George Gamow was one of the “quantum kids” who got their start at the Niels Bohr Institute in the 30’s. He’s probably best known for the Alpher, Bethe, Gamow paper, which managed to combine one of the best sources of evidence we have for the Big Bang with a gratuitous Greek alphabet pun. He was the group jester in a lot of ways: the historians here have archives full of his cartoons and in-jokes.

Naturally, he also did science popularization.

I recently read two of Gamow’s science popularization books, “Mr Tompkins” and “Thirty Years That Shook Physics”. Reading them was a trip back in time, to when people thought about physics in surprisingly different ways.

“Mr. Tompkins” started as a series of articles in Discovery, a popular science magazine. They were published as a book in 1940, with a sequel in 1945 and an update in 1965. Apparently they were quite popular among a certain generation: the edition I’m reading has a foreword by Roger Penrose.

(As an aside: Gamow mentions that the editor of Discovery was C. P. Snow…that C. P. Snow?)

Mr Tompkins himself is a bank clerk who decides on a whim to go to a lecture on relativity. Unable to keep up, he falls asleep, and dreams of a world in which the speed of light is much slower than it is in our world. Bicyclists visibly redshift, and travelers lead much longer lives than those who stay at home. As the book goes on he meets the same professor again and again (eventually marrying his daughter) and sits through frequent lectures on physics, inevitably falling asleep and experiencing it first-hand: jungles where Planck’s constant is so large that tigers appear as probability clouds, micro-universes that expand and collapse in minutes, and electron societies kept strictly monogamous by “Father Paulini”.

The structure definitely feels dated, and not just because these days people don’t often go to physics lectures for fun. Gamow actually includes the full text of the lectures that send Mr Tompkins to sleep, and while they’re not quite boring enough to send the reader to sleep they are written on a higher level than the rest of the text, with more technical terms assumed. In the later additions to the book the “lecture” aspect grows: the last two chapters involve a dream of Dirac explaining antiparticles to a dolphin in basically the same way he would explain them to a human, and a discussion of mesons in a Japanese restaurant where the only fantastical element is a trio of geishas acting out pion exchange.

Some aspects of the physics will also feel strange to a modern audience. Gamow presents quantum mechanics in a way that I don’t think I’ve seen in a modern text: while modern treatments start with uncertainty and think of quantization as a consequence, Gamow starts with the idea that there is a minimum unit of action, and derives uncertainty from that. Some of the rest is simply limited by timing: quarks weren’t fully understood even by the 1965 printing, in 1945 they weren’t even a gleam in a theorist’s eye. Thus Tompkins’ professor says that protons and neutrons are really two states of the same particle and goes on to claim that “in my opinion, it is quite safe to bet your last dollar that the elementary particles of modern physics [electrons, protons/neutrons, and neutrinos] will live up to their name.” Neutrinos also have an amusing status: they hadn’t been detected when the earlier chapters were written, and they come across rather like some people write about dark matter today, as a silly theorist hypothesis that is all-too-conveniently impossible to observe.

“Thirty Years That Shook Physics”, published in 1966, is a more usual sort of popular science book, describing the history of the quantum revolution. While mostly focused on the scientific concepts, Gamow does spend some time on anecdotes about the people involved. If you’ve read much about the time period, you’ll probably recognize many of the anecdotes (for example, the Pauli Principle that a theorist can break experimental equipment just by walking in to the room, or Dirac’s “discovery” of purling), even the ones specific to Gamow have by now been spread far and wide.

Like Mr Tompkins, the level in this book is not particularly uniform. Gamow will spend a paragraph carefully defining an average, and then drop the word “electroscope” as if everyone should know what it is. The historical perspective taught me a few things I perhaps should have already known, but found surprising anyway. (The plum-pudding model was an actual mathematical model, and people calculated its consequences! Muons were originally thought to be mesons!)

