There’s a saying in physics, attributed to the famous genius John von Neumann: “With four parameters I can fit an elephant, and with five I can make him wiggle his trunk.”

Say you want to model something, like some surprising data from a particle collider. You start with some free parameters: numbers in your model that aren’t decided yet. You then decide those numbers, “fixing” them based on the data you want to model. Your goal is for your model not only to match the data, but to predict something you haven’t yet measured. Then you can go out and check, and see if your model works.

The more free parameters you have in your model, the easier this can go wrong. More free parameters make it easier to fit your data, but that’s because they make it easier to fit any data. Your model ends up not just matching the physics, but matching the mistakes as well: the small errors that crop up in any experiment. A model like that may look like it’s a great fit to the data, but its predictions will almost all be wrong. It wasn’t just fit, it was overfit.

We have statistical tools that tell us when to worry about overfitting, when we should be impressed by a model and when it has too many parameters. We don’t actually use these tools correctly, but they still give us a hint of what we actually want to know, namely, whether our model will make the right predictions. In a sense, these tools form the mathematical basis for Occam’s Razor, the idea that the best explanation is often the simplest one, and Occam’s Razor is a critical part of how we do science.

So, did you know machine learning was just modeling data?

All of the much-hyped recent advances in artificial intelligence, GPT and Stable Diffusion and all those folks, at heart they’re all doing this kind of thing. They start out with a model (with a lot more than five parameters, arranged in complicated layers…), then use data to fix the free parameters. Unlike most of the models physicists use, they can’t perfectly fix these numbers: there are too many of them, so they have to approximate. They then test their model on new data, and hope it still works.

Increasingly, it does, and impressively well, so well that the average person probably doesn’t realize this is what it’s doing. When you ask one of these AIs to make an image for you, what you’re doing is asking what image the model predicts would show up captioned with your text. It’s the same sort of thing as asking an economist what their model predicts the unemployment rate will be when inflation goes up. The machine learning model is just way, way more complicated.

As a physicist, the first time I heard about this, I had von Neumann’s quote in the back of my head. Yes, these machines are dealing with a lot more data, from a much more complicated reality. They literally are trying to fit elephants, even elephants wiggling their trunks. Still, the sheer number of parameters seemed fishy here. And for a little bit things seemed even more fishy, when I learned about double descent.

Suppose you start increasing the number of parameters in your model. Initially, your model gets better and better. Your predictions have less and less error, your error descends. Eventually, though, the error increases again: you have too many parameters so you’re over-fitting, and your model is capturing accidents in your data, not reality.

In machine learning, weirdly, this is often not the end of the story. Sometimes, your prediction error rises, only to fall once more, in a double descent.

For a while, I found this deeply disturbing. The idea that you can fit your data, start overfitting, and then keep overfitting, and somehow end up safe in the end, was terrifying. The way some of the popular accounts described it, like you were just overfitting more and more and that was fine, was baffling, especially when they seemed to predict that you could keep adding parameters, keep fitting tinier and tinier fleas on the elephant’s trunk, and your predictions would never start going wrong. It would be the death of Occam’s Razor as we know it, more complicated explanations beating simpler ones off to infinity.

Luckily, that’s not what happens. And after talking to a bunch of people, I think I finally understand this enough to say something about it here.

The right way to think about double descent is as overfitting prematurely. You do still expect your error to eventually go up: your model won’t be perfect forever, at some point you will really overfit. It might take a long time, though: machine learning people are trying to model very complicated things, like human behavior, with giant piles of data, so very complicated models may often be entirely appropriate. In the meantime, due to a bad choice of model, you can accidentally overfit early. You will eventually overcome this, pushing past with more parameters into a model that works again, but for a little while you might convince yourself, wrongly, that you have nothing more to learn.

(You can even mitigate this by tweaking your setup, potentially avoiding the problem altogether.)

So Occam’s Razor still holds, but with a twist. The best model is simple enough, but no simpler. And if you’re not careful enough, you can convince yourself that a too-simple model is as complicated as you can get.

I was reminded of all this recently by some articles by Sabine Hossenfelder.

Hossenfelder is a critic of mainstream fundamental physics. The articles were her restating a point she’s made many times before, including in (at least) one of her books. She thinks the people who propose new particles and try to search for them are wasting time, and the experiments motivated by those particles are wasting money. She’s motivated by something like Occam’s Razor, the need to stick to the simplest possible model that fits the evidence. In her view, the simplest models are those in which we don’t detect any more new particles any time soon, so those are the models she thinks we should stick with.

I tend to disagree with Hossenfelder. Here, I was oddly conflicted. In some of her examples, it seemed like she had a legitimate point. Others seemed like she missed the mark entirely.

