I don’t have a lot to say this week. I’ve been busy moving, in preparation for my new job in the Fall. Moving internationally hasn’t left a lot of time, or mental space, for science, or even for taking a nice photo for this post! But I’ll pick up again next week, with Amplitudes, my sub-field’s big yearly conference.

Category Archives: Misc

What RIBs Could Look Like

The journal Nature recently published an opinion piece about a new concept for science funding called Research Impact Bonds (or RIBs).

Normally, when a government funds something, they can’t be sure it will work. They pay in advance, and have to guess whether a program will do what they expect, or whether a project will finish on time. Impact bonds are a way for them to pay afterwards, so they only pay for projects that actually deliver. Instead, the projects are funded by private investors, who buy “impact bonds” that guarantee them a share of government funding if the project is successful. Here’s an example given in the Nature piece:

For instance, say the Swiss government promises to pay up to one million Swiss francs (US$1.1 million) to service providers that achieve a measurable outcome, such as reducing illiteracy in a certain population by 5%, within a specified number of years. A broker finds one or more service providers that think they can achieve this at a cost of, say, 900,000 francs, as well as investors who agree to pay these costs up front — thus taking on the risk of the project — for a potential 10% gain if successful. If the providers achieve their goals, the government pays 990,000 francs: 900,000 francs for the work and a 90,000-franc investment return. If the project does not succeed, the investors lose their money, but the government does not.

The author of the piece, Michael Hill, thinks that this could be a new way for governments to fund science. In his model, scientists would apply to the government to propose new RIBs. The projects would have to have specific goals and time-frames: “measure the power of this cancer treatment to this accuracy in five years”, for example. If the government thinks the goal is valuable, they commit to paying some amount of money if the goal is reached. Then investors can decide whether the investment is worthwhile. The projects they expect to work get investor money, and if they do end up working the investors get government money. The government only has to pay if the projects work, but the scientists get paid regardless.

Ok, what’s the catch?

One criticism I’ve seen is that this kind of model could only work for very predictable research, maybe even just for applied research. While the author admits RIBs would only be suitable for certain sorts of projects, I think the range is wider than you might think. The project just has to have a measurable goal by a specified end date. Many particle physics experiments work that way: a dark matter detector, for instance, is trying to either rule out or detect dark matter to a certain level of statistical power within a certain run time. Even “discovery” machines, that we build to try to discover the unexpected, usually have this kind of goal: a bigger version of the LHC, for instance, might try to measure the coupling of Higgs bosons to a certain accuracy.

There are a few bigger issues with this model, though. If you go through the math in Hill’s example, you’ll notice that if the project works, the government ends up paying one million Swiss francs for a service that only cost the provider 900,000 Swiss francs. Under a normal system, the government would only have had to pay 900,000. This gets compensated by the fact that not every project works, so the government only pays for some projects and not others. But investors will be aware of this, and that means the government can’t offer too many unrealistic RIBs: the greater the risk investors are going to take, the more return they’ll expect. On average then, the government would have to pay about as much as they would normally: the cost of the projects that succeed, plus enough money to cover the risk that some fail. (In fact, they’d probably pay a bit more, to give the investors a return on the investment.)

So the government typically won’t save money, at least not if they want to fund the same amount of research. Instead, the idea is that they will avoid risk. But it’s not at all clear to me that the type of risk they avoid is one they want to.

RIBs might appeal to voters: it might sound only fair that a government only funds the research that actually works. That’s not really a problem for the government itself, though: because governments usually pay for many small projects, they still get roughly as much success overall as they want, they just don’t get to pick where. Instead, RIBS put the government agency in a much bigger risk, the risk of unexpected success. As part of offering RIBs, the government would have to estimate how much money they would be able to pay when the projects end. They would want to fund enough projects so that, on average, they pay that amount of money. (Otherwise, they’d end up funding science much less than they do now!) But if the projects work out better than expected, then they’d have to pay much more than they planned. And government science agencies usually can’t do this. In many countries, they can’t plan far in advance at all: their budgets get decided by legislators year to year, and delays in decisions mean delays in funding. If an agency offered RIBs that were more successful than expected, they’d either have to cut funding somewhere else (probably firing a lot of people), or just default on their RIBs, weakening the concept for the next time they used them. These risks, unlike the risk of individual experiments not working, are risks that can really hurt government agencies.

