Congratulations to Takaaki Kajita and Arthur McDonald, winners of this year’s Nobel Prize in Physics, as well as to the Super-Kamiokande and SNOLAB teams that made their work possible.

Unlike last year’s Nobel, this is one I’ve been anticipating for quite some time. Kajita and McDonald discovered that neutrinos have mass, and that discovery remains our best hint that there is something out there beyond the Standard Model.

But I’m getting a bit ahead of myself.

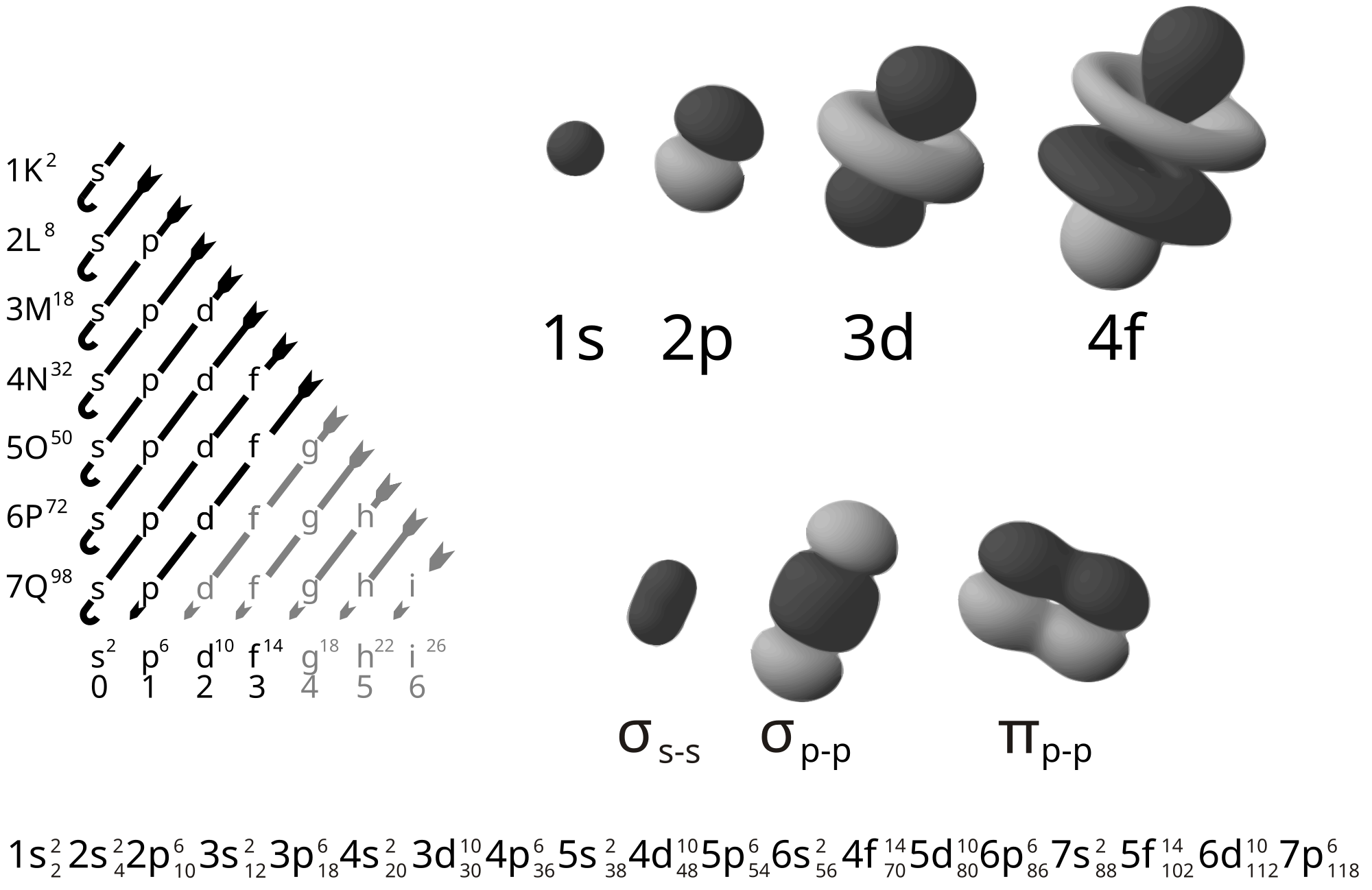

Neutrinos are the lightest of the fundamental particles, and for a long time they were thought to be completely massless. Their name means “little neutral one”, and it’s probably the last time physicists used “-ino” to mean “little”. Neutrinos are “neutral” because they have no electrical charge. They also don’t interact with the strong nuclear force. Only the weak nuclear force has any effect on them. (Well, gravity does too, but very weakly.)