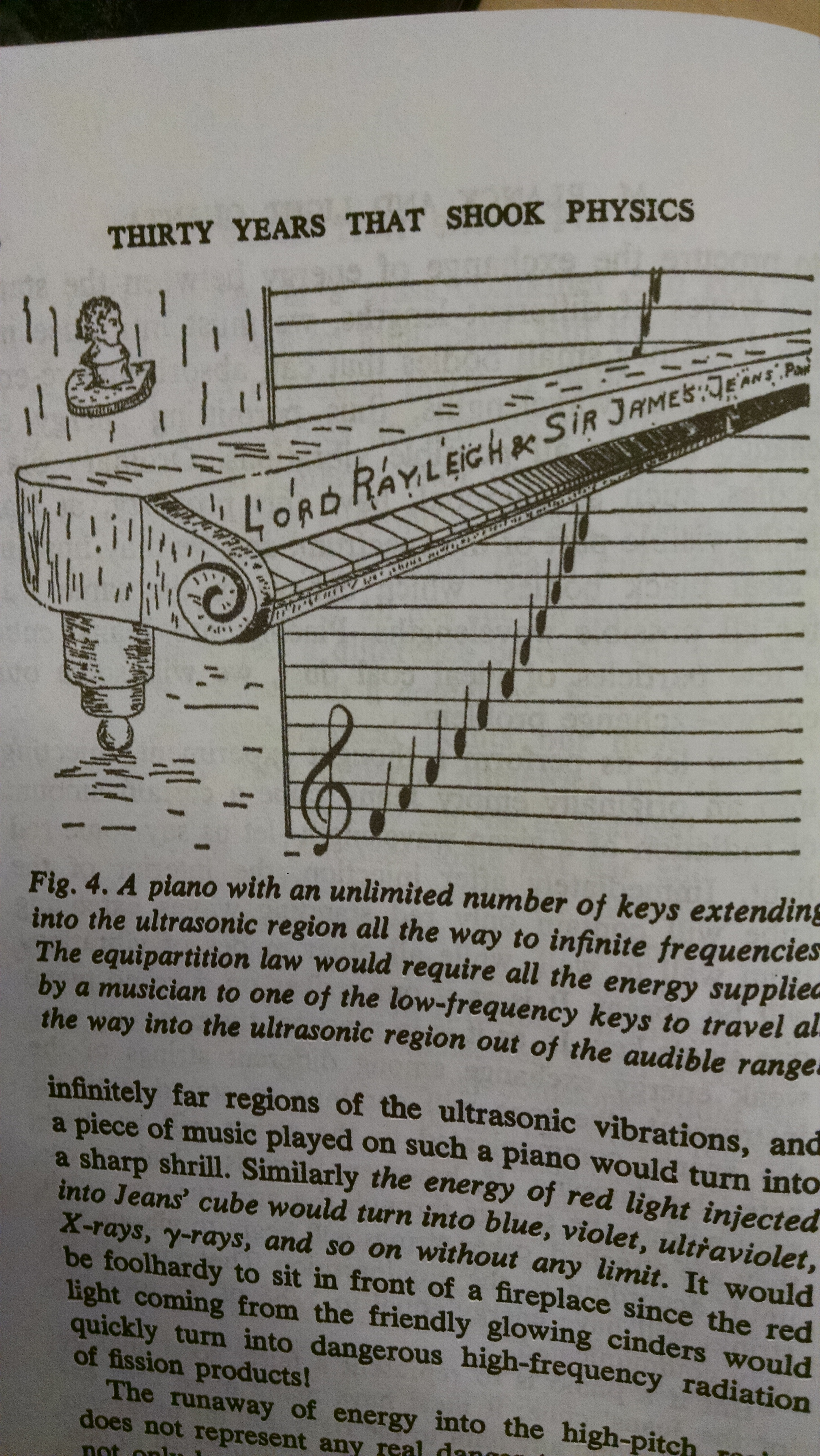

Both books are filled with Gamow’s whimsical illustrations, something he was very much known for. Apparently he liked to imitate other art styles as well, which is visible in the portraits of physicists at the front of each chapter.

1966 was late enough that this book doesn’t have the complacency of the earlier chapters in Mr Tompkins: Gamow knew that there were more particles than just electrons, nucleons, and neutrinos. It was still early enough, though, that the new particles were not fully understood. It’s interesting seeing how Gamow reacts to this: his expectation was that physics was on the cusp of another massive change, a new theory built on new fundamental principles. He speculates that there might be a minimum length scale (although oddly enough he didn’t expect it to be related to gravity).

It’s only natural that someone who lived through the dawn of quantum mechanics should expect a similar revolution to follow. Instead, the revolution of the late 60’s and early 70’s was in our understanding: not new laws of nature so much as new comprehension of just how much quantum field theory can actually do. I wonder if the generation who lived through that later revolution left it with the reverse expectation: that the next crisis should be solved in a similar way, that the world is quantum field theory (or close cousins, like string theory) all the way down and our goal should be to understand the capabilities of these theories as well as possible.

The final section of the book is well worth waiting for. In 1932, Gamow directed Bohr’s students in staging a play, the “Blegdamsvej Faust”. A parody of Faust, it features Bohr as god, Pauli as Mephistopheles, and Ehrenfest as the “erring Faust” (Gamow’s pun, not mine) that he tempts to sin with the promise of the neutrino, Gretchen. The piece, translated to English by Gamow’s wife Barbara, is filled with in-jokes on topics as obscure as Bohr’s habitual mistakes when speaking German. It’s gloriously weird and well worth a read. If you’ve ever seen someone do a revival performance, let me know!