I’ve got unification on the brain.

Recently, a commenter asked me what physicists mean when they say two forces unify. While typing up a response, I came across this passage, in a science fiction short story by Ted Chiang.

Physics admits of a lovely unification, not just at the level of fundamental forces, but when considering its extent and implications. Classifications like ‘optics’ or ‘thermodynamics’ are just straitjackets, preventing physicists from seeing countless intersections.

This passage sounds nice enough, but I feel like there’s a misunderstanding behind it. When physicists seek after unification, we’re talking about something quite specific. It’s not merely a matter of two topics intersecting, or describing them with the same math. We already plumb intersections between fields, including optics and thermodynamics. When we hope to find a unified theory, we do so because it does something. A real unified theory doesn’t just aid our calculations, it gives us new ways to alter the world.

To show you what I mean, let me start with something physicists already know: electroweak unification.

There’s a nice series of posts on the old Quantum Diaries blog that explains electroweak unification in detail. I’ll be a bit vaguer here.

You might have heard of four fundamental forces: gravity, electromagnetism, the strong nuclear force, and the weak nuclear force. You might have also heard that two of these forces are unified: the electromagnetic force and the weak nuclear force form something called the electroweak force.

What does it mean that these forces are unified? How does it work?

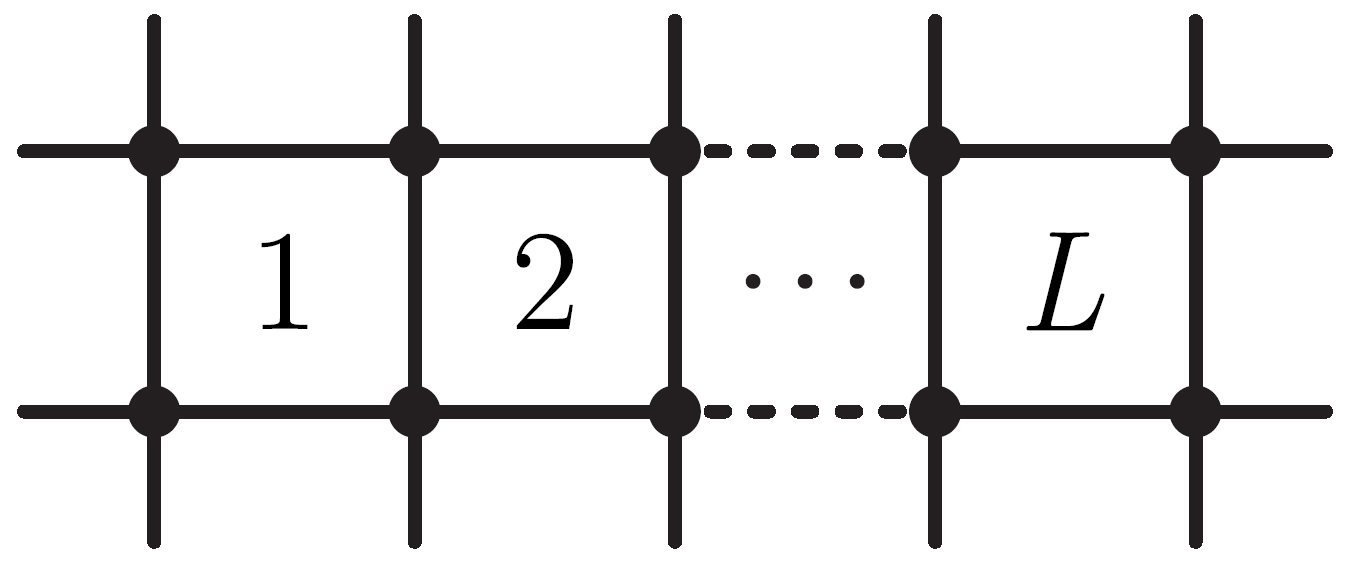

Zoom in far enough, and you don’t see the electromagnetic force and the weak force anymore. Instead you see two different forces, I’ll call them “W” and “B”. You’ll also see the Higgs field. And crucially, you’ll see the “W” and “B” forces interact with the Higgs.

The Higgs field is special because it has what’s called a “vacuum” value. Even in otherwise empty space, there’s some amount of “Higgsness” in the background, like the color of a piece of construction paper. This background Higgs-ness is in some sense an accident, just one stable way the universe happens to sit. In particular, it picks out an arbitrary kind of direction: parts of the “W” and “B” forces happen to interact with it, and parts don’t.

