I’ve got a new paper out this week with Andrew McLeod. I’m thinking of it as another entry in this year’s “cabinet of curiosities”, interesting Feynman diagrams with unusual properties. Although this one might be hard to fit into a cabinet.

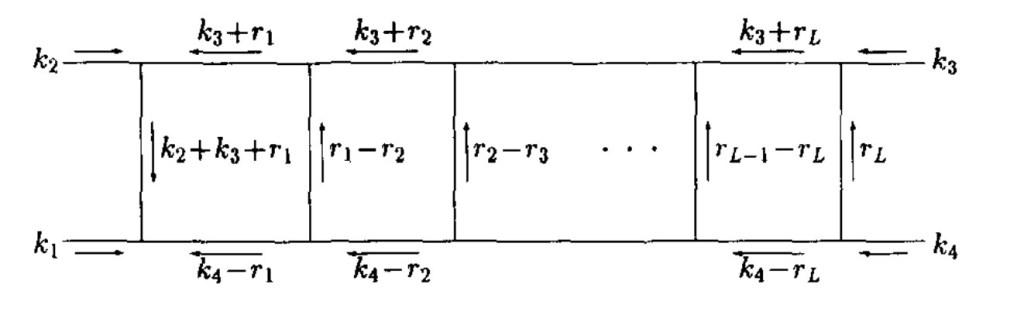

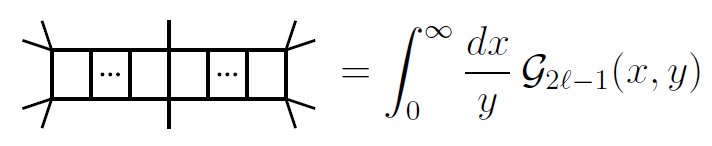

Over the past few years, I’ve been finding Feynman diagrams with interesting connections to Calabi-Yau manifolds, the spaces originally studied by string theorists to roll up their extra dimensions. With Andrew and other collaborators, I found an interesting family of these diagrams called traintracks, which involve higher-and-higher dimensional manifolds as they get longer and longer.

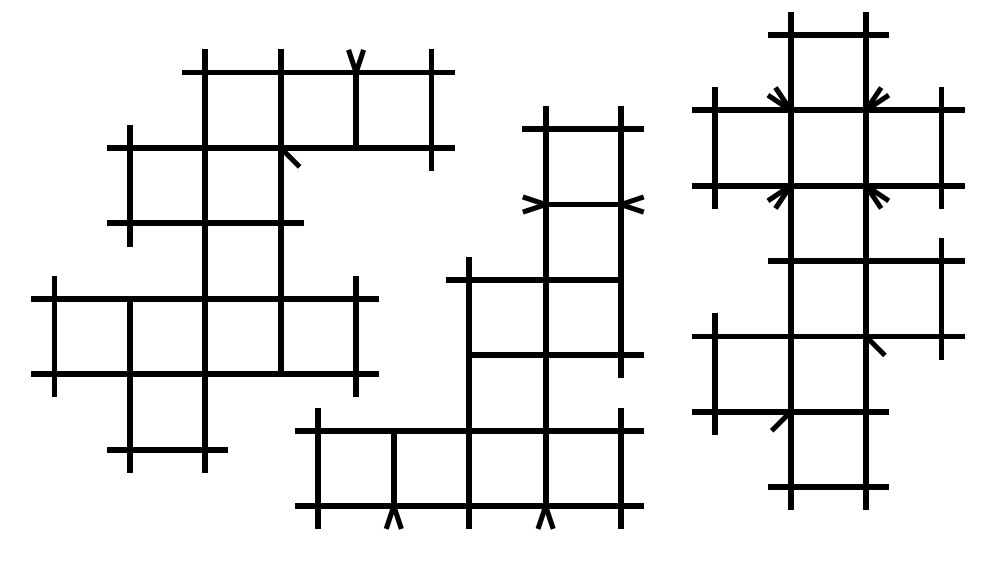

This time, we started hooking up our traintracks together.