Talk to most astrophysicists, and they’ll tell you dark matter is settled science. Indeed, there is a huge amount of evidence that something exists out there in the universe that we can’t see. It distorts the way galaxies rotate, lenses light with its gravity, and wiggled the early universe in pretty much the way you’d expect matter to.

What isn’t settled is whether that “something” interacts with anything else. It has to interact with gravity, of course, but everything else is in some sense “optional”. Astroparticle physicists use satellites to search for clues that dark matter has some other interactions: perhaps it is unstable, sometimes releasing tiny signals of light. If it did, it might solve other problems as well.

Hossenfelder thinks this is bunk (in part because she thinks those other problems are bunk). I kind of do too, though perhaps for a more general reason: I don’t think nature owes us an easy explanation. Dark matter isn’t obligated to solve any of our other problems, it just has to be dark matter. That seems in some sense like the simplest explanation, the one demanded by Occam’s Razor.

At the same time, I disagree with her substantially more on collider physics. At the Large Hadron Collider so far, all of the data is reasonably compatible with the Standard Model, our roughly half-century old theory of particle physics. Collider physicists search that data for subtle deviations, one of which might point to a general discrepancy, a hint of something beyond the Standard Model.

While my intuitions say that the simplest dark matter is completely dark, they don’t say that the simplest particle physics is the Standard Model. Back when the Standard Model was proposed, people might have said it was exceptionally simple because it had a property called “renormalizability”, but these days we view that as less important. Physicists like Ken Wilson and Steven Weinberg taught us to view theories as a kind of series of corrections, like a Taylor series in calculus. Each correction encodes new, rarer ways that particles can interact. A renormalizable theory is just the first term in this series. The higher terms might be zero, but they might not. We even know that some terms cannot be zero, because gravity is not renormalizable.

The two cases on the surface don’t seem that different. Dark matter might have zero interactions besides gravity, but it might have other interactions. The Standard Model might have zero corrections, but it might have nonzero corrections. But for some reason, my intuition treats the two differently: I would find it completely reasonable for dark matter to have no extra interactions, but very strange for the Standard Model to have no corrections.

I think part of where my intuition comes from here is my experience with other theories.

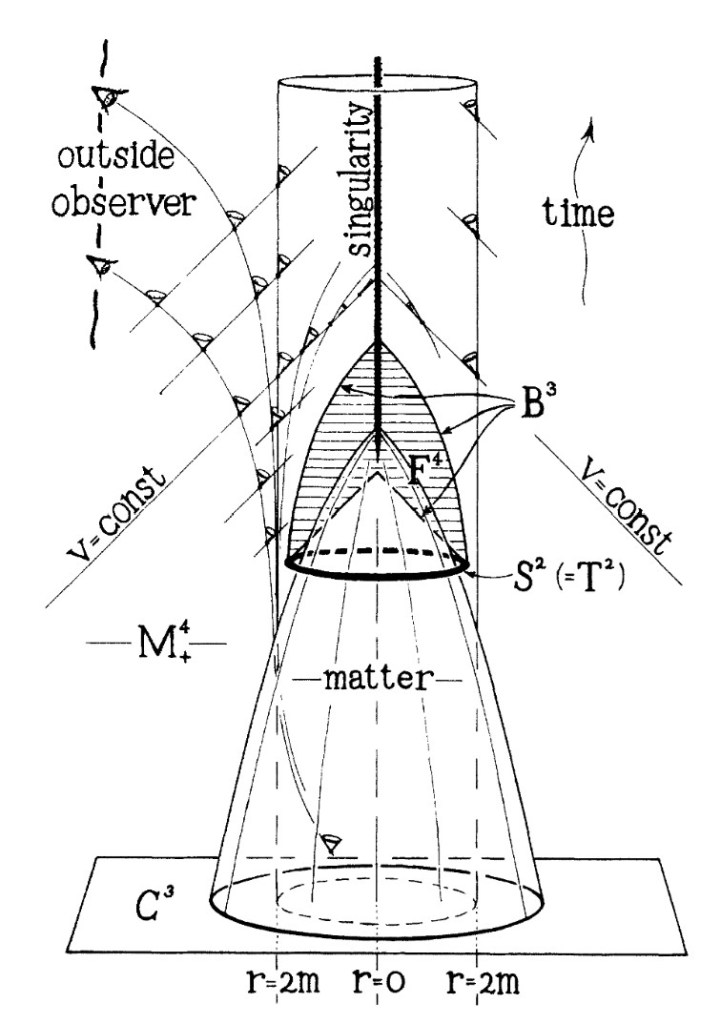

One example is a toy model called sine-Gordon theory. In sine-Gordon theory, this Taylor series of corrections is a very familiar Taylor series: the sine function! If you go correction by correction, you’ll see new interactions and more new interactions. But if you actually add them all up, something surprising happens. Sine-Gordon turns out to be a special theory, one with “no particle production”: unlike in normal particle physics, in sine-Gordon particles can neither be created nor destroyed. You would never know this if you did not add up all of the corrections.