This makes it very difficult to detect neutrinos: you have to catch them interacting via the weak force, which is, well, weak. Originally, that meant they had to be inferred by their absence: missing energy in nuclear reactions carried away by “something”. Now, they can be detected, but it requires massive tanks of fluid, carefully watched for the telltale light of the rare interactions between neutrinos and ordinary matter. You wouldn’t notice if billions of neutrinos passed through you every second, like an unstoppable army of ghosts. And in fact, that’s exactly what happens!

In the 60’s, scientists began to use these giant tanks of fluid to detect neutrinos coming from the sun. An enormous amount of effort goes in to understanding the sun, and these days our models of it are pretty accurate, so it came as quite a shock when researchers observed only half the neutrinos they expected. It wasn’t until the work of Super-Kamiokande in 1998, and SNOLAB in 2001, that we knew the reason why.

As it turns out, neutrinos oscillate. Neutrinos are produced in what are called flavor states, which match up with the different types of leptons. There are electron-neutrinos, muon-neutrinos, and tau-neutrinos.

Radioactive processes usually produce electron-neutrinos, so those are the type that the sun produces. But on their way from the sun to the earth, these neutrinos “oscillate”: they switch between electron neutrinos and the other types! The older detectors, focused only on electron-neutrinos, couldn’t see this. SNOLAB’s big advantage was that it could detect the other types of neutrinos as well, and tell the difference between them, which allowed it to see that the “missing” neutrinos were really just turning into other flavors! Meanwhile, Super-Kamiokande measured neutrinos coming not from the sun, but from cosmic rays reacting with the upper atmosphere. Some of these neutrinos came from the sky above the detector, while others traveled all the way through the earth below it, from the atmosphere on the other side. By observing “missing” neutrinos coming from below but not from above, Super-Kamiokande confirmed that it wasn’t the sun’s fault that we were missing solar neutrinos, neutrinos just oscillate!

What does this oscillation have to do with neutrinos having mass, though?

Here things get a bit trickier. I’ve laid some of the groundwork in older posts. I’ve told you to think about mass as “energy we haven’t met yet”, as the energy something has when we leave it alone to itself. I’ve also mentioned that conservation laws come from symmetries of nature, that energy conservation is a result of symmetry in time.

This should make it a little more plausible when I say that when something has a specific mass, it doesn’t change. It can decay into other particles, or interact with other forces, but left alone, by itself, it won’t turn into something else. To be more specific, it doesn’t oscillate. A state with a fixed mass is symmetric in time.

The only way neutrinos can oscillate between flavor states, then, is if one flavor state is actually a combination (in quantum terms, a superposition) of different masses. The components with different masses move at different speeds, so at any point along their path you can be more or less likely to see certain masses of neutrinos. As the mix of masses changes, the flavor state changes, so neutrinos end up oscillating from electron-neutrino, to muon-neutrino, to tau-neutrino.

So because of neutrino oscillation, neutrinos have to have mass. But this presented a problem. Most fundamental particles get their mass from interacting with the Higgs field. But, as it turns out, neutrinos can’t interact with the Higgs field. This has to do with the fact that neutrinos are “chiral”, and only come in a “left-handed” orientation. Only if they had both types of “handedness” could they get their mass from the Higgs.

As-is, they have to get their mass another way, and that way has yet to be definitively shown. Whatever it ends up being, it will be beyond the current Standard Model. Maybe there actually are right-handed neutrinos, but they’re too massive, or interact too weakly, for them to have been discovered. Maybe neutrinos are Majorana particles, getting mass in a novel way that hasn’t been seen yet in the Standard Model.

Whatever we discover, neutrinos are currently our best evidence that something lies beyond the Standard Model. Naturalness may have philosophical problems, dark matter may be explained away by modified gravity…but if neutrinos have mass, there’s something we still have yet to discover. And that definitely seems worthy of a Nobel to me!