If you follow astronomers on twitter, you may have heard some rumblings. For the last week or so, a few big collaborations have been hyping up an announcement of “something big”.

Those who knew who those collaborations were could guess the topic. Everyone else found out on Wednesday, when the alphabet soup of NANOGrav, EPTA, PPTA, CPTA, and InPTA announced detection of a gravitational wave background.

Who are these guys? And what have they found?

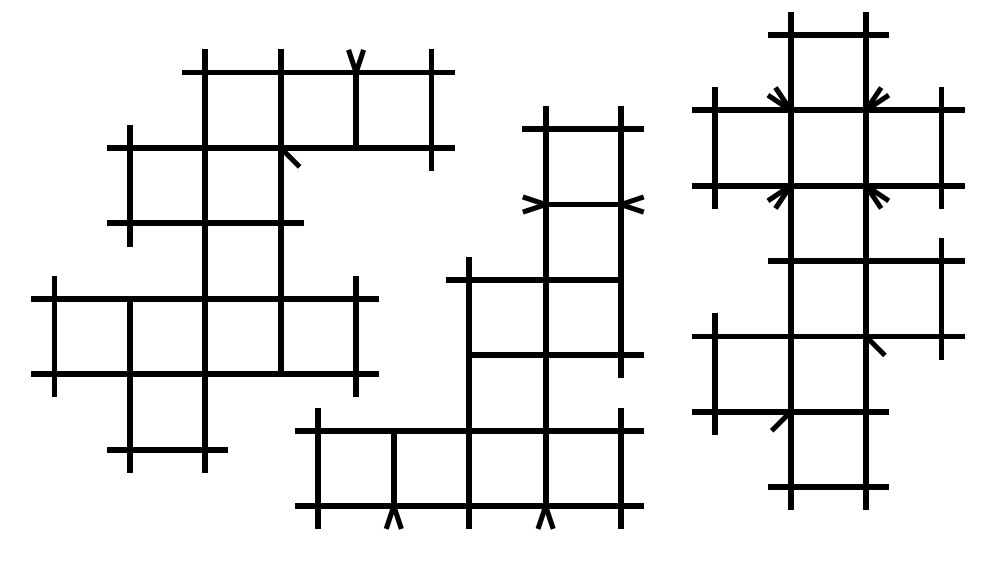

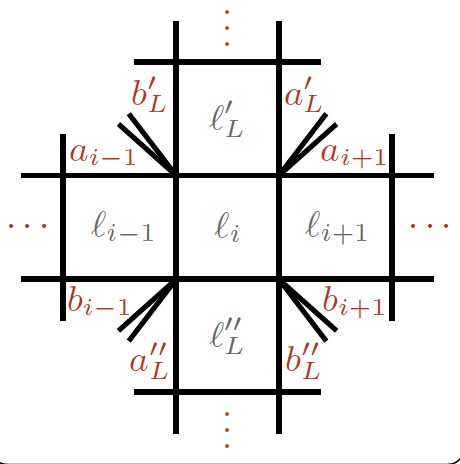

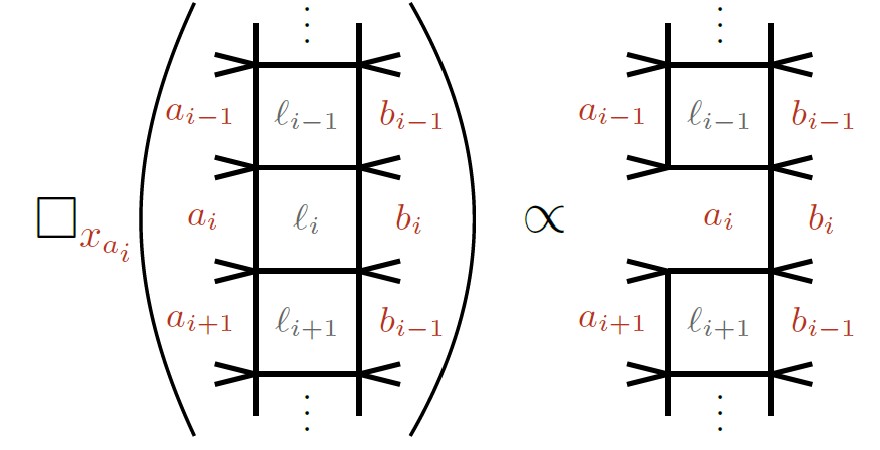

You’ll notice the letters “PTA” showing up again and again here. PTA doesn’t stand for Parent-Teacher Association, but for Pulsar Timing Array. Pulsar timing arrays keep track of pulsars, special neutron stars that spin around, shooting out jets of light. The ones studied by PTAs spin so regularly that we can use them as a kind of cosmic clock, counting time by when their beams hit our telescopes. They’re so regular that, if we see them vary, the best explanation isn’t that their spinning has changed: it’s that space-time itself has.

Because of that, we can use pulsar timing arrays to detect subtle shifts in space and time, ripples in the fabric of the universe caused by enormous gravitational waves. That’s what all these collaborations are for: the Indian Pulsar Timing Array (InPTA), the Chinese Pulsar Timing Array (CPTA), the Parkes Pulsar Timing Array (PPTA), the European Pulsar Timing Array (EPTA), and the North American Nanohertz Observatory for Gravitational Waves (NANOGrav).

For a nice explanation of what they saw, read this twitter thread by Katie Mack, who unlike me is actually an astronomer. NANOGrav, in typical North American fashion, is talking the loudest about it, but in this case they kind of deserve it. They have the most data, fifteen years of measurements, letting them make the clearest case that they are actually seeing evidence of gravitational waves. (And not, as an earlier measurement of theirs saw, Jupiter.)

We’ve seen evidence of gravitational waves before of course, most recently from the gravitational wave observatories LIGO and VIRGO. LIGO and VIRGO could pinpoint their results to colliding black holes and neutrons stars, estimating where they were and how massive. The pulsar timing arrays can’t quite do that yet, even with fifteen years of data. They expect that the waves they are seeing come from colliding black holes as well, but much larger ones: with pulsars spread over a galaxy, the effects they detect are from black holes big enough to be galactic cores. Rather than one at a time, they would see a chorus of many at once, a gravitational wave background (though not to be confused with a cosmic gravitational wave background: this would be from black holes close to the present day, not from the origin of the universe). If it is this background, then they’re seeing a bit more of the super-massive black holes than people expected. But for now, they’re not sure: they can show they’re seeing gravitational waves, but so far not much more.

With that in mind, it’s best to view the result, impressive as it is, as a proof of principle. Much as LIGO showed, not that gravitational waves exist at all, but that it is possible for us to detect them, these pulsar timing arrays have shown that it is possible to detect the gravitational wave background on these vast scales. As the different arrays pool their data and gather more, the technique will become more and more useful. We’ll start learning new things about the life-cycles of black holes and galaxies, about the shape of the universe, and maybe if we’re lucky some fundamental physics too. We’ve opened up a new window, making sure it’s bright enough we can see. Now we can sit back, and watch the universe.