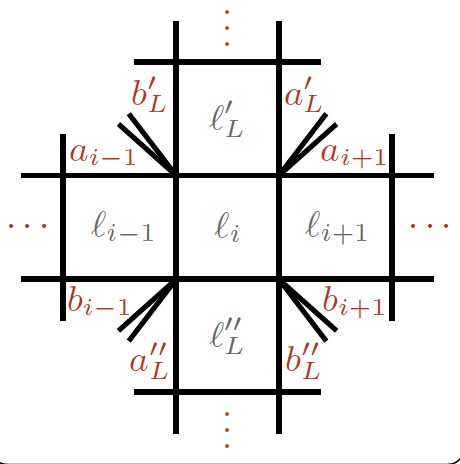

We call diagrams like these traintrack network diagrams, or traintrack networks for short. The original traintracks just went “one way”: one family, going higher in Calabi-Yau dimension the longer they got. These networks branch out, one traintrack leading to another and another.

In principle, these are much more complicated diagrams. But we find we can work with them in almost the same way. We can find the same “starting point” we had for the original traintracks, the set of integrals used to find the Calabi-Yau manifold. We’ve even got more reliable tricks, a method recently honed by some friends of ours that consistently find a Calabi-Yau manifold inside the original traintracks.

Surprisingly, though, this isn’t enough.

It works for one type of traintrack network, a so-called “cross diagram” like this:

But for other diagrams, if the network branches any more, the trick stops working. We still get an answer, but that answer is some more general space, not just a Calabi-Yau manifold.

That doesn’t mean that these general traintrack networks don’t involve Calabi-Yaus at all, mind you: it just means this method doesn’t tell us one way or the other. It’s also possible that simpler versions of these diagrams, involving fewer particles, will once again involve Calabi-Yaus. This is the case for some similar diagrams in two dimensions. But it’s starting to raise a question: how special are the Calabi-Yau related diagrams? How general do we expect them to be?

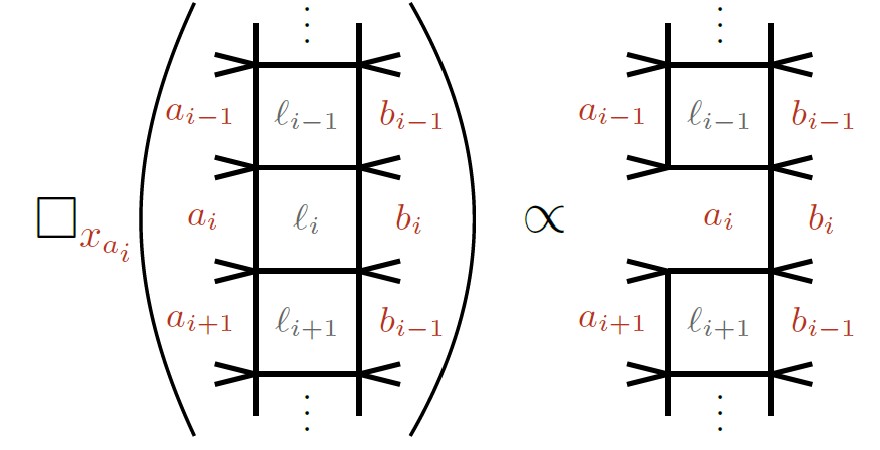

Another fun thing we noticed has to do with differential equations. There are equations that relate one diagram to another simpler one. We’ve used them in the past to build up “ladders” of diagrams, relating each picture to one with one of its boxes “deleted”. We noticed, playing with these traintrack networks, that these equations do a bit more than we thought. “Deleting” a box can make a traintrack short, but it can also chop a traintrack in half, leaving two “dangling” pieces, one on either side.

This reminded me of an important point, one we occasionally lose track of. The best-studied diagrams related to Calabi-Yaus are called “sunrise” diagrams. If you squish together a loop in one of those diagrams, the whole diagram squishes together, becoming much simpler. Because of that, we’re used to thinking of these as diagrams with a single “geometry”, one that shows up when you don’t “squish” anything.

Traintracks, and traintrack networks, are different. “Squishing” the diagram, or “deleting” a box, gives you a simpler diagram, but not much simpler. In particular, the new diagram will still contain traintracks, and traintrack networks. That means that we really should think of each traintrack network not just as one “top geometry”, but of a collection of geometries, different Calabi-Yaus that break into different combinations of Calabi-Yaus in different ways. It’s something we probably should have anticipated, but the form these networks take is a good reminder, one that points out that we still have a lot to do if we want to understand these diagrams.