There are a lot of people who think theoretical physics has gone off-track, though very few of them agree on exactly how. Some think that string theory as a whole is a waste of time, others that the field just needs to pay more attention to their preferred idea. Some think we aren’t paying enough attention to the big questions, or that we’re too focused on “safe” ideas like supersymmetry, even when they aren’t working out. Some think the field needs less focus on mathematics, while others think it needs even more.

Usually, people act on these opinions by writing strongly worded articles and blog posts. Sometimes, they have more power, and act with money, creating grants and prizes that only go to their preferred areas of research.

Let’s put the question of whether the field actually needs to change aside for the moment. Even if it does, I’m skeptical that this sort of thing will have any real effect. While grants and blogs may be very good at swaying experimentalists, theorists are likely to be harder to shift, due to what I’m going to call the Theorist Exclusion Principle.

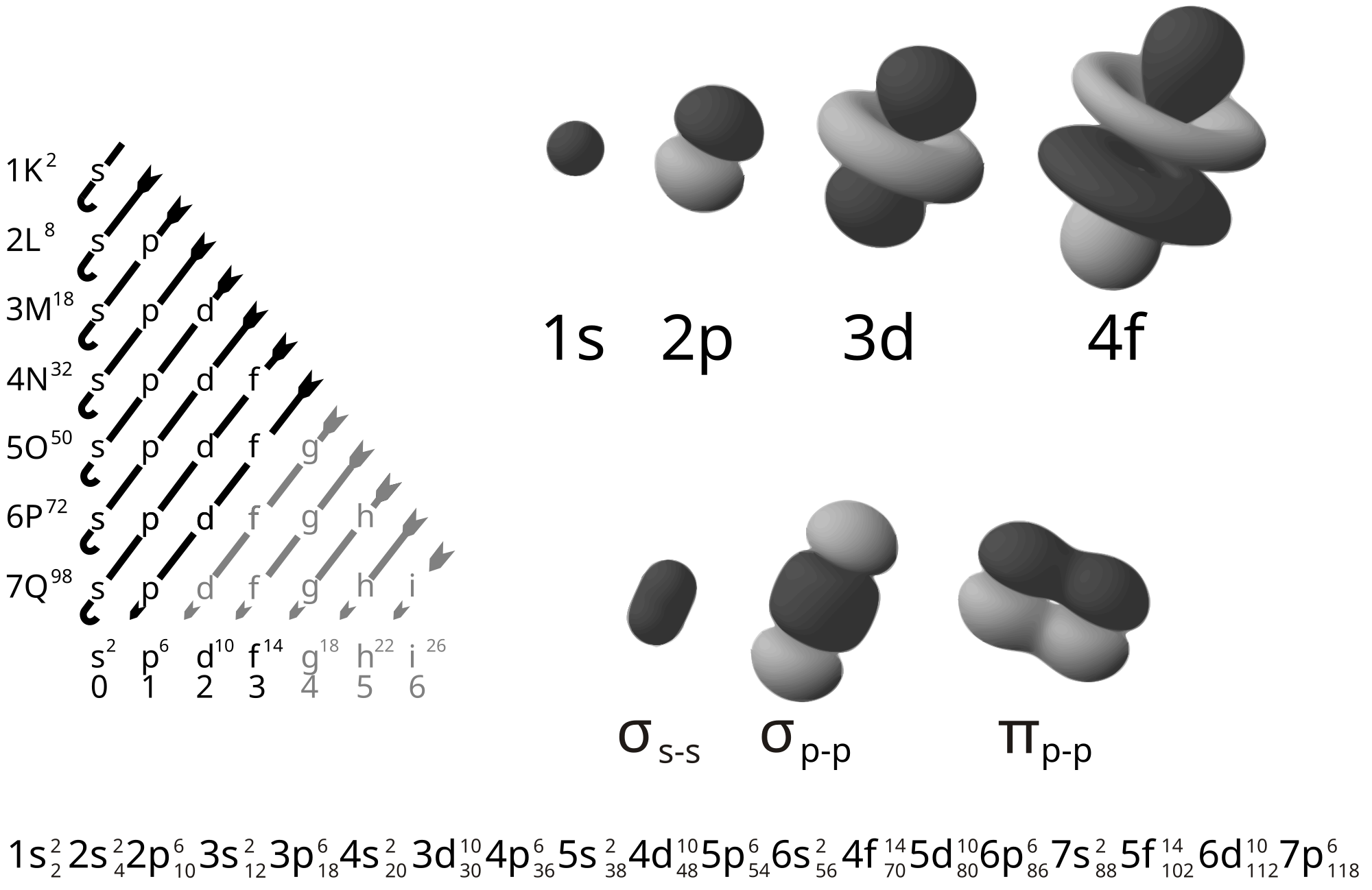

The Pauli Exclusion Principle is a rule from quantum mechanics that states that two fermions (particles with half-integer spin) can’t occupy the same state. Fermions include electrons, quarks, protons…essentially, all the particles that make up matter. Many people learn about the Pauli Exclusion Principle first in a chemistry class, where it explains why electrons fall into different energy levels in atoms: once one energy level “fills up”, no more electrons can occupy the same state, and any additional electrons are “excluded” and must occupy a different energy level.

In contrast, bosons (like photons, or the Higgs) can all occupy the same state. It’s what allows for things like lasers, and it’s why all the matter we’re used to is made out of fermions: because fermions can’t occupy the same state as each other, as you add more fermions the structures they form have to become more and more complicated.

Experimentalists are a little like bosons. While you can’t stuff two experimentalists into the same quantum state, you can get them working on very similar projects. They can form large collaborations, with each additional researcher making the experiment that much easier. They can replicate eachother’s work, making sure it was accurate. They can take some physical phenomenon and subject it to a battery of tests, so that someone is bound to learn something.

Theorists, on the other hand, are much more like fermions. In theory, there’s very little reason to work on something that someone else is already doing. Replication doesn’t mean very much: the purest theory involves mathematical proofs, where replication is essentially pointless. Theorists do form collaborations, but they don’t have the same need for armies of technicians and grad students that experimentalists do. With no physical objects to work on, there’s a limit to how much can be done pursuing one particular problem, and if there really are a lot of options they can be pursued by one person with a cluster.

Like fermions, then, theorists expand to fill the projects available. If an idea is viable, someone will probably work on it, and once they do, there isn’t much reason for someone else to do the same thing.

This makes theory a lot harder to influence than experiment. You can write the most beautiful thinkpiece possible to persuade theorists to study the deep questions of the universe, but if there aren’t any real calculations available nothing will change. Contrary to public perception, theoretical physicists aren’t paid to just sit around thinking all day: we calculate, compute, and publish, and if a topic doesn’t lend itself to that then we won’t get much mileage out of it. And no matter what you try to preferentially fund with grants, mostly you’ll just get people re-branding what they’re already doing, shifting a few superficial details to qualify.

Theorists won’t occupy the same states, so if you want to influence theorists you need to make sure there are open states where you’re trying to get them to go. Historically, theorists have shifted when new states have opened up: new data from experiment that needed a novel explanation, new mathematical concepts that opened up new types of calculations. You want there to be fewer string theorists, or more focus on the deep questions? Give us something concrete to do, and I guarantee you’ll get theorists flooding in.