Impact bonds typically have another advantage, in that they spread out decision-making. The Swiss government in Hill’s example doesn’t have to figure out which service providers can increase literacy, or how much it will cost them: it just puts up a budget, and lets investors and service providers figure out if they can make it work. This also serves as a hedge against corruption. If the government made the decisions, they might distribute funding for unrelated political reasons or even out of straight-up bribery. They’d also have to pay evaluators to figure things out. Investors won’t take bribes to lose money, so in theory would be better at choosing projects that will actually work, and would have a vested interest in paying for a good investigation.

This advantage doesn’t apply to Hill’s model of RIBs, though. In Hill’s model, scientists still need to apply to the government to decide which of their projects get offered as RIBs, so the government still needs to decide which projects are worth investing in. Then the scientists or the government need to take another step, and convince investors. The scientists in this equation effectively have to apply twice, which anyone who has applied for a government grant will realize is quite a lot of extra time and effort.

So overall, I don’t think Hills’ model of RIBs is useful, even for the purpose he imagines. It’s too risky for government science agencies to commit to payments like that, and it generates more, not less, work for scientists and the agency.

Hill’s model, though, isn’t the only way RIBs can work. And “avoiding risk” isn’t the only reason we might want them. There are two other reasons one might want RIBs, with very different-sounding motivations.

First, you might be pessimistic about mainstream science. Maybe you think scientists are making bad decisions, choosing ideas that either won’t pan out or won’t have sufficient impact, based more on fashion than on careful thought. You want to incentivize them to do better, to try to work out what impact they might have with some actual numbers and stand by their judgement. If that’s your perspective, you might be interested in RIBs for the same reason other people are interested in prediction markets: by getting investors involved, you have people willing to pay for an accurate estimate.

Second, you might instead be optimistic about mainstream science. You think scientists are doing great work, work that could have an enormous impact, but they don’t get to “capture that value”. Some projects might be essential to important, well-funded goals, but languish unrewarded. Others won’t see their value until long in the future, or will do so in unexpected ways. If scientists could fund projects based on their future impact, with RIBs, maybe they could fund more of this kind of work.

(I first started thinking about this perspective due to a talk by Sabrina Pasterski. The talk itself offended a lot of people, and had some pretty impractical ideas, like selling NFTs of important physics papers. But I think one part of the perspective, that scientists have more impact than we think, is worth holding on to.)

If you have either of those motivations, Hill’s model won’t help. But another kind of model perhaps could. Unlike Hill’s, it could fund much more speculative research, ideas where we don’t know the impact until decades down the line. To demonstrate, I’ll show how it could fund some very speculative research: the work of Peter van Nieuwenhuizen.

Peter van Nieuwenhuizen is one of the pioneers of the theory of supergravity, a theory that augments gravity with supersymmetric partner particles. From its beginnings in the 1970’s, the theory ended up having a major impact on string theory, and today they are largely thought of as part of the same picture of how the universe might work.

His work has, over time, had more practical consequences though. In the 2000’s, researchers working with supergravity noticed a calculational shortcut: they could do a complicated supergravity calculation as the “square” of a much simpler calculation in another theory, called Yang-Mills. Over time, they realized the shortcut worked not just for supergravity, but for ordinary gravity as well, and not just for particle physics calculations but for gravitational wave calculations. Now, their method may make an important contribution to calculations for future gravitational wave telescopes like the Einstein telescope, letting them measure properties of neutron stars.

With that in mind, imagine the following:

In 1967, Jocelyn Bell Burnell and Antony Hewish detected a pulsar, in one of the first direct pieces of evidence for the existence of neutron stars. Suppose that in the early 1970’s NASA decided to announce a future purchase of RIBs: in 2050, they would pay a certain amount to whoever was responsible for finding the equation of state of a neutron star, the formula that describes how its matter moves under pressure. They compute based on estimates of economic growth and inflation, and arrive at some suitably substantial number.

