The best misunderstandings are detective stories. You can notice when someone is confused, but digging up why can take some work. If you manage, though, you learn much more than just how to correct the misunderstanding. You learn something about the words you use, and the assumptions you make when using them.

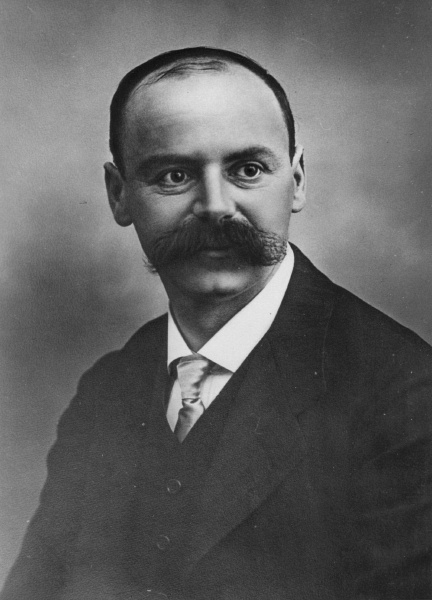

Recently, someone was telling me about a book they’d read on Karl Schwarzschild. Schwarzschild is famous for discovering the equations that describe black holes, based on Einstein’s theory of gravitation. To make the story more dramatic, he did so only shortly before dying from a disease he caught fighting in the first World War. But this person had the impression that Schwarzschild had done even more. According to this person, the book said that Schwarzschild had done something to prove Einstein’s theory, or to complete it.

At first, I thought the book this person had read was wrong. But after some investigation, I figured out what happened.

The book said that Schwarzschild had found the first exact solution to Einstein’s equations. That’s true, and as a physicist I know precisely what it means. But I now realize that the average person does not.

In school, the first equations you solve are algebraic, x+y=z. Some equations, like x^2=4, have solutions. Others, like x^2=-4, seem not to, until you learn about new types of numbers that solve them. Either way, you get used to equations being like a kind of puzzle, a question for which you need to find an answer.

If you’re thinking of equations like that, then it probably sounds like Schwarzschild “solved the puzzle”. If Schwarzschild found the first solution to Einstein’s equation, that means that Einstein did not. That makes it sound like Einstein’s work was incomplete, that he had asked the right question but didn’t yet know the right answer.

Einstein’s equations aren’t algebraic equations, though. They’re differential equations. Instead of equations for a variable, they’re equations for a mathematical function, a formula that, in this case, describes the curvature of space and time.

Scientists in many fields use differential equations, but they use them in different ways. If you’re a chemist or a biologist, it might be that you’re most used to differential equations with simple solutions, like sines, cosines, or exponentials. You learn how to solve these equations, and they feel a bit like the algebraic ones: you have a puzzle, and then you solve the puzzle.

Other fields, though, have tougher differential equations. If you’re a physicist or an engineer, you’ve likely met differential equations that you can’t treat in this way. If you’re dealing with fluid mechanics, or general relativity, or even just Newtonian gravity in an odd situation, you can’t usually solve the problem by writing down known functions like sines and cosines.

That doesn’t mean you can’t solve the problem at all, though!

Even if you can’t write down a solution to a differential equation with sines and cosines, a solution can still exist. (In some cases, we can even prove a solution exists!) It just won’t be written in terms of sines and cosines, or other functions you’ve learned in school. Instead, the solution will involve some strange functions, functions no-one has heard of before.

If you want, you can make up names for those functions. But unless you’re going to classify them in a useful way, there’s not much point. Instead, you work with these functions by approximation. You calculate them in a way that doesn’t give you the full answer, but that does let you estimate how close you are. That’s good enough to give you numbers, which in turn is good enough to compare to experiments. With just an approximate solution, like this, Einstein could check if his equations described the orbit of Mercury.

Once you know you can find these approximate solutions, you have a different perspective on equations. An equation isn’t just a mysterious puzzle. If you can approximate the solution, then you already know how to solve that puzzle. So we wouldn’t think of Einstein’s theory as incomplete because he was only able to find approximate solutions: for a theory as complicated as Einstein’s, that’s perfectly normal. Most of the time, that’s all we need.

