Perimeter is hosting this year’s Mathematica Summer School on Theoretical Physics. The school is a mix of lectures on a topic in physics (this year, the phenomenon of quantum entanglement) and tips and tricks for using the symbolic calculation program Mathematica.

Juan Maldacena is one of the lecturers, which gave me a chance to hear his Romeo and Juliet-based explanation of the properties of wormholes. While I’ve criticized some of Maldacena’s science popularization work in the past, this one is pretty solid, so I thought I’d share it with you guys.

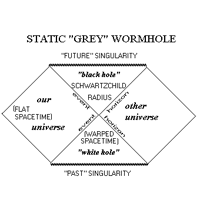

You probably think of wormholes as “shortcuts” to travel between two widely separated places. As it turns out, this isn’t really accurate: while “normal” wormholes do connect distant locations, they don’t do it in a way that allows astronauts to travel between them, Interstellar-style. This can be illustrated with something called a Penrose diagram:

In the traditional Penrose diagram, time goes upward, while space goes from side to side. In order to measure both in the same units, we use the speed of light, so one year on the time axis corresponds to one light-year on the space axis. This means that if you’re traveling at a 45 degree line on the diagram, you’re going at the speed of light. Any lower angle is impossible, while any higher angle means you’re going slower.

If we start in “our universe” in the diagram, can we get to the “other universe”?

Pretty clearly, the answer is no. As long as we go slower than the speed of light, when we pass the event horizon of the wormhole we will end up, not in the “other universe”, but at the part of the diagram labeled Future Singularity, the singularity at the center of the black hole. Even going at the speed of light only keeps us orbiting the event horizon for all eternity, at best.

What use could such a wormhole be? Well, imagine you’re Romeo or Juliet.

Romeo has been banished from Verona, but he took one end of a wormhole with him, while the other end was left with Juliet. He can’t go through and visit her, she can’t go through and visit him. But if they’re already considering taking poison, there’s an easier way. If they both jump in to the wormhole, they’ll fall in to the singularity. Crucially, though, it’s the same singularity, so once they’re past the event horizon they can meet inside the black hole, spending some time together before the end.

This explains what wormholes really are: two black holes that share a center.

Why was Maldacena talking about this at a school on entanglement? Maldacena has recently conjectured that quantum entanglement and wormholes are two sides of the same phenomenon, that pairs of entangled particles are actually connected by wormholes. Crucially, these wormholes need to have the properties described above: you can’t use a pair of entangled particles to communicate information faster than light, and you can’t use a wormhole to travel faster than light. However, it is the “shared” singularity that ends up particularly useful, as it suggests a solution to the problem of black hole firewalls.

Firewalls were originally proposed as a way of getting around a particular paradox relating three states connected by quantum entanglement: a particle inside a black hole, radiation just outside the black hole, and radiation far away from the black hole. The way the paradox is set up, it appears that these three states must all be connected. As it turns out, though, this is prohibited by quantum mechanics, which only allows two states to be entangled at a time. The original solution proposed for this was a “firewall”, a situation in which anyone trying to observe all three states would “burn up” when crossing the event horizon, thus avoiding any observed contradiction. Maldacena’s conjecture suggests another way: if someone interacts with the far-away radiation, they have an effect on the black hole’s interior, because the two are connected by a wormhole! This ends up getting rid of the contradiction, allowing the observer to view the black hole and distant radiation as two different descriptions of the same state, and it depends crucially on the fact that a wormhole involves a shared singularity.

There’s still a lot of detail to be worked out, part of the reason why Maldacena presented this research here was to inspire more investigation from students. But it does seem encouraging that Romeo and Juliet might not have to face a wall of fire before being reunited.