At the same time, but unrelatedly, van Nieuwenhuizen and collaborators sell RIBs. Maybe they use the proceeds to buy more computer time for their calculations, or to refund travel so they can more easily meet and discuss. They tell the buyers that, if some government later decides to reward their discoveries, the holders of the RIB would get a predetermined cut of the rewards.

The years roll by, and barring some unexpected medical advances the discoverers of supergravity die. In the meantime, researchers use their discovery to figure out how to make accurate predictions of gravitational waves from merging neutron stars. When the Einstein telescope turns out, it detects such a merger, and the accurate predictions let them compute the neutron star’s equation of state.

In 2050, then, NASA looks back. They make a list of everyone who contributed to the discovery of the neutron star’s equation of state, every result that was needed for the discovery, and try to estimate how important each contribution was. Then they spend the money they promised buying RIBs, up to the value for each contributor. This includes RIBs originally held by the investors in van Nieuwenhuizen and collaborators. Their current holders make some money, justifying whatever value they paid from their previous owners.

Imagine a world in which government agencies do this kind of thing all the time. Scientists could sell RIBs in their projects, without knowing exactly which agency would ultimately pay for them. Rather than long grant applications, they could write short summaries for investors, guessing at the range of their potential impact, and it would be up to the investors to decide whether the estimate made sense. Scientists could get some of the value of their discoveries, even when that value is quite unpredictable. And they would be incentivized to pick discoveries that could have high impact, and to put a bit of thought and math into what kind of impact that could be.

(Should I still be calling these things bonds, when the buyers don’t know how much they’ll be worth at the end? Probably not. These are more like research impact shares, on a research impact stock market.)

Are there problems with this model, then? Oh sure, loads!

I already mentioned that it’s hard for government agencies to commit to spending money five years down the line. A seventy-year commitment, from that perspective, sounds completely ridiculous.

But we don’t actually need that in the model. All we need is a good reason for investors to think that, eventually, NASA will buy some research impact shares. If government agencies do this regularly, then they would have that reason. They could buy a variety of theoretical developments, a diversified pool to make it more likely some government agency would reward them. This version of the model would be riskier, though, so they’d want more return in exchange.

Another problem is the decision-making aspect. Government agencies wouldn’t have to predict the future, but they would have to accurately assess the past, fairly estimating who contributed to a project, and they would have to do it predictably enough that it could give rise to worthwhile investments. This is itself both controversial and a lot of work. If we figure out the neutron star equation of state, I’m not sure I trust NASA to reward van Nieuwenhuizen’s contribution to it.

This leads to the last modification of the model, and the most speculative one. Over time, government agencies will get better and better at assigning credit. Maybe they’ll have better models of how scientific progress works, maybe they’ll even have advanced AI. A future government (or benevolent AI, if you’re into that) might decide to buy research impact shares in order to validate important past work.

If you believe that might happen, then you don’t need a track record of government agencies buying research impact shares. As a scientist, you can find a sufficiently futuristically inclined investor, and tell them this story. You can sell them some shares, and tell them that, when the AI comes, they will have the right to whatever benefit it bestows upon your research.

I could imagine some people doing this. If you have an image of your work saving humanity in the distant future, you should be able to use that image to sell something to investors. It would be insanely speculative, a giant pile of what-ifs with no guarantee of any of it cashing out. But at least it’s better than NFTs.

Reader Poll: Considering a Move to Substack

This blog is currently hosted on a site called WordPress.com. When I started the blog, I picked WordPress mostly just because it was easy and free. (Since then I started paying them money, both to remove ads and to get a custom domain, 4gravitons.com.)