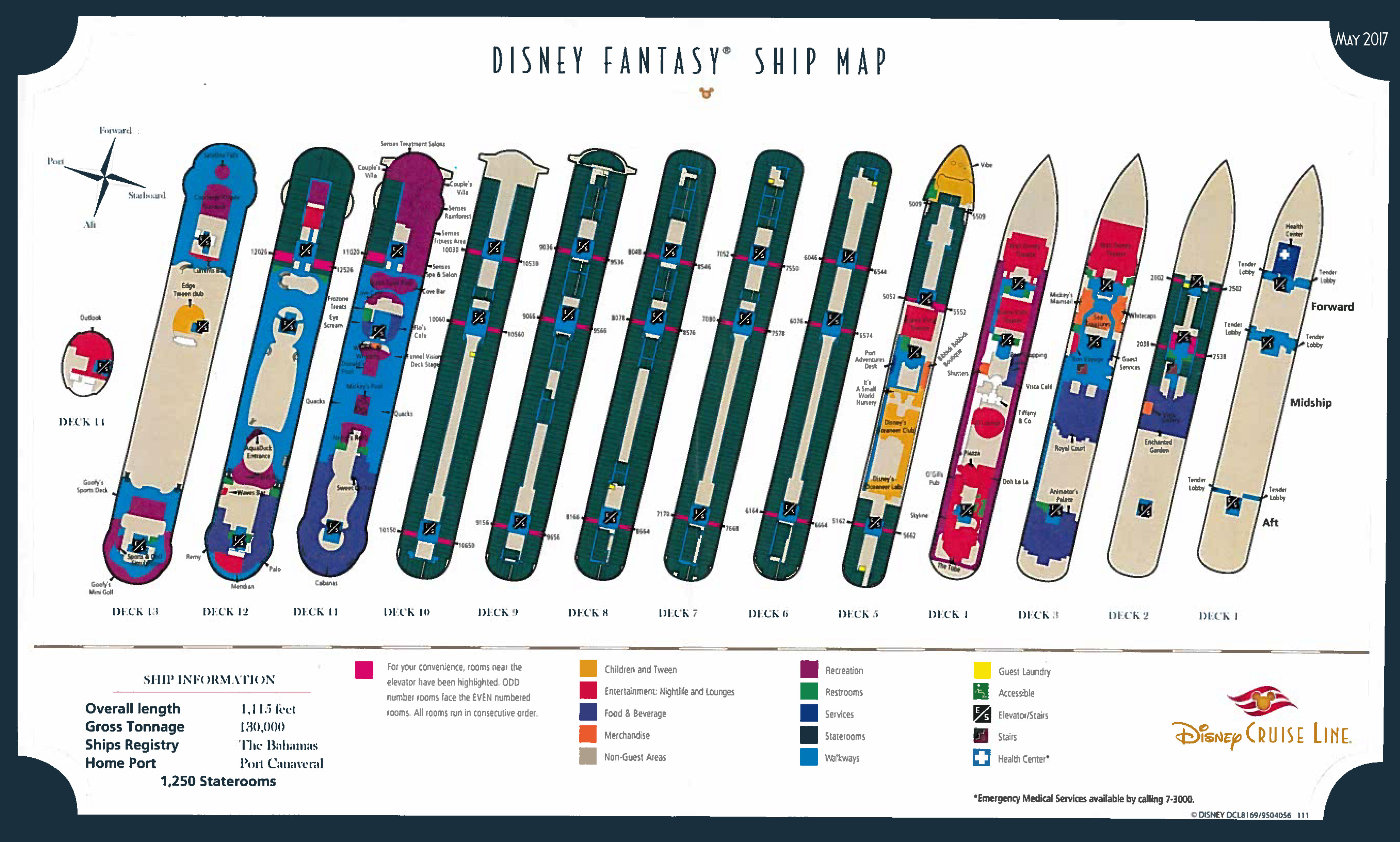

Now let’s zoom back out. We could, if we wanted, keep our eyes on the “W” and “B” forces. But that gets increasingly silly. As we zoom out we won’t be able to see the Higgs field anymore. Instead, we’ll just see different parts of the “W” and “B” behaving in drastically different ways, depending on whether or not they interact with the Higgs. It will make more sense to talk about mixes of the “W” and “B” fields, to distinguish the parts that are “lined up” with the background Higgs and the parts that aren’t. It’s like using “aft” and “starboard” on a boat. You could use “north” and “south”, but that would get confusing pretty fast.

What are those “mixes” of the “W” and “B” forces? Why, they’re the weak nuclear force and the electromagnetic force!

This, broadly speaking, is the kind of unification physicists look for. It doesn’t have to be a “mix” of two different forces: most of the models physicists imagine start with a single force. But the basic ideas are the same: that if you “zoom in” enough you see a simpler model, but that model is interacting with something that “by accident” picks a particular direction, so that as we zoom out different parts of the model behave in different ways. In that way, you could get from a single force to all the different forces we observe.

That “by accident” is important here, because that accident can be changed. That’s why I said earlier that real unification lets us alter the world.

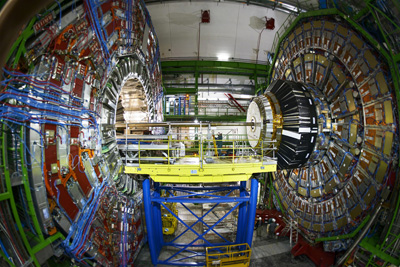

To be clear, we can’t change the background Higgs field with current technology. The biggest collider we have can just make a tiny, temporary fluctuation (that’s what the Higgs boson is). But one implication of electroweak unification is that, with enough technology, we could. Because those two forces are unified, and because that unification is physical, with a physical cause, it’s possible to alter that cause, to change the mix and change the balance. This is why this kind of unification is such a big deal, why it’s not the sort of thing you can just chalk up to “interpretation” and ignore: when two forces are unified in this way, it lets us do new things.

Mathematical unification is valuable. It’s great when we can look at different things and describe them in the same language, or use ideas from one to understand the other. But it’s not the same thing as physical unification. When two forces really unify, it’s an undeniable physical fact about the world. When two forces unify, it does something.