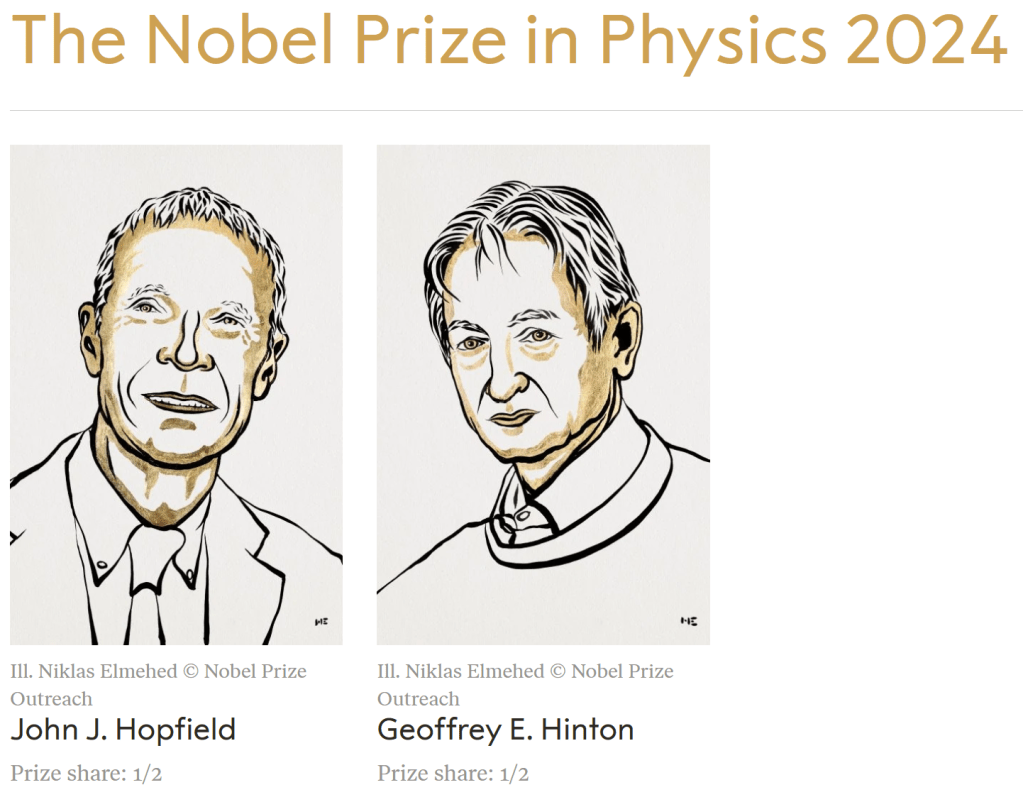

The 2024 Physics Nobel Prize was announced this week, awarded to John Hopfield and Geoffrey Hinton for using physics to propose foundational ideas in the artificial neural networks used for machine learning.

If the picture above looks off-center, it’s because this is the first time since 2015 that the Physics Nobel has been given to two, rather than three, people. Since several past prizes bundled together disparate ideas in order to make a full group of three, it’s noteworthy that this year the committee decided that each of these people deserved 1/2 the prize amount, without trying to find one more person to water it down further.

Hopfield was trained as a physicist, working in the broad area known as “condensed matter physics”. Condensed matter physicists use physics to describe materials, from semiconductors to crystals to glass. Over the years, Hopfield started using this training less for the traditional subject matter of the field and more to study the properties of living systems. He moved from a position in the physics department of Princeton to chemistry and biology at Caltech. While at Caltech he started studying neuroscience and proposed what are now known as Hopfield networks as a model for how neurons store memory. Hopfield networks have very similar properties to a more traditional condensed matter system called a “spin glass”, and from what he knew about those systems Hopfield could make predictions for how his networks would behave. Those networks would go on to be a major inspiration for the artificial neural networks used for machine learning today.