Now, the blog is more popular, and you guys access it in a wide variety of ways. 333 of you are other users of WordPress.com: WordPress has a “Reader” tab that lets users follow other blogs through the site. (I use that tab to keep up with a few of the blogs in my Blogroll.) 258 of you instead get a weekly email: this is a service WordPress.com offers, letting people sign up by email to the blog. Others follow on social media: on Twitter, Facebook, and Tumblr.

(Are there other options? If someone’s figured out how to follow with an RSS feed, or wants me to change something so they can do that, let me know in the comments!)

Recently, I’ve gotten a bit annoyed with the emails WordPress sends out. The problem is that they don’t seem to handle images in a sensible way: I can scale an image to fit in a blog post, but in the email the image is always full-size, sometimes taking up the entire screen.

Last year, someone reached out to me from Substack.com, trying to recruit me to switch to their site. Substack is a (increasingly popular) blogging platform, focused on email newsletters. The whole site is built around the idea that posts are emailed to subscribers, with a simplified layout that makes that feasible and consistent. Like WordPress, they have a system where people can follow the blog through a Substack account, and the impression I get is that a lot of people use it, browsing topics they find interesting.

(Substack also has a system for paid subscribers. That isn’t mandatory, and partly due to recent events I’m not expecting to use it.)

Since Substack is built for emails, I’m guessing it would solve the issue I’ve been having with images. It would also let more people discover the blog via the Substack app. On the other hand, Substack allows a lot less customization. I wouldn’t be able to have the cute pull-down menus from the top of the blog, or the Feynman diagram background. I don’t think I could have the Tag cloud or the Categories filter.

Most importantly, though, I don’t want to lose long-term readers. I don’t know if some of you would have more trouble accessing Substack than WordPress, or if some really prefer to follow here.

One option is that I use both sites, at least for a bit. There are services built for cross-posting, that let a post on Substack automatically get posted on WordPress as well. I might do that temporarily (to make sure everyone has enough warning to transfer) or permanently (if there are people who really would never use Substack).

(I also might end up making an institutional web page with some of the useful educational guides, once I’ve got a permanent job. That could cover some features that Substack can’t.)

I wanted to do a couple polls, to get a feeling for your opinions. The first is a direct yes or no: do you prefer I stay at WordPress, prefer I switch to Substack, or don’t care either way. (For example, if you follow me via Facebook, you’ll get a link every week regardless.) The second poll asks about more detailed concerns, and you can pick as many entries as you want to give me a feeling for what matters to you. Please, if you read the blog at all regularly, fill out both polls: I want to know what you think!

Traveling This Week

I’m traveling this week, so this will just be a short post. This isn’t a scientific trip exactly: I’m in Poland, at an event connected to the 550th anniversary of the birth of Copernicus.

Part of this event involved visiting the Copernicus Science Center, the local children’s science museum. The place was sold out completely. For any tired science communicators, I recommend going to a sold-out science museum: the sheer enthusiasm you’ll find there is balm for the most jaded soul.

AI Is the Wrong Sci-Fi Metaphor

Over the last year, some people felt like they were living in a science fiction novel. Last November, the research laboratory OpenAI released ChatGPT, a program that can answer questions on a wide variety of topics. Last month, they announced GPT-4, a more powerful version of ChatGPT’s underlying program. Already in February, Microsoft used GPT-4 to add a chatbot feature to its search engine Bing, which journalists quickly managed to use to spin tales of murder and mayhem.

For those who have been following these developments, things don’t feel quite so sudden. Already in 2019, AI Dungeon showed off how an early version of GPT could be used to mimic an old-school text-adventure game, and a tumblr blogger built a bot that imitates his posts as a fun side project. Still, the newer programs have shown some impressive capabilities.

Are we close to “real AI”, to artificial minds like the positronic brains in Isaac Asimov’s I, Robot? I can’t say, in part because I’m not sure what “real AI” really means. But if you want to understand where things like ChatGPT come from, how they work and why they can do what they do, then all the talk of AI won’t be helpful. Instead, you need to think of an entirely different set of Asimov novels: the Foundation series.

