Did you hear about the asteroid?

Which one?

You might have heard that an asteroid named 2024 YR4 is going to come unusually close to the Earth in 2032. When it first made the news, astronomers estimated a non-negligible chance of it hitting us: about three percent. That’s small enough that they didn’t expect it to happen, but large enough to plan around it: people invest in startups with a smaller chance of succeeding. Still, people were fairly calm about this one, and there are a couple of good reasons:

- First, this isn’t a “kill the dinosaurs” asteroid, it’s much smaller. This is a “Tunguska Event” asteroid. Still pretty bad if it happens near a populated area, but not the end of life as we know it.

- We know about it far in advance, and space agencies have successfully deflected an asteroid before, for a test. If it did pose a risk, it’s quite likely they’d be able to change its path so it misses the Earth instead.

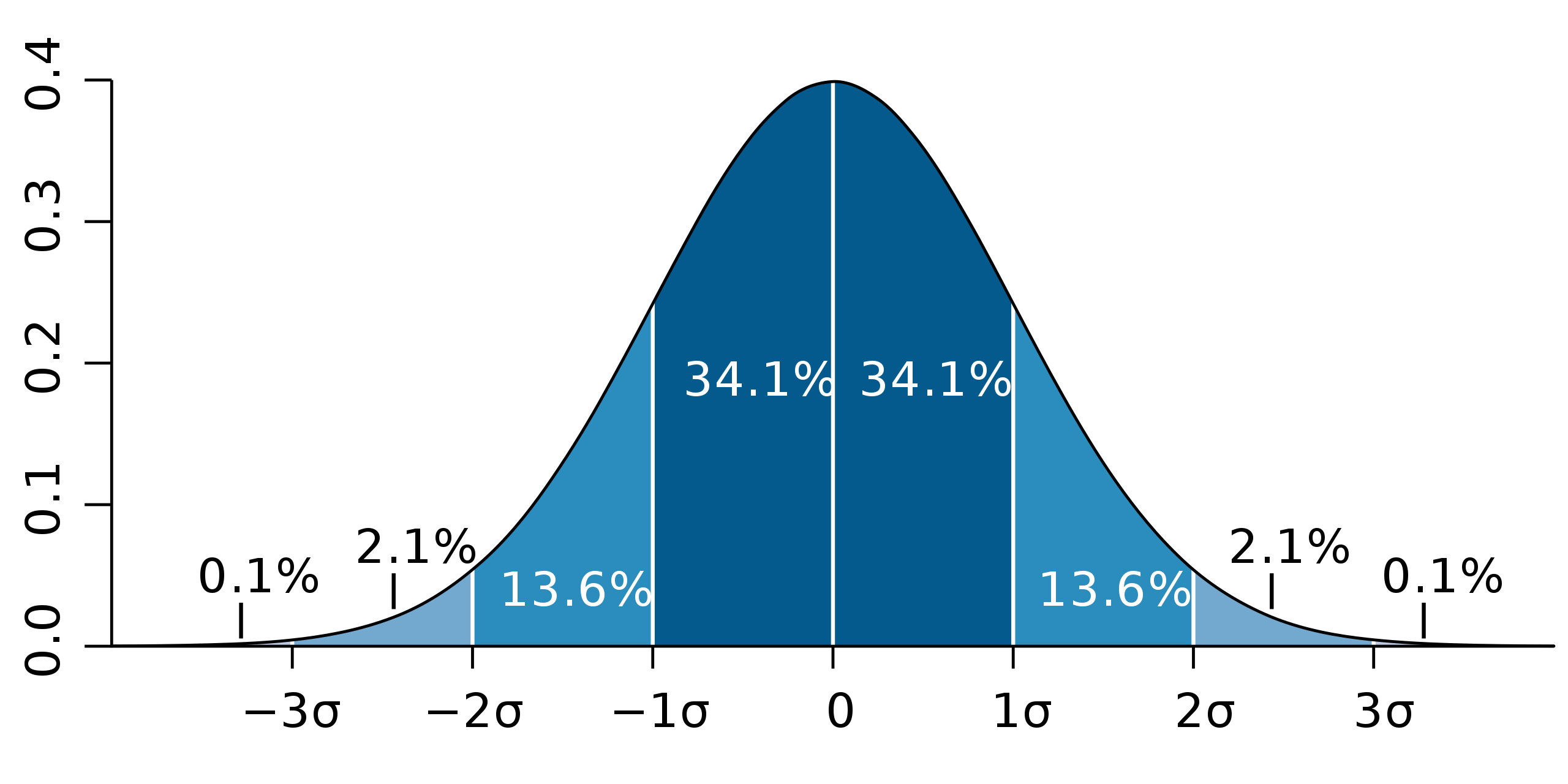

- It’s tempting to think of that 3% chance as like a roll of a hundred-sided die: the asteroid is on a random path, roll 1 to 3 and it will hit the Earth, roll higher and it won’t, and nothing we do will change that. In reality, though, that 3% was a measure of our ignorance. As astronomers measure the asteroid more thoroughly, they’ll know more and more about its path, and each time they figure something out, they’ll update the number.

And indeed, the number has been updated. In just the last few weeks, the estimated probability of impact has dropped from 3% to a few thousandths of a percent, as more precise observations clarified the asteroid’s path. There’s still a non-negligible chance it will hit the moon (about two percent at the moment), but it’s far too small to do more than make a big flashy crater.

It’s kind of fun to think that there are people out there who systematically track these things, with a plan to deal with them. It feels like something out of a sci-fi novel.

But I find the other asteroid more fun.

In 2020, a probe sent by NASA visited an asteroid named Bennu, taking samples which it carefully packaged and brought back to Earth. Now, scientists have analyzed the samples, revealing several moderately complex chemicals that have an important role in life on Earth, like amino acids and the bases that make up RNA and DNA. Interestingly, while on Earth these molecules all have the same “handedness“, the molecules on Bennu are divided about 50/50. Something similar was seen on samples retrieved from another asteroid, so this reinforces the idea that amino acids and nucleotide bases in space do not have a preferred handedness.

I first got into physics for the big deep puzzles, the ones that figure into our collective creation story. Where did the universe come from? Why are its laws the way they are? Over the ten years since I got my PhD, it’s felt like the answers to these questions have gotten further and further away, with new results serving mostly to rule out possible explanations with greater and greater precision.

Biochemistry has its own deep puzzles figuring into our collective creation story, and the biggest one is abiogenesis: how life formed from non-life. What excites me about these observations from Bennu is that it represents real ongoing progress on that puzzle. By glimpsing a soup of ambidextrous molecules, Bennu tells us something about how our own molecules’ handedness could have developed, and rules out ways that it couldn’t have. In physics, if we could see an era of the universe when there were equal amounts of matter and antimatter, we’d be ecstatic: it would confirm that the imbalance between matter and antimatter is a real mystery, and show us where we need to look for the answer. I love that researchers on the origins of life have reason right now to be similarly excited.