Could the LHC have killed us all?

No, no it could not.

But…

I’ve had this conversation a few times over the years. Usually, the people I’m talking to are worried about black holes. They’ve heard that the Large Hadron Collider speeds up particles to amazingly high energies before colliding them together. They worry that these colliding particles could form a black hole, which would fall into the center of the Earth and busily gobble up the whole planet.

This pretty clearly hasn’t happened. But also, physicists were pretty confident that it couldn’t happen. That isn’t to say they thought it was impossible to make a black hole with the LHC. Some physicists actually hoped to make a black hole: it would have been evidence for extra dimensions, curled-up dimensions much larger than the tiny ones required by string theory. They figured out the kind of evidence they’d see if the LHC did indeed create a black hole, and we haven’t seen that evidence. But even before running the machine, they were confident that such a black hole wouldn’t gobble up the planet. Why?

The best argument is also the most unsatisfying. The LHC speeds up particles to high energies, but not unprecedentedly high energies. High-energy particles called cosmic rays enter the atmosphere every day, some of which are at energies comparable to the LHC. The LHC just puts the high-energy particles in front of a bunch of sophisticated equipment so we can measure everything about them. If the LHC could destroy the world, cosmic rays would have already done so.

That’s a very solid argument, but it doesn’t really explain why. Also, it may not be true for future colliders: we could build a collider with enough energy that cosmic rays don’t commonly meet it. So I should give another argument.

The next argument is Hawking radiation. In Stephen Hawking’s most famous accomplishment, he argued that because of quantum mechanics black holes are not truly black. Instead, they give off a constant radiation of every type of particle mixed together, shrinking as it does so. The radiation is faintest for large black holes, but gets more and more intense the smaller the black hole is, until the smallest black holes explode into a shower of particles and disappear. This argument means that a black hole small enough that the LHC could produce it would radiate away to nothing in almost an instant: not long enough to leave the machine, let alone fall to the center of the Earth.

This is a good argument, but maybe you aren’t as sure as I am about Hawking radiation. As it turns out, we’ve never measured Hawking radiation, it’s just a theoretical expectation. Remember that the radiation gets fainter the larger the black hole is: for a black hole in space with the mass of a star, the radiation is so tiny it would be almost impossible to detect even right next to the black hole. From here, in our telescopes, we have no chance of seeing it.

So suppose tiny black holes didn’t radiate, and suppose the LHC could indeed produce them. Wouldn’t that have been dangerous?

Here, we can do a calculation. I want you to appreciate how tiny these black holes would be.

From science fiction and cartoons, you might think of a black hole as a kind of vacuum cleaner, sucking up everything nearby. That’s not how black holes work, though. The “sucking” black holes do is due to gravity, no stronger than the gravity of any other object with the same mass at the same distance. The only difference comes when you get close to the event horizon, an invisible sphere close-in around the black hole. Pass that line, and the gravity is strong enough that you will never escape.

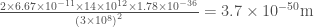

We know how to calculate the position of the event horizon of a black hole. It’s the Schwarzchild radius, and we can write it in terms of Newton’s constant G, the mass of the black hole M, and the speed of light c, as follows:

The Large Hadron Collider’s two beams each have an energy around seven tera-electron-volts, or TeV, so there are 14 TeV of energy in total in each collision. Imagine all of that energy being converted into mass, and that mass forming a black hole. That isn’t how it would actually happen: some of the energy would create other particles, and some would give the black hole a “kick”, some momentum in one direction or another. But we’re going to imagine a “worst-case” scenario, so let’s assume all the energy goes to form the black hole. Electron-volts are a weird physicist unit, but if we divide them by the speed of light squared (as we should if we’re using  to create a mass), then Wikipedia tells us that each electron-volt will give us

to create a mass), then Wikipedia tells us that each electron-volt will give us  kilograms. “Tera” is the SI prefix for

kilograms. “Tera” is the SI prefix for  . Thus our tiny black hole starts with a mass of

. Thus our tiny black hole starts with a mass of

Plugging in Newton’s constant ( meters cubed per kilogram per second squared), and the speed of light (

meters cubed per kilogram per second squared), and the speed of light ( meters per second), and we get a radius of,

meters per second), and we get a radius of,

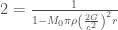

That, by the way, is amazingly tiny. The size of an atom is about  meters. If every atom was a tiny person, and each of that person’s atoms was itself a person, and so on for five levels down, then the atoms of the smallest person would be the same size as this event horizon.

meters. If every atom was a tiny person, and each of that person’s atoms was itself a person, and so on for five levels down, then the atoms of the smallest person would be the same size as this event horizon.

Now, we let this little tiny black hole fall. Let’s imagine it falls directly towards the center of the Earth. The only force affecting it would be gravity (if it had an electrical charge, it would quickly attract a few electrons and become neutral). That means you can think of it as if it were falling through a tiny hole, with no friction, gobbling up anything unfortunate enough to fall within its event horizon.

For our first estimate, we’ll treat the black hole as if it stays the same size through its journey. Imagine the black hole travels through the entire earth, absorbing a cylinder of matter. Using the Earth’s average density of 5515 kilograms per cubic meter, and the Earth’s maximum radius of 6378 kilometers, our cylinder adds a mass of,

That’s absurdly tiny. That’s much, much, much tinier than the mass we started out with. Absorbing an entire cylinder through the Earth makes barely any difference.

You might object, though, that the black hole is gaining mass as it goes. So really we ought to use a differential equation. If the black hole travels a distance r, absorbing mass as it goes at average Earth density  , then we find,

, then we find,

Solving this, we get

Where  is the mass we start out with.

is the mass we start out with.

Plug in the distance through the Earth for r, and we find…still about  ! It didn’t change very much, which makes sense, it’s a very very small difference!

! It didn’t change very much, which makes sense, it’s a very very small difference!

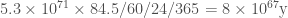

But you might still object. A black hole falling through the Earth wouldn’t just go straight through. It would pass through, then fall back in. In fact, it would oscillate, from one side to the other, like a pendulum. This is actually a common problem to give physics students: drop an object through a hole in the Earth, neglect air resistance, and what does it do? It turns out that the time the object takes to travel through the Earth is independent of its mass, and equal to roughly 84.5 minutes.

So let’s ask a question: how long would it take for a black hole, oscillating like this, to double its mass?

We want to solve,

so we need the black hole to travel a total distance of

That’s a huge distance! The Earth’s radius, remember, is 6378 kilometers. So traveling that far would take

Ten to the sixty-seven years. Our universe is only about ten to the ten years old. In another five times ten to the nine years, the Sun will enter its red giant phase, and swallow the Earth. There simply isn’t enough time for this tiny tiny black hole to gobble up the world, before everything is already gobbled up by something else. Even in the most pessimistic way to walk through the calculation, it’s just not dangerous.

I hope that, if you were worried about black holes at the LHC, you’re not worried any more. But more than that, I hope you’ve learned three lessons. First, that even the highest-energy particle physics involves tiny energies compared to day-to-day experience. Second, that gravitational effects are tiny in the context of particle physics. And third, that with Wikipedia access, you too can answer questions like this. If you’re worried, you can make an estimate, and check!