While Asimov’s more famous I, Robot focused on the science of artificial minds, the Foundation series is based on a different fictional science, the science of psychohistory. In the stories, psychohistory is a kind of futuristic social science. In the real world, historians and sociologists can find general principles of how people act, but don’t yet have the kind of predictive theories physicists or chemists do. Foundation imagines a future where powerful statistical methods have allowed psychohistorians to precisely predict human behavior: not yet that of individual people, but at least the average behavior of civilizations. They can not only guess when an empire is soon to fall, but calculate how long it will be before another empire rises, something few responsible social scientists would pretend to do today.

GPT and similar programs aren’t built to predict the course of history, but they do predict something: given part of a text, they try to predict the rest. They’re called Large Language Models, or LLMs for short. They’re “models” in the sense of mathematical models, formulas that let us use data to make predictions about the world, and the part of the world they model is our use of language.

Normally, a mathematical model is designed based on how we think the real world works. A mathematical model of a pandemic, for example, might use a list of people, each one labeled as infected or not. It could include an unknown number, called a parameter, for the chance that one person infects another. That parameter would then be filled in, or fixed, based on observations of the pandemic in the real world.

LLMs (as well as most of the rest of what people call “AI” these days) are a bit different. Their models aren’t based on what we expect about the real world. Instead, they’re in some sense “generic”, models that could in principle describe just about anything. In order to make this work, they have a lot more parameters, tons and tons of flexible numbers that can get fixed in different ways based on data.

(If that part makes you a bit uncomfortable, it bothers me too, though I’ve mostly made my peace with it.)

The surprising thing is that this works, and works surprisingly well. Just as psychohistory from the Foundation novels can predict events with much more detail than today’s historians and sociologists, LLMs can predict what a text will look like much more precisely than today’s literature professors. That isn’t necessarily because LLMs are “intelligent”, or because they’re “copying” things people have written. It’s because they’re mathematical models, built by statistically analyzing a giant pile of texts.

Just as Asimov’s psychohistory can’t predict the behavior of individual people, LLMs can’t predict the behavior of individual texts. If you start writing something, you shouldn’t expect an LLM to predict exactly how you would finish. Instead, LLMs predict what, on average, the rest of the text would look like. They give a plausible answer, one of many, for what might come next.

They can’t do that perfectly, but doing it imperfectly is enough to do quite a lot. It’s why they can be used to make chatbots, by predicting how someone might plausibly respond in a conversation. It’s why they can write fiction, or ads, or college essays, by predicting a plausible response to a book jacket or ad copy or essay prompt.

LLMs like GPT were invented by computer scientists, not social scientists or literature professors. Because of that, they get described as part of progress towards artificial intelligence, not as progress in social science. But if you want to understand what ChatGPT is right now, and how it works, then that perspective won’t be helpful. You need to put down your copy of I, Robot and pick up Foundation. You’ll still be impressed, but you’ll have a clearer idea of what could come next.

Valentine’s Day Physics Poem 2023

Since Valentine’s Day was this week, it’s time for the next installment of my traditional Valentine’s Day Physics Poems. New readers, don’t let this drive you off, I only do it once a year! And if you actually like it, you can take a look at poems from previous years here.

Married to a Model

If you ever face a physics class distracted, Rappers and footballers twinkling on their phones, Then like an awkward youth pastor, interject, “You know who else is married to a Model?” Her name is Standard, you see, Wife of fifty years to Old Man Physics, Known for her beauty, charm, and strangeness too. But Old Man Physics has a wandering eye, and dreams of Models Beyond. Let the old man bend your ear, you’ll hear a litany of Problems. He’ll never understand her, so he starts. Some matters she holds weighty, some feather-light with nary rhyme or reason (which he is owed, he’s sure). She’s unnatural, he says, (echoing Higgins et al.), a set of rules he can’t predict. (But with those rules, all else is possible.) Some regularities she holds to fast, despite room for exception, others breaks, like an ill-lucked bathroom mirror. And then, he says, she’ll just blow up (when taken to extremes), while singing nonsense in the face of Gravity. He’s been keeping a careful eye and noticing anomalies (and each time, confronting them, finds an innocent explanation, but no matter). And he imagines others with yet wilder curves and more sensitive reactions (and nonsense, of course, that he’s lived fifty years without). Old man physics talks, that’s certain. But beyond the talk, beyond the phases and phrases, (conscious uncoupling, non-empirical science), he stays by her side. He knows Truth, in this world, is worth fighting for.

