Last week, Sabine Hossenfelder wrote a post entitled “Why not string theory?” In it, she argued that string theory has a much more dominant position in physics than it ought to: that it’s crowding out alternative theories like Loop Quantum Gravity and hogging much more funding than it actually merits.

If you follow the string wars at all, you’ve heard these sorts of arguments before. There’s not really anything new here.

That said, there were a few sentences in Hossenfelder’s post that got my attention, and inspired me to write this post.

So far, string theory has scored in two areas. First, it has proved interesting for mathematicians. But I’m not one to easily get floored by pretty theorems – I care about math only to the extent that it’s useful to explain the world. Second, string theory has shown to be useful to push ahead with the lesser understood aspects of quantum field theories. This seems a fruitful avenue and is certainly something to continue. However, this has nothing to do with string theory as a theory of quantum gravity and a unification of the fundamental interactions.

(Bolding mine)

Here, Hossenfelder explicitly leaves out string theorists who work on “lesser understood aspects of quantum field theories” from her critique. They’re not the big, dominant program she’s worried about.

What Hossenfelder doesn’t seem to realize is that right now, it is precisely the “aspects of quantum field theories” crowd that is big and dominant. The communities of string theorists working on something else, and especially those making bold pronouncements about the nature of the real world, are much, much smaller.

Let’s define some terms:

Phenomenology (or pheno for short) is the part of theoretical physics that attempts to make predictions that can be tested in experiments. String pheno, then, covers attempts to use string theory to make predictions. In practice, though, it’s broader than that: while some people do attempt to predict the results of experiments, more work on figuring out how models constructed by other phenomenologists can make sense in string theory. This still attempts to test string theory in some sense: if a phenomenologist’s model turns out to be true but it can’t be replicated in string theory then string theory would be falsified. That said, it’s more indirect. In parallel to string phenomenology, there is also the related field of string cosmology, which has a similar relationship with cosmology.

If other string theorists aren’t trying to make predictions, what exactly are they doing? Well, a large number of them are studying quantum field theories. Quantum field theories are currently our most powerful theories of nature, but there are many aspects of them that we don’t yet understand. For a large proportion of string theorists, string theory is useful because it provides a new way to understand these theories in terms of different configurations of string theory, which often uncovers novel and unexpected properties. This is still physics, not mathematics: the goal, in the end, is to understand theories that govern the real world. But it doesn’t involve the same sort of direct statements about the world as string phenomenology or string cosmology: crucially, it doesn’t depend on whether string theory is true.

Last week, I said that before replying to Hossenfelder’s post I’d have to gather some numbers. I was hoping to find some statistics on how many people work on each of these fields, or on their funding. Unfortunately, nobody seems to collect statistics broken down by sub-field like this.

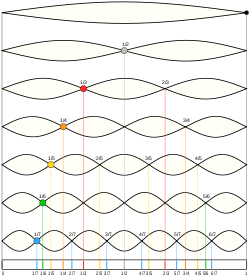

As a proxy, though, we can look at conferences. Strings is the premier conference in string theory. If something has high status in the string community, it will probably get a talk at Strings. So to investigate, I took a look at the talks given last year, at Strings 2015, and broke them down by sub-field.

Here I’ve left out the historical overview talks, since they don’t say much about current research.

“QFT” is for talks about lesser understood aspects of quantum field theories. Amplitudes, my own sub-field, should be part of this: I’ve separated it out to show what a typical sub-field of the QFT block might look like.

“Formal Strings” refers to research into the fundamentals of how to do calculations in string theory: in principle, both the QFT folks and the string pheno folks find it useful.

“Holography” is a sub-topic of string theory in which string theory in some space is equivalent to a quantum field theory on the boundary of that space. Some people study this because they want to learn about quantum field theory from string theory, others because they want to learn about quantum gravity from quantum field theory. Since the field can’t be cleanly divided into quantum gravity and quantum field theory research, I’ve given it its own category.

While all string theory research is in principle about quantum gravity, the “Quantum Gravity” section refers to people focused on the sorts of topics that interest non-string quantum gravity theorists, like black hole entropy.

Finally, we have String Cosmology and String Phenomenology, which I’ve already defined.

Don’t take the exact numbers here too seriously: not every talk fit cleanly into a category, so there were some judgement calls on my part. Nonetheless, this should give you a decent idea of the makeup of the string theory community.

The biggest wedge in the diagram by far, taking up a majority of the talks, is QFT. Throwing in Amplitudes (part of QFT) and Formal Strings (useful to both), and you’ve got two thirds of the conference. Even if you believe Hossenfelder’s tale of the failures of string theory, then, that only matters to a third of this diagram. And once you take into account that many of the Holography and Quantum Gravity people are interested in aspects of QFT as well, you’re looking at an even smaller group. Really, Hossenfelder’s criticism is aimed at two small slices on the chart: String Pheno, and String Cosmo.

Of course, string phenomenologists also have their own conference. It’s called String Pheno, and last year it had 130 participants. In contrast, LOOPS’ 2015, the conference for string theory’s most famous “rival”, had…190 participants. The fields are really pretty comparable.

Now, I have a lot more sympathy for the string phenomenologists and string cosmologists than I do for loop quantum gravity. If other string theorists felt the same way, then maybe that would cause the sort of sociological effect that Hossenfelder is worried about.

But in practice, I don’t think this happens. I’ve met string theorists who didn’t even know that people still did string phenomenology. The two communities are almost entirely disjoint: string phenomenologists and string cosmologists interact much more with other phenomenologists and cosmologists than they do with other string theorists.

You want to talk about sociology? Sociologically, people choose careers and fund research because they expect something to happen soon. People don’t want to be left high and dry by a dearth of experiments, don’t feel comfortable working on something that may only be vindicated long after they’re dead. Most people choose the safe option, the one that, even if it’s still aimed at a distant goal, is also producing interesting results now (aspects of quantum field theories, for example).

The people that don’t? Tend to form small, tight-knit, passionate communities. They carve out a few havens of like-minded people, and they think big thoughts while the world around them seems to only care about their careers.

If you’re a loop quantum gravity theorist, or a quantum gravity phenomenologist like Hossenfelder, and you see some of your struggles in that paragraph, please realize that string phenomenology is like that too.

I feel like Hossenfelder imagines a world in which string theory is struck from its high place, and alternative theories of quantum gravity are of comparable size and power. But from where I’m sitting, it doesn’t look like it would work out that way. Instead, you’d have alternatives grow to the same size as similarly risky parts of string theory, like string phenomenology. And surprise, surprise: they’re already that size.

In certain corners of the internet, people like to argue about “punching up” and “punching down”. Hossenfelder seems to think she’s “punching up”, giving the big dominant group a taste of its own medicine. But by leaving out string theorists who study QFTs, she’s really “punching down”, or at least sideways, and calling out a sub-group that doesn’t have much more power than her own.