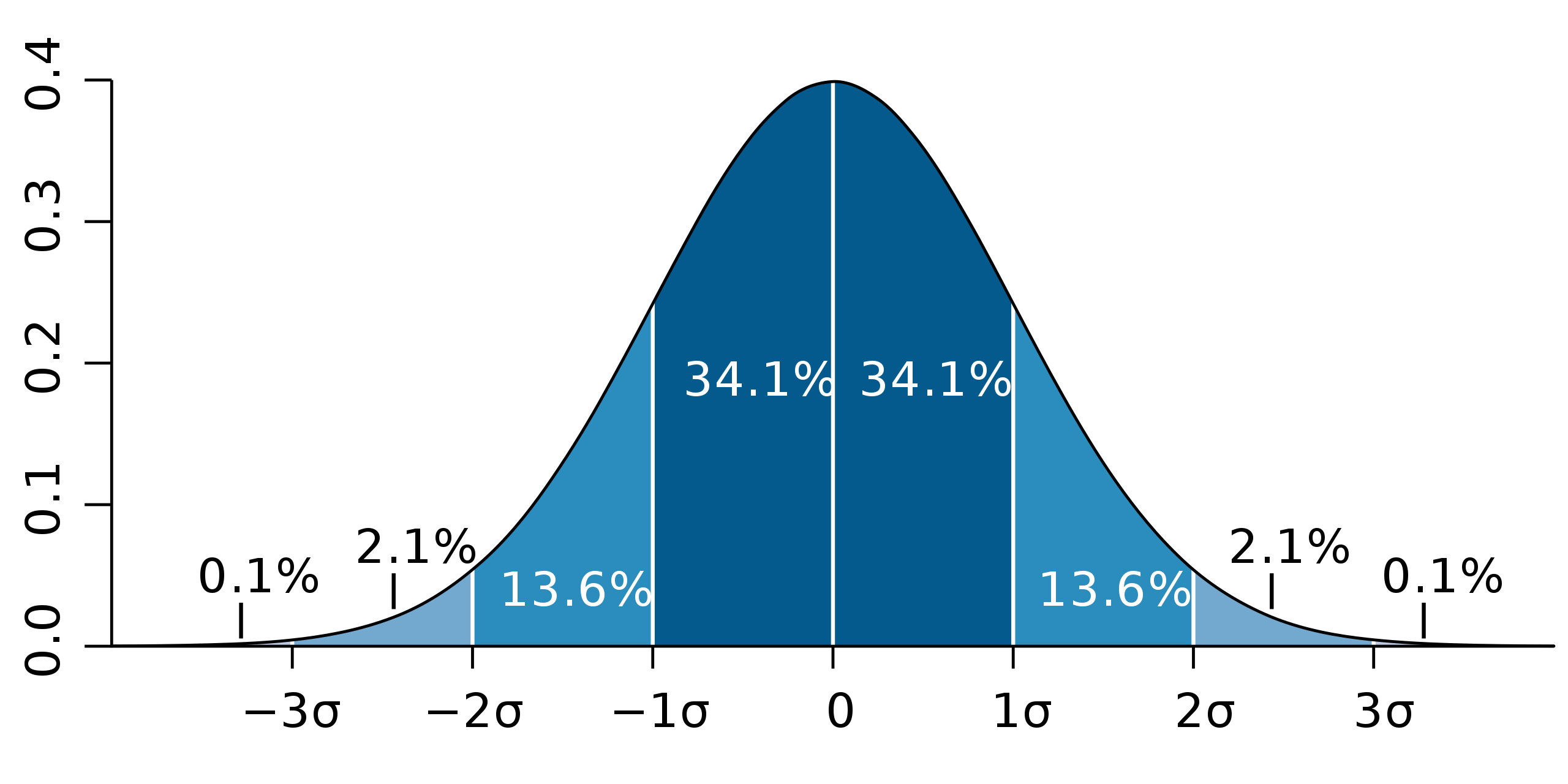

Another way to ask is to think about the wave as made up of gravitons, particles of gravity. Then you can ask how many gravitons are in the wave, and how they are distributed. It turns out that you expect them to be in a coherent state, like a laser, one with a very specific distribution called a Poisson distribution: a distribution in some sense right at the border between classical and quantum physics.

The results of both types of questions were as expected: the gravitational waves are indeed classical. To make this work, though, the quantum field theory calculation needs to have some surprising properties.

