A few days ago, my sister asked me what I do at work. What do I actually do in order to do my job? What sort of tasks does it involve?

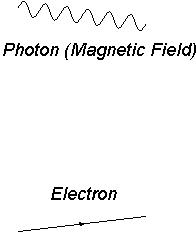

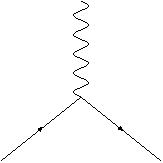

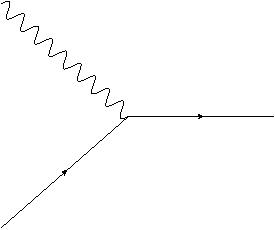

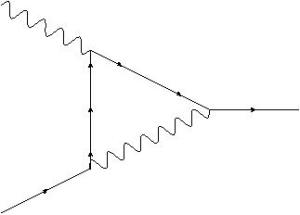

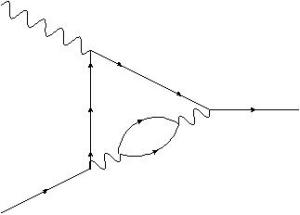

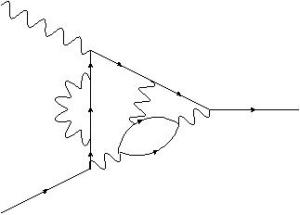

I answered by showing her this:

Needless to say, that wasn’t very helpful, so I thought a bit and now I have a better answer.

Doing theoretical physics is basically like doing homework. In particular, it’s like doing difficult, interesting homework.

Think of the toughest homework assignment you’ve ever had to do. A homework assignment so tough, you and all your friends in the class worked together to finish it, and none of you were sure you were going to get it right.

Chances are, you handled the situation in one of two ways, depending on whether this was a group project, or an individual one.

Group Project:

This is what you do when you’re supposed to be in a group. Maybe you’re putting together a presentation, or building a rocket. Whatever you’re doing, you’ve got a lot of little tasks that need to get done in order to achieve your goals, so you parcel them out: each group member is assigned a specific task, and at the end everyone meets and puts it all together.

This sort of situation is common in theoretical physics as well, and it happens when different people have different skills to contribute. If one theorist is good at programming, while another understands a particular esoteric type of mathematics, then the math person will do the calculations and then give the results to the programming person, who makes a program to implement it.

Individual Project:

On the other hand, if everyone needs to submit their own work, you can’t very well just do part of it (not without cheating, anyway). Still, it’s not as if you’re doing this on your own. You do your own work to solve the problem, but you keep in contact with your classmates, and when you get stuck, you ask one of them for help.

This sort of situation happens in theoretical physics when everyone is relatively on the same page. Everyone works through the problem individually, doing the calculation and making their own programs, and whenever someone gets stuck, they talk to the others. Everyone periodically compares their results, which serves as a cross-check to make sure nobody made a mistake. The only difference from doing homework is that you and your collaborators write your own problems…which means, none of you know if there is a solution!

In both cases (group and individual), theoretical physics is a matter of doing calculations, writing programs, and thinking through thought experiments. Sometimes that means specific tasks as part of one huge project; sometimes it means working side by side on the same calculation. Either way, it all boils down to one thing: I’m someone who does homework for a living.