Chaos: Warhammer 40k or Physics?

As I mentioned last week, it’s only natural to confuse chaos theory in physics with the forces of chaos in the game Warhammer 40,000. Since it will be Halloween in a few days, it’s a perfect time to explain the subtle differences between the two.

| Warhammer 40k | physics |

|---|---|

| In the grim darkness of the far future, there is only war! | In the grim darkness of Chapter 11 of Goldstein, Poole, and Safko, there is only Chaos! |

| Birthed from the psychic power of mortal minds | Birthed from the numerical computations of mortal physicists |

| Ruled by four chaos gods: Khorne, Tzeench, Nurgle, and Slaanesh | Ruled by three principles: sensitivity to initial conditions, topological transitivity, and dense periodic orbits |

| In the 31st millennium, nine legions of space marines leave humanity due to the forces of chaos | In the 3.5 millionth millennium, Mercury leaves the solar system due to the force of gravity |

| While events may appear unpredictable, everything is determined by Tzeench’s plans | While events may appear unpredictable, everything is determined by the initial conditions |

| Humans drawn to strangely attractive cults | Systems in phase space drawn to strange attractors |

| Over time, cultists mutate, governed by the warp | Over time, trajectories diverge, governed by the Lyapunov exponent |

| To resist chaos, the Imperium of Man demands strict spiritual control | To resist chaos, the KAM Theorem demands strict mathematical conditions |

| Inspires nerds to paint detailed miniatures | Inspires nerds to stick pendulums together |

| Fantasy version with confusing relation to the original | Quantum version with confusing relation to the original |