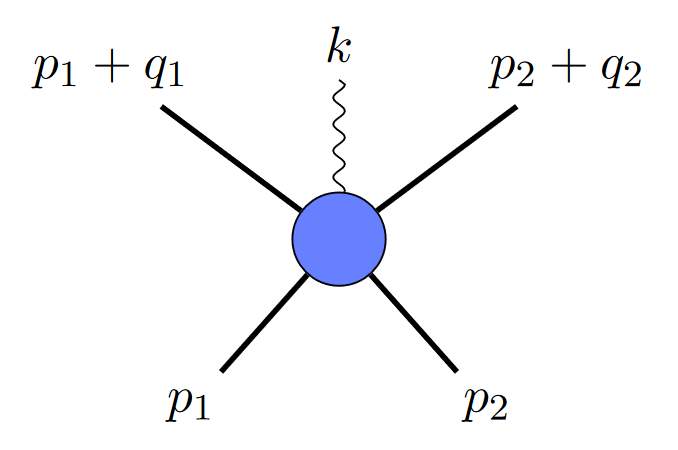

If two black holes collide and emit a gravitational wave, you could depict it like this:

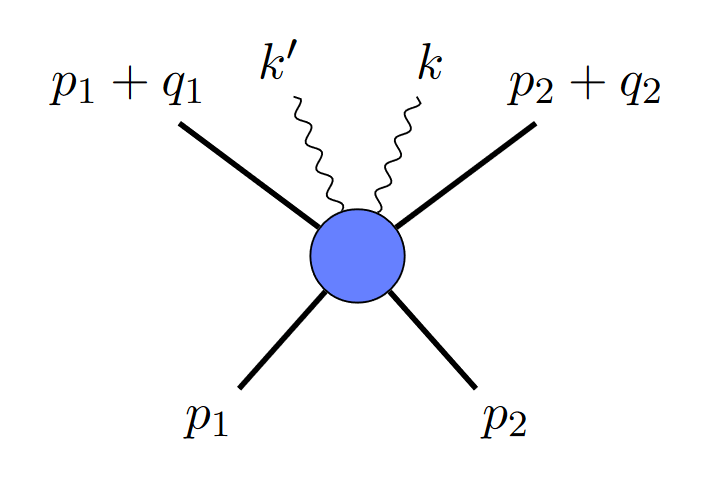

where the straight lines are black holes, and the squiggly line is a graviton. But since gravitational waves are made up of multiple gravitons, you might ask, why not depict it with two gravitons, like this?

It turns out that diagrams like that are a problem: they mean your two gravitons are correlated, which is not allowed in a Poisson distribution. In the uncertainty picture, they also would give you non-zero uncertainty. Somehow, in the classical limit, diagrams like that need to go away.

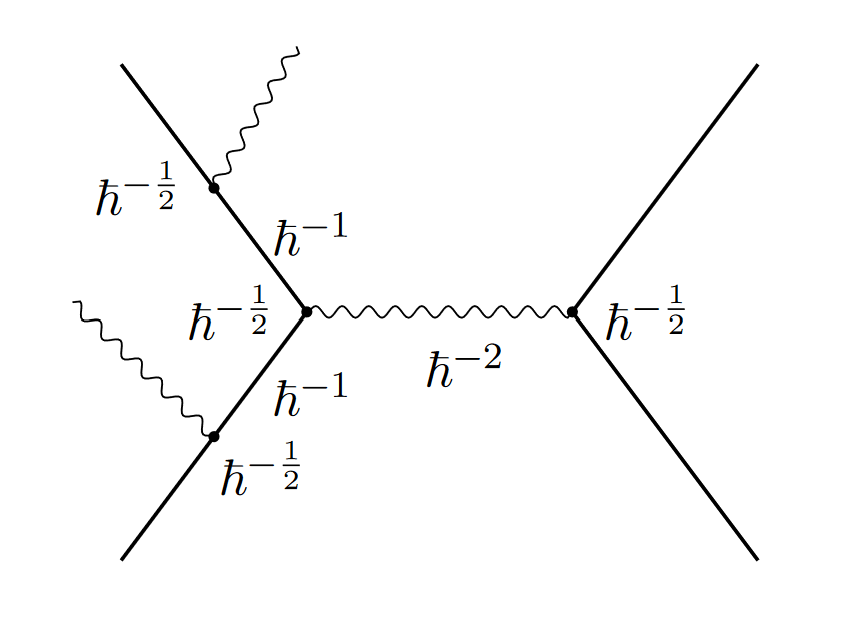

And at first, it didn’t look like they do. You can try to count how many powers of Planck’s constant show up in each diagram. The authors do that, and it certainly doesn’t look like it goes away:

Luckily, these quantum field theory calculations have a knack for surprising us. Calculate each individual diagram, and things look hopeless. But add them all together, and they miraculously cancel. In the classical limit, everything combines to give a classical result.

You can do this same trick for diagrams with more graviton particles, as many as you like, and each time it ought to keep working. You get an infinite set of relationships between different diagrams, relationships that have to hold to get sensible classical physics. From thinking about how the quantum and classical are related, you’ve learned something about calculations in quantum field theory.

That’s why these papers caught my eye. A chunk of my sub-field is needing to learn more and more about the relationship between quantum and classical physics, and it may have implications for the rest of us too. In the future, I might get a bit more qualified to talk about some of the very cool implications of quantum mechanics.