But it’s still pretty cool when you don’t have to do this. Sometimes, we can not just approximate, but actually “write down” the solution, either using known functions or well-classified new ones. We call a solution like that an analytic solution, or an exact solution.

That’s what Schwarzschild managed. These kinds of exact solutions often only work in special situations, and Schwarzschild’s is no exception. His Schwarzschild solution works for matter in a special situation, arranged in a perfect sphere. If matter happened to be arranged in that way, then the shape of space and time would be exactly as Schwarzschild described it.

That’s actually pretty cool! Einstein’s equations are complicated enough that no-one was sure that there were any solutions like that, even in very special situations. Einstein expected it would be a long time until they could do anything except approximate solutions.

(If Schwarzschild’s solution only describes matter arranged in a perfect sphere, why do we think it describes real black holes? This took later work, by people like Roger Penrose, who figured out that matter compressed far enough will always find a solution like Schwarzschild’s.)

Schwarzschild intended to describe stars with his solution, or at least a kind of imaginary perfect star. What he found was indeed a good approximation to real stars, but also the possibility that a star shoved into a sufficiently small space would become something weird and new, something we would come to describe as a black hole. That’s a pretty impressive accomplishment, especially for someone on the front lines of World War One. And if you know the difference between an exact solution and an approximate one, you have some idea of what kind of accomplishment that is.

This was a great post! Extremely clear. You do a great job of making your points in a concrete way illustrated by examples.

A lot of papers in GR are done in spherically symmetric mass distributions for practical, mathematical manageability reasons you indicate. Are there any analytic/exact solutions that are not spherically symmetric?

(Forgive me if you’ve already posted on it and I missed that post/those posts.)

Given that your work (and indeed the name of your blog) ties directly into quantum gravity, maybe someday you could comment in a post on the proposition that Einstein’s Field Equations are equivalent to the physics of a massless spin-2 boson that couples in proportion to mass-energy with a coupling constant equivalent with the appropriate dimensional adjustments to Newton’s constant G (or some angle or piece of that).

I’ve heard this stated, but it isn’t clear to me how rigorously it has been proved (maybe it is even just a hypothesis) or with what conditions.

What was the outline of the reasoning behind the proof if it has been proved rigorously (at least subject to some conditions)?

At a minimum this equivalence surely has to be true only in the classical limit, because the way that a quantum field theory works and the way that a classical field theory works, generically, are not identical.

The physics of a massless spin-2 boson ought to be expressed in amplitudes giving rise to probabilities, while Einstein’s Field Equations are deterministic.

Gravitons would seem to localize gravitational energy which the leading textbooks (e.g. MTW “Gravitation”) states can’t be done in classical GR.

Does a massless spin-2 boson theory dispense with the need to consider space-time curvature?

Can it, generically, have singularities?

Are the Lagrangians different?

It would be interesting to see a list of the ways that generically, and qualitatively, there have to be differences between classical GR and the physics massless spin-2 boson with the right properties.

Obviously, quantum gravity is not a solved problem, or you wouldn’t have a job waiting for you in France.

But, one of the things I’ve always liked about Feynman (which you and Matt Strassler are also very good about) is that he didn’t get too hung up speculating about what we don’t know, and instead placing an emphasis on the rather impressive stuff that we do know to a high comfort level even if it isn’t everything that is out there to be known about the subject, since that doesn’t always get talked about as much since it isn’t new and shiny in the latest arXiv preprints and conference papers.

It seems like there is already a lot of widely assumed knowledge about quantum gravity, especially at the qualitative level, that isn’t very controversial, despite the fact that there are real problems like non-renormalizability, at least in some contexts, that we haven’t figured out yet.

LikeLike

There are indeed exact solutions that are not spherically symmetric. The most famous is the Kerr solution, for a rotating black hole (not spherically symmetric because there’s a preferred axis of rotation). Gravitational waves are another example. If you’re interested in others, this Wikipedia article and the links in it is probably a good starting point.

