I’ve complained before about how mathematicians name things. Mathematicans seem to have a knack for taking an ordinary bland word that’s almost indistinguishable from the other ordinary, bland words they’ve used before and assigning it an incredibly specific mathematical concept. Varieties and forms, motives and schemes, in each case you end up wishing they picked a word that was just a little more descriptive.

Sometimes, though, a word may seem completely out of place when it actually has a fairly reasonable explanation. Such is the case for the word “period“.

Suppose you want to classify numbers. You have the integers, and the rational numbers. A bigger class of numbers are “algebraic”, in that you can get them “from algebra”: more specifically, as solutions of polynomial equations with rational coefficients. Numbers that aren’t algebraic are “transcendental”, a popular example being .

Periods lie in between: a set that contains algebraic numbers, but also many of the transcendental numbers. They’re numbers you can get, not from algebra, but from calculus: they’re integrals over rational functions. These numbers were popularized by Kontsevich and Zagier, and they’ve led to a lot of fruitful inquiry in both math and physics.

But why the heck are they called periods?

Think about .

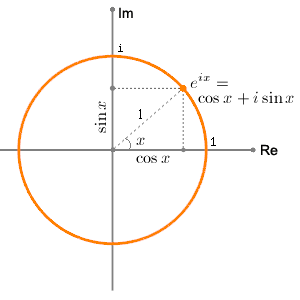

Or if you prefer, think about a circle

is a periodic function, with period

. Take

from

to

and the function repeats, you’ve traveled in a circle.

Thought of another way, is the volume of the circle. It’s the integral, around the circle, of

. And that integral nicely matches Kontsevich and Zagier’s definition of a period.

The idea of a period, then, comes from generalizing this. What happens when you only go partway around the circle, to some point in the complex plane? Then you need to go to a point

. So a logarithm can also be thought of as measuring the period of

. And indeed, since a logarithm can be expressed as

, they count as periods in the Kontsevich-Zagier sense.

Starting there, you can loosely think about the polylogarithm functions I like to work with as collections of logs, measuring periods of interlocking circles.

And if you need to go beyond polylogarithms, when you can’t just go circle by circle?

Then you need to think about functions with two periods, like Weierstrass’s elliptic function. Just as you can think about as a circle, you can think of Weierstrass’s function in terms of a torus.

The torus has two periods, corresponding to the two circles you can draw around it. The periods of Weierstrass’s function are transcendental numbers, and they fit Kontsevich and Zagier’s definition of periods. And if you take the inverse of Weierstrass’s function, you get an elliptic integral, just like taking the inverse of gives a logarithm.

So mathematicians, I apologize. Periods, at least, make sense.

I’m still mad about “varieties” though.