Hinton was not trained as a physicist, and in fact has said that he didn’t pursue physics in school because the math was too hard! Instead, he got a bachelor’s degree in psychology, and a PhD in the at the time nascent field of artificial intelligence. In the 1980’s, shortly after Hopfield published his network, Hinton proposed a network inspired by a closely related area of physics, one that describes temperature in terms of the statistics of moving particles. His network, called a Boltzmann machine, would be modified and made more efficient over the years, eventually becoming a key part of how artificial neural networks are “trained”.

These people obviously did something impressive. Was it physics?

In 2014, the Nobel prize in physics was awarded to the people who developed blue LEDs. Some of these people were trained as physicists, some weren’t: Wikipedia describes them as engineers. At the time, I argued that this was fine, because these people were doing “something physicists are good at”, studying the properties of a physical system. Ultimately, the thing that ties together different areas of physics is training: physicists are the people who study under other physicists, and go on to collaborate with other physicists. That can evolve in unexpected directions, from more mathematical research to touching on biology and social science…but as long as the work benefits from being linked to physics departments and physics degrees, it makes sense to say it “counts as physics”.

By that logic, we can probably call Hopfield’s work physics. Hinton is more uncertain: his work was inspired by a physical system, but so are other ideas in computer science, like simulated annealing. Other ideas, like genetic algorithms, are inspired by biological systems: does that mean they count as biology?

Then there’s the question of the Nobel itself. If you want to get a Nobel in physics, it usually isn’t enough to transform the field. Your idea has to actually be tested against nature. Theoretical physics is its own discipline, with several ideas that have had an enormous influence on how people investigate new theories, ideas which have never gotten Nobels because the ideas were not intended, by themselves, to describe the real world. Hopfield networks and Boltzmann machines, similarly, do not exist as physical systems in the real world. They exist as computer simulations, and it is those computer simulations that are useful. But one can simulate many ideas in physics, and that doesn’t tend to be enough by itself to get a Nobel.

Ultimately, though, I don’t think this way of thinking about things is helpful. The Nobel isn’t capable of being “fair”, there’s no objective standard for Nobel-worthiness, and not much reason for there to be. The Nobel doesn’t determine which new research gets funded, nor does it incentivize anyone (except maybe Brian Keating). Instead, I think the best way of thinking about the Nobel these days is a bit like Disney.

When Disney was young, its movies had to stand or fall on their own merits. Now, with so many iconic movies in its history, Disney movies are received in the context of that history. Movies like Frozen or Moana aren’t just trying to be a good movie by themselves, they’re trying to be a Disney movie, with all that entails.

Similarly, when the Nobel was young, it was just another award, trying to reward things that Alfred Nobel might have thought deserved rewarding. Now, though, each Nobel prize is expected to be “Nobel-like”, an analogy between each laureate and the laureates of the past. When new people are given Nobels the committee is on some level consciously telling a story, saying that these people fit into the prize’s history.

This year, the Nobel committee clearly wanted to say something about AI. There is no Nobel prize for computer science, or even a Nobel prize for mathematics. (Hinton already has the Turing award, the most prestigious award in computer science.) So to say something about AI, the Nobel committee gave rewards in other fields. In addition to physics, this year’s chemistry award went in part to the people behind AlphaFold2, a machine learning tool to predict what shapes proteins fold into. For both prizes, the committee had a reasonable justification. AlphaFold2 genuinely is an amazing advance in the chemistry of proteins, a research tool like nothing that came before. And the work of Hopfield and Hinton did lead ideas in physics to have an enormous impact on the world, an impact that is worth recognizing. Ultimately, though, whether or not these people should have gotten the Nobel doesn’t depend on that justification. It’s an aesthetic decision, one that (unlike Disney’s baffling decision to make live-action remakes of their most famous movies) doesn’t even need to impress customers. It’s a question of whether the action is “Nobel-ish” enough, according to the tastes of the Nobel committee. The Nobel is essentially expensive fanfiction of itself.

And honestly? That’s fine. I don’t think there’s anything else they could be doing at this point.