String theory itself is another example. In string theory, elementary particles are replaced by strings, but you can think of that stringy behavior as a series of corrections on top of ordinary particles. Once again, you can try adding these things up correction by correction, but once again the “magic” doesn’t happen until the end. Only in the full series does string theory “do its thing”, and fix some of the big problems of quantum gravity.

If the real world really is a theory like this, then I think we have to worry about something like double descent.

Remember, double descent happens when our models can prematurely get worse before getting better. This can happen if the real thing we’re trying to model is very different from the model we’re using, like the example in this explainer that tries to use straight lines to match a curve. If we think a model is simpler because it puts fewer corrections on top of the Standard Model, then we may end up rejecting a reality with infinite corrections, a Taylor series that happens to add up to something quite nice. Occam’s Razor stops helping us if we can’t tell which models are really the simple ones.

The problem here is that every notion of “simple” we can appeal to here is aesthetic, a choice based on what makes the math look nicer. Other sciences don’t have this problem. When a biologist or a chemist wants to look for the simplest model, they look for a model with fewer organisms, fewer reactions…in the end, fewer atoms and molecules, fewer of the building-blocks given to those fields by physics. Fundamental physics can’t do this: we build our theories up from mathematics, and mathematics only demands that we be consistent. We can call theories simpler because we can write them in a simple way (but we could write them in a different way too). Or we can call them simpler because they look more like toy models we’ve worked with before (but those toy models are just a tiny sample of all the theories that are possible). We don’t have a standard of simplicity that is actually reliable.

There is one other way out of this pickle. A theory that is easier to write down is under no obligation to be true. But it is more likely to be useful. Even if the real world is ultimately described by some giant pile of mathematical parameters, if a simple theory is good enough for the engineers then it’s a better theory to aim for: a useful theory that makes peoples’ lives better.

I kind of get the feeling Hossenfelder would make this objection. I’ve seen her argue on twitter that scientists should always be able to say what their research is good for, and her Guardian article has this suggestive sentence: “However, we do not know that dark matter is indeed made of particles; and even if it is, to explain astrophysical observations one does not need to know details of the particles’ behaviour.”

Ok yes, to explain astrophysical observations one doesn’t need to know the details of dark matter particles’ behavior. But taking a step back, one doesn’t actually need to explain astrophysical observations at all.

Astrophysics and particle physics are not engineering problems. Nobody out there is trying to steer a spacecraft all the way across a galaxy, navigating the distribution of dark matter, or creating new universes and trying to make sure they go just right. Even if we might do these things some day, it will be so far in the future that our attempts to understand them won’t just be quaint: they will likely be actively damaging, confusing old research in dead languages that the field will be better off ignoring to start from scratch.

Because of that, usefulness is also not a meaningful guide. It cannot tell you which theories are more simple, which to favor with Occam’s Razor.

Hossenfelder’s highest-profile recent work falls afoul of one or the other of her principles. Her work on the foundations of quantum mechanics could genuinely be useful, but there’s no reason aside from claims of philosophical beauty to expect it to be true. Her work on modeling dark matter is at least directly motivated by data, but is guaranteed to not be useful.

I’m not pointing this out to call Hossenfelder a hypocrite, as some sort of ad hominem or tu quoque. I’m pointing this out because I don’t think it’s possible to do fundamental physics today without falling afoul of these principles. If you want to hold out hope that your work is useful, you don’t have a great reason besides a love of pretty math: otherwise, anything useful would have been discovered long ago. If you just try to model existing data as best you can, then you’re making a model for events far away or locked in high-energy particle colliders, a model no-one else besides other physicists will ever use.

I don’t know the way through this. I think if you need to take Occam’s Razor seriously, to build on the same foundations that work in every other scientific field…then you should stop doing fundamental physics. You won’t be able to make it work. If you still need to do it, if you can’t give up the sub-field, then you should justify it on building capabilities, on the kind of “practice” Hossenfelder also dismisses in her Guardian piece.

We don’t have a solid foundation, a reliable notion of what is simple and what isn’t. We have guesses and personal opinions. And until some experiment uncovers some blinding flash of new useful meaningful magic…I don’t think we can do any better than that.