| Lots of cool gothic art | Pretty fractals |

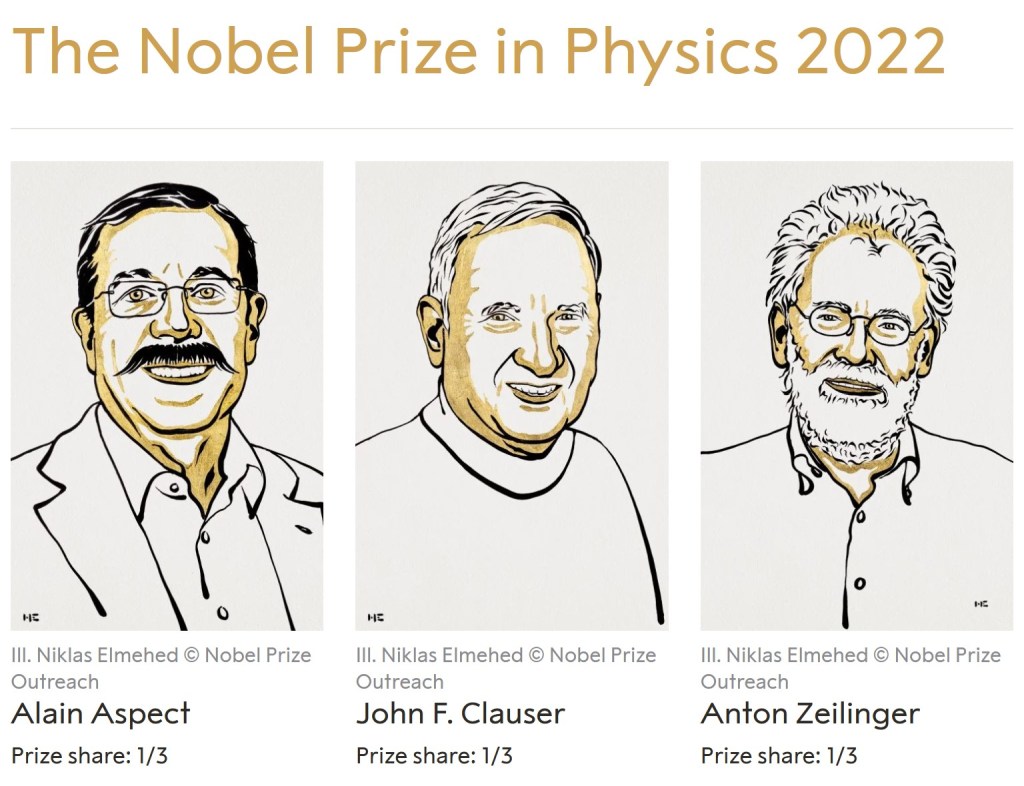

Congratulations to Alain Aspect, John F. Clauser and Anton Zeilinger!

The 2022 Nobel Prize was announced this week, awarded to Alain Aspect, John F. Clauser, and Anton Zeilinger for experiments with entangled photons, establishing the violation of Bell inequalities and pioneering quantum information science.

I’ve complained in the past about the Nobel prize awarding to “baskets” of loosely related topics. This year, though, the three Nobelists have a clear link: they were pioneers in investigating and using quantum entanglement.

You can think of a quantum particle like a coin frozen in mid-air. Once measured, the coin falls, and you read it as heads or tails, but before then the coin is neither, with equal chance to be one or the other. In this metaphor, quantum entanglement slices the coin in half. Slice a coin in half on a table, and its halves will either both show heads, or both tails. Slice our “frozen coin” in mid-air, and it keeps this property: the halves, both still “frozen”, can later be measured as both heads, or both tails. Even if you separate them, the outcomes never become independent: you will never find one half-coin to land on tails, and the other on heads.

Einstein thought that this couldn’t be the whole story. He was bothered by the way that measuring a “frozen” coin seems to change its behavior faster than light, screwing up his theory of special relativity. Entanglement, with its ability to separate halves of a coin as far as you liked, just made the problem worse. He thought that there must be a deeper theory, one with “hidden variables” that determined whether the halves would be heads or tails before they were separated.

In 1964, a theoretical physicist named J.S. Bell found that Einstein’s idea had testable consequences. He wrote down a set of statistical equations, called Bell inequalities, that have to hold if there are hidden variables of the type Einstein imagined, then showed that quantum mechanics could violate those inequalities.

Bell’s inequalities were just theory, though, until this year’s Nobelists arrived to test them. Clauser was first: in the 70’s, he proposed a variant of Bell’s inequalities, then tested them by measuring members of a pair of entangled photons in two different places. He found complete agreement with quantum mechanics.

Still, there was a loophole left for Einstein’s idea. If the settings on the two measurement devices could influence the pair of photons when they were first entangled, that would allow hidden variables to influence the outcome in a way that avoided Bell and Clauser’s calculations. It was Aspect, in the 80’s, who closed this loophole: by doing experiments fast enough to change the measurement settings after the photons were entangled, he could show that the settings could not possibly influence the forming of the entangled pair.

Aspect’s experiments, in many minds, were the end of the story. They were the ones emphasized in the textbooks when I studied quantum mechanics in school.

The remaining loopholes are trickier. Some hope for a way to correlate the behavior of particles and measurement devices that doesn’t run afoul of Aspect’s experiment. This idea, called, superdeterminism, has recently had a few passionate advocates, but speaking personally I’m still confused as to how it’s supposed to work. Others want to jettison special relativity altogether. This would not only involve measurements influencing each other faster than light, but also would break a kind of symmetry present in the experiments, because it would declare one measurement or the other to have happened “first”, something special relativity forbids. The majority, uncomfortable with either approach, thinks that quantum mechanics is complete, with no deterministic theory that can replace it. They differ only on how to describe, or interpret, the theory, a debate more the domain of careful philosophy than of physics.

After all of these philosophical debates over the nature of reality, you may ask what quantum entanglement can do for you?

