A few weeks back, Caltech’s Institute of Quantum Information and Matter released a short film titled Quantum is Calling. It’s the second in what looks like will become a series of pieces featuring Hollywood actors popularizing ideas in physics. The first used the game of Quantum Chess to talk about superposition and entanglement. This one, featuring Zoe Saldana, is about a conjecture by Juan Maldacena and Leonard Susskind called ER=EPR. The conjecture speculates that pairs of entangled particles (as investigated by Einstein, Podolsky, and Rosen) are in some sense secretly connected by wormholes (or Einstein-Rosen bridges).

The film is fun, but I’m not sure ER=EPR is established well enough to deserve this kind of treatment.

At this point, some of you are nodding your heads for the wrong reason. You’re thinking I’m saying this because ER=EPR is a conjecture.

I’m not saying that.

The fact of the matter is, conjectures play a very important role in theoretical physics, and “conjecture” covers a wide range. Some conjectures are supported by incredibly strong evidence, just short of mathematical proof. Others are wild speculations, “wouldn’t it be convenient if…” ER=EPR is, well…somewhere in the middle.

Most popularizers don’t spend much effort distinguishing things in this middle ground. I’d like to talk a bit about the different sorts of evidence conjectures can have, using ER=EPR as an example.

The first level of evidence is motivation.

At its weakest, motivation is the “wouldn’t it be convenient if…” line of reasoning. Some conjectures never get past this point. Hawking’s chronology protection conjecture, for instance, points out that physics (and to some extent logic) has a hard time dealing with time travel, and wouldn’t it be convenient if time travel was impossible?

For ER=EPR, this kind of motivation comes from the black hole firewall paradox. Without going into it in detail, arguments suggested that the event horizons of older black holes would resemble walls of fire, incinerating anything that fell in, in contrast with Einstein’s picture in which passing the horizon has no obvious effect at the time. ER=EPR provides one way to avoid this argument, making event horizons subtle and smooth once more.

Motivation isn’t just “wouldn’t it be convenient if…” though. It can also include stronger arguments: suggestive comparisons that, while they could be coincidental, when put together draw a stronger picture.

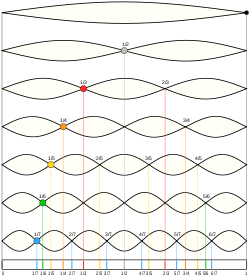

In ER=EPR, this comes from certain similarities between the type of wormhole Maldacena and Susskind were considering, and pairs of entangled particles. Both connect two different places, but both do so in an unusually limited way. The wormholes of ER=EPR are non-traversable: you cannot travel through them. Entangled particles can’t be traveled through (as you would expect), but more generally can’t be communicated through: there are theorems to prove it. This is the kind of suggestive similarity that can begin to motivate a conjecture.

(Amusingly, the plot of the film breaks this in both directions. Keanu Reeves can neither steal your cat through a wormhole, nor send you coded messages with entangled particles.)

Motivation is a good reason to investigate something, but a bad reason to believe it. Luckily, conjectures can have stronger forms of evidence. Many of the strongest conjectures are correspondences, supported by a wealth of non-trivial examples.

In science, the gold standard has always been experimental evidence. There’s a reason for that: when you do an experiment, you’re taking a risk. Doing an experiment gives reality a chance to prove you wrong. In a good experiment (a non-trivial one) the result isn’t obvious from the beginning, so that success or failure tells you something new about the universe.

In theoretical physics, there are things we can’t test with experiments, either because they’re far beyond our capabilities or because the claims are mathematical. Despite this, the overall philosophy of experiments is still relevant, especially when we’re studying a correspondence.

“Correspondence” is a word we use to refer to situations where two different theories are unexpectedly computing the same thing. Often, these are very different theories, living in different dimensions with different sorts of particles. With the right “dictionary”, though, you can translate between them, doing a calculation in one theory that matches a calculation in the other one.

Even when we can’t do non-trivial experiments, then, we can still have non-trivial examples. When the result of a calculation isn’t obvious from the beginning, showing that it matches on both sides of a correspondence takes the same sort of risk as doing an experiment, and gives the same sort of evidence.

Some of the best-supported conjectures in theoretical physics have this form. AdS/CFT is technically a conjecture: a correspondence between string theory in a hyperbola-shaped space and my favorite theory, N=4 super Yang-Mills. Despite being a conjecture, the wealth of nontrivial examples is so strong that it would be extremely surprising if it turned out to be false.

ER=EPR is also a correspondence, between entangled particles on the one hand and wormholes on the other. Does it have nontrivial examples?

Some, but not enough. Originally, it was based on one core example, an entangled state that could be cleanly matched to the simplest wormhole. Now, new examples have been added, covering wormholes with electric fields and higher spins. The full “dictionary” is still unclear, with some pairs of entangled particles being harder to describe in terms of wormholes. So while this kind of evidence is being built, it isn’t as solid as our best conjectures yet.

I’m fine with people popularizing this kind of conjecture. It deserves blog posts and press articles, and it’s a fine idea to have fun with. I wouldn’t be uncomfortable with the Bohemian Gravity guy doing a piece on it, for example. But for the second installment of a star-studded series like the one Caltech is doing…it’s not really there yet, and putting it there gives people the wrong idea.

I hope I’ve given you a better idea of the different types of conjectures, from the most fuzzy to those just shy of certain. I’d like to do this kind of piece more often, though in future I’ll probably stick with topics in my sub-field (where I actually know what I’m talking about 😉 ). If there’s a particular conjecture you’re curious about, ask in the comments!