For Halloween, this blog has a tradition of covering “the spooky side” of physics. This year, I’m bringing in a concept from biology to ask a spooky physics “what if?”

In the 1950’s, biologists discovered that birds were susceptible to a worryingly effective trick. By giving them artificial eggs larger and brighter than their actual babies, they found that the birds focused on the new eggs to the exclusion of their own. They couldn’t help trying to hatch the fake eggs, even if they were so large that they would fall off when they tried to sit on them. The effect, since observed in other species, became known as a supernormal stimulus, or superstimulus.

Can this happen to humans? Some think so. They worry about junk food we crave more than actual nutrients, or social media that eclipses our real relationships. Naturally, this idea inspires horror writers, who write about haunting music you can’t stop listening to, or holes in a wall that “fit” so well you’re compelled to climb in.

(And yes, it shows up in porn as well.)

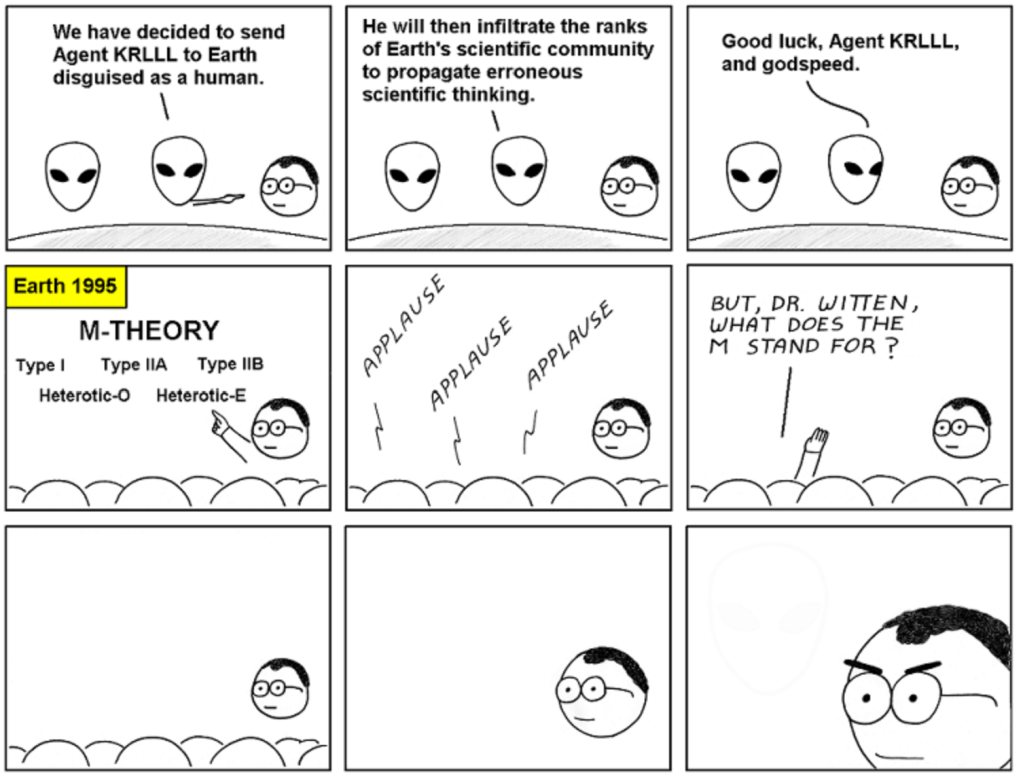

But this is a physics blog, not a biology blog. What kind of superstimulus would work on physicists?

Well for one, this sounds a lot like some criticisms of string theory. Instead of a theory that just unifies some forces, why not unify all the forces? Instead of just learning some advanced mathematics, why not learn more, and more? And if you can’t be falsified by any experiment, well, all that would do is spoil the fun, right?

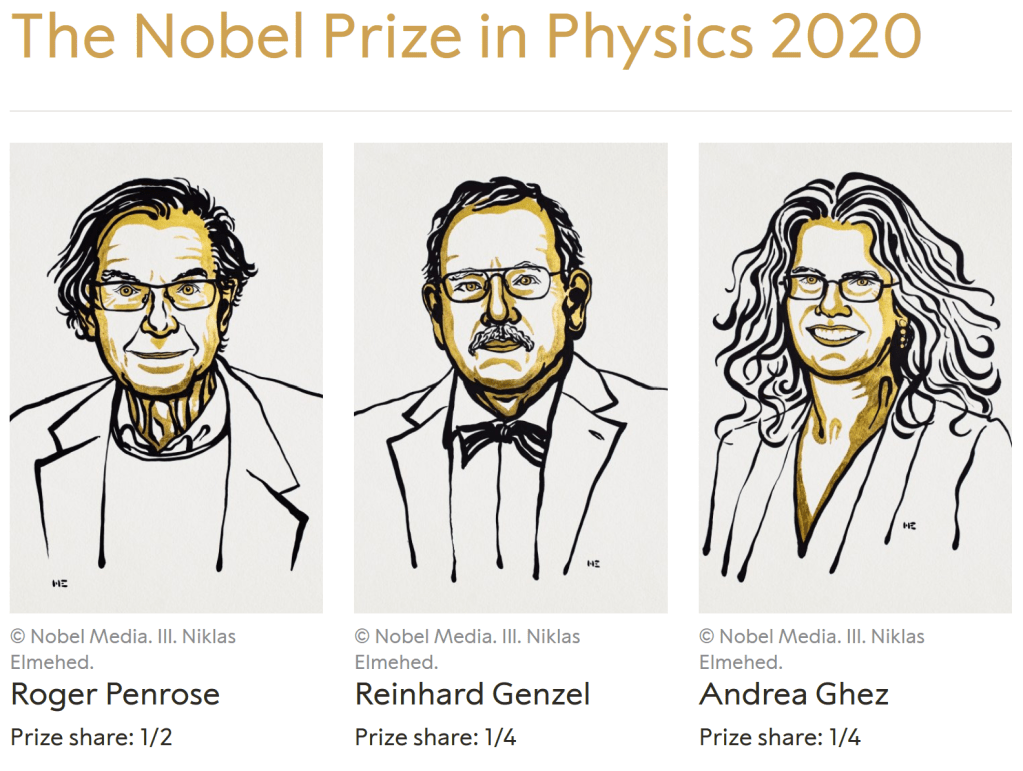

But it’s not just string theory you could apply this logic to. Astrophysicists study not just one world but many. Cosmologists study the birth and death of the entire universe. Particle physicists study the fundamental pieces that make up the fundamental pieces. We all partake in the euphoria of problem-solving, a perpetual rush where each solution leads to yet another question.

Do I actually think that string theory is a superstimulus, that astrophysics or particle physics is a superstimulus? In a word, no. Much as it might look that way from the news coverage, most physicists don’t work on these big, flashy questions. Far from being lured in by irresistible super-scale problems, most physicists work with tabletop experiments and useful materials. For those of us who do look up at the sky or down at the roots of the world, we do it not just because it’s compelling but because it has a good track record: physics wouldn’t exist if Newton hadn’t cared about the orbits of the planets. We study extremes because they advance our understanding of everything else, because they give us steam engines and transistors and change everyone’s lives for the better.

Then again, if I had fallen victim to a superstimulus, I’d say that anyway, right?

*cue spooky music*