Perimeter had its last Public Lecture of the season this week, with Mario Livio giving some highlights from his book Brilliant Blunders. The lecture should be accessible online, either here or on Perimeter’s YouTube page.

These lectures tend to attract a crowd of curious science-fans. To give them something to do while they’re waiting, a few local researchers walk around with T-shirts that say “Ask me, I’m a scientist!” Sometimes we get questions about the upcoming lecture, but more often people just ask us what they’re curious about.

Long-time readers will know that I find this one of the most fun parts of the job. In particular, there’s a unique challenge in figuring out just why someone asked a question. Often, there’s a hidden misunderstanding they haven’t recognized.

The fun thing about these misunderstandings is that they usually make sense, provided you’re working from the person in question’s sources. They heard a bit of this and a bit of that, and they come to the most reasonable conclusion they can given what’s available. For those of us who have heard a more complete story, this often leads to misunderstandings we would never have thought of, but that in retrospect are completely understandable.

One of the simpler ones I ran into was someone who was confused by people claiming that we were running out of water. How could there be a water shortage, he asked, if the Earth is basically a closed system? Where could the water go?

The answer is that when people are talking about a water shortage, they’re not talking about water itself running out. Rather, they’re talking about a lack of safe drinking water. Maybe the water is polluted, or stuck in the ocean without expensive desalinization. This seems like the sort of thing that would be extremely obvious, but if you just hear people complaining that water is running out without the right context then you might just not end up hearing that part of the story.

A more involved question had to do with time dilation in general relativity. The guy had heard that atomic clocks run faster if you’re higher up, and that this was because time itself runs faster in lower gravity.

Given that, he asked, what happens if someone travels to an area of low gravity and then comes back? If more time has passed for them, then they’d be in the future, so wouldn’t they be at the “wrong time” compared to other people? Would they even be able to interact with them?

This guy’s misunderstanding came from hearing what happens, but not why. While he got that time passes faster in lower gravity, he was still thinking of time as universal: there is some past, and some future, and if time passes faster for one person and slower for another that just means that one person is “skipping ahead” into the other person’s future.

What he was missing was the explanation that time dilation comes from space and time bending. Rather than “skipping ahead”, a person for whom time passes faster just experiences more time getting to the same place, because they’re traveling on a curved path through space-time.

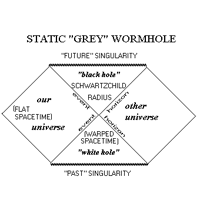

As usual, this is easier to visualize in space than in time. I ended up drawing a picture like this:

Imagine person A and person B live on a circle. If person B stays the same distance from the center while person A goes out further, they can both travel the same angle around the circle and end up in the same place, but A will have traveled further, even ignoring the trips up and down.

What’s completely intuitive in space ends up quite a bit harder to visualize in time. But if you at least know what you’re trying to think about, that there’s bending involved, then it’s easier to avoid this guy’s kind of misunderstanding. Run into the wrong account, though, and even if it’s perfectly correct (this guy had heard some of Hawking’s popularization work on the subject), if it’s not emphasizing the right aspects you can come away with the wrong impression.

Misunderstandings are interesting because they reveal how people learn. They’re windows into different thought processes, into what happens when you only have partial evidence. And because of that, they’re one of the most fascinating parts of science popularization.