Suppose you want to make a computer out of quantum particles, one that uses the power of quantum mechanics to do things no ordinary computer can. A normal computer needs to copy data from place to place, from hard disk to RAM to your processor. Quantum particles, however, can’t be copied: a theorem says that you cannot make an identical, independent copy of a quantum particle. Moving quantum data then required a new method, pioneered by Anton Zeilinger in the late 90’s using quantum entanglement. The method destroys the original particle to make a new one elsewhere, which led to it being called quantum teleportation after the Star Trek devices that do the same with human beings. Quantum teleportation can’t move information faster than light (there’s a reason the inventor of Le Guin’s ansible despairs of the materialism of “Terran physics”), but it is still a crucial technology for quantum computers, one that will be more and more relevant as time goes on.

Things Which Are Fluids

For overambitious apes like us, adding integers is the easiest thing in the world. Take one berry, add another, and you have two. Each remains separate, you can lay them in a row and count them one by one, each distinct thing adding up to a group of distinct things.

Other things in math are less like berries. Add two real numbers, like pi and the square root of two, and you get another real number, bigger than the first two, something you can write in an infinite messy decimal. You know in principle you can separate it out again (subtract pi, get the square root of two), but you can’t just stare at it and see the parts. This is less like adding berries, and more like adding fluids. Pour some water in to some other water, and you certainly have more water. You don’t have “two waters”, though, and you can’t tell which part started as which.

Some things in math look like berries, but are really like fluids. Take a polynomial, say . It looks like three types of things, like three berries: five

, six

, and eight

. Add another polynomial, and the illusion continues: add

and you get

. You’ve just added more

, more

, more

, like adding more strawberries, blueberries, and raspberries.

But those berries were a choice you made, and not the only one. You can rewrite that first polynomial, for example saying . That’s the same thing, you can check. But now it looks like five

, negative four

, and seven

. It’s different numbers of different things, blackberries or gooseberries or something. And you can do this in many ways, infinitely many in fact. The polynomial isn’t really a collection of berries, for all it looked like one. It’s much more like a fluid, a big sloshing mess you can pour into buckets of different sizes. (Technically, it’s a vector space. Your berries were a basis.)

Even smart, advanced students can get tripped up on this. You can be used to treating polynomials as a fluid, and forget that directions in space are a fluid, one you can rotate as you please. If you’re used to directions in space, you’ll get tripped up by something else. You’ll find that types of particles can be more fluid than berry, the question of which quark is which not as simple as how many strawberries and blueberries you have. The laws of physics themselves are much more like a fluid, which should make sense if you take a moment, because they are made of equations, and equations are like a fluid.

So my fellow overambitious apes, do be careful. Not many things are like berries in the end. A whole lot are like fluids.

Valentine’s Day Physics Poem 2022

Monday is Valentine’s Day, so I’m following my yearly tradition and posting a poem about love and physics. If you like it, be sure to check out my poems from past years here.

Time Crystals

A physicist once dreamed

of a life like a crystal.

Each facet the same, again and again,

effortlessly

until the end of time.

This is, of course, impossible.

A physicist once dreamed

of a life like a crystal.

Each facet the same, again and again,

not effortlessly,

but driven,

with reliable effort

input energy

(what the young physicists call work).

This, (you might say of course,) is possible.

It means more than you’d think.

A thing we model as a spring

(or: anyone and anything)

has a restoring force:

a force to pull it back

a force to keep it going.

A thing we model as a spring

(yes you and me and everything)

has a damping force, too:

this slows it down

and tires it out.

The dismal law

of finite life.

The driving force is another thing

no mere possession of the spring.

The driving force comes from

o u t s i d e

and breaks the rules.

Your rude “of course”:

a sign you guess

a simple resolution.

That outside helpmeet,

doing work,

will be used up,

drained,

fueling that crystal life.

But no.

That was the discovery.

No net drain,

but back and forth,

each feeding the other.

With this alone

(and only this)

the system breaks the dismal law

and lives forever.

(As a child, did you ever sing,

of giving away, and giving away,

and only having more?)

A physicist dreamed,

alone, impossibly,

of a life like a crystal.

Collaboration made it real.