How can colliding two protons give rise to more massive particles? Why do vibrations of a string have mass? And how does the Higgs work anyway?

There is one central misunderstanding that makes each of these topics confusing. It’s something I’ve brought up before, but it really deserves its own post. It’s people not realizing that mass is just energy you haven’t met yet.

It’s quite intuitive to think of mass as some sort of “stuff” that things can be made out of. In our everyday experience, that’s how it works: combine this mass of flour and this mass of sugar, and get this mass of cake. Historically, it was the dominant view in physics for quite some time. However, once you get to particle physics it starts to break down.

It’s probably most obvious for protons. A proton has a mass of 938 MeV/c², or 1.6×10⁻²⁷ kg in less physicist-specific units. Protons are each made of three quarks, two up quarks and a down quark. Naively, you’d think that the quarks would have to be around 300 MeV/c². They’re not, though: up and down quarks both have masses less than 10 MeV/c². Those three quarks account for less than a fiftieth of a proton’s mass.

The “extra” mass is because a proton is not just three quarks. It’s three quarks interacting. The forces between those quarks, the strong nuclear force that binds them together, involves a heck of a lot of energy. And from a distance, that energy ends up looking like mass.

This isn’t unique to protons. In some sense, it’s just what mass is.

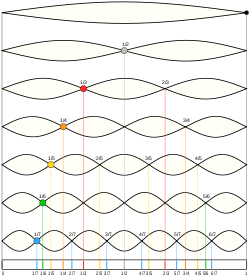

The quarks themselves get their mass from the Higgs field. Far enough away, this looks like the quarks having a mass. However, zoom in and it’s energy again, the energy of interaction between quarks and the Higgs. In string theory, mass comes from the energy of vibrating strings. And so on. Every time we run into something that looks like a fundamental mass, it ends up being just another energy of interaction.

If mass is just energy, what about gravity?

When you’re taught about gravity, the story is all about mass. Mass attracts mass. Mass bends space-time. What gets left out, until you actually learn the details of General Relativity, is that energy gravitates too.

Normally you don’t notice this, because mass contributes so much more to energy than anything else. That’s really what E=mc² is really about: it’s a unit conversion formula. It tells you that if you want to know how much energy a given mass “really is”, you multiply it by the speed of light squared. And that’s a large enough number that most of the time, when you notice energy gravitating, it’s because that energy looks like a big chunk of mass. (It’s also why physicists like silly units like MeV/c² for mass: we can just multiply by c² and get an energy!)

It’s really tempting to think about mass as a substance, of mass as always conserved, of mass as fundamental. But in physics we often have to toss aside our everyday intuitions, and this is no exception. Mass really is just energy. It’s just energy that we’ve “zoomed out” enough not to notice.