Regarding the statement that the Einstein Field Equations are equivalent to a spin-2 massless boson, the first page in my guide to N=8 supergravity is all about motivating exactly that statement. In general that series has partial answers to a few of your questions, but I’ll try to give you more thorough answers below.

First: if you want to know whether two statements are equivalent, you’re looking for an “if and only if”: each statement should imply the other one.

In one direction: if you start from the Einstein-Hilbert Lagrangian and quantize it in the “normal way” (the same way we do for say Maxwell’s equations), then you get a quantum field theory of the metric, . That metric is a spin-two bosonic field, and Einstein’s field equations tell you it is massless. Because it’s exactly the same process as for Maxwell E&M, you’re explicitly going from a classical to a quantum theory: you use the same Lagrangian, but instead of solving the Euler-Lagrange equations you plug them into a path integral. The theory you get does have divergences, is not renormalizable, and at high energies violates unitarity (gives probabilities greater than one). The latter means that it can’t be a fundamental theory of nature, but could be a low-energy limit of one, so in practice quantum gravity researchers try to find a theory such that this theory is its low-energy limit.

. That metric is a spin-two bosonic field, and Einstein’s field equations tell you it is massless. Because it’s exactly the same process as for Maxwell E&M, you’re explicitly going from a classical to a quantum theory: you use the same Lagrangian, but instead of solving the Euler-Lagrange equations you plug them into a path integral. The theory you get does have divergences, is not renormalizable, and at high energies violates unitarity (gives probabilities greater than one). The latter means that it can’t be a fundamental theory of nature, but could be a low-energy limit of one, so in practice quantum gravity researchers try to find a theory such that this theory is its low-energy limit.

That direction is all 100% well-established, you just follow a straightforward procedure and that’s what pops out.

In the other direction, you could ask: suppose you have a theory of a massless spin-two boson. Is that theory gravity? Does it obey the Einstein Field Equations?

The answer is mostly yes, but it’s a bit subtle. You might notice I didn’t put your statement about how the particle couples there. That’s because Weinberg proved you get that for free: if you have a massless spin-two boson and it couples to anything at all, then you can prove it has to couple to all matter equally, and that there can only be one such field.

You can then go on to ask how this field will behave. Using amplitudes methods, you can write down a unique three-particle interaction for the field, then use it to build up interactions with more particles. You can prove that this procedure gives the same interactions you would get from the quantization procedure I described a few paragraphs up: the scattering amplitudes you compute are precisely those you would get from treating the Einstein-Hilbert Lagrangian as a Lagrangian for a quantum field theory with the metric as the field.

Now, all of these amplitudes calculations are perturbative, approximating the coupling as small. It may be that non-perturbatively things aren’t unique, there might be more than one theory that gives the same perturbative expansion. But up to that, the statements hold.

This also should answer your question about localization of the energy. Gravitons are treated as a small perturbation on top of a (usually) Minkowski metric, and in that situation you can approximately describe a sensible localized energy. But indeed when that approximation breaks down you shouldn’t think of gravitons, or indeed anything else, as localized. (The slogan is “there are no local observables in quantum gravity.)

LikeLike

I’m realizing there are a couple more things I didn’t address above:

Regarding whether you “dispense with the need to consider space-time curvature”, I wouldn’t say it dispenses with it, they’re just two different descriptions of the same thing, in the same way that you can describe something as a quantum electromagnetic field or as a spin-one boson.

Regarding singularities, I was thinking you were asking about divergences, but you were probably asking about space-time singularities, like the center of the Schwarzschild solution, right? The type of naive quantum gravity I describe above can’t answer that question, because at energies that are high compared to the Planck energy (equivalently, lengths small compared to the Planck length), the theory breaks down and gives probabilities greater than one, so it can’t tell you whether those singularities are real or not. A full theory of quantum gravity that solves that problem is expected to not have space-time singularities, and the (supersymmetric) examples of black holes people can investigate with string theory indeed don’t have space-time singularities.

Finally, I wouldn’t say that my job in France has that much to do with the problem of quantum gravity, certainly it didn’t come up much in the job talk! I may do some work related to quantum gravity in future, but in the near-term I’m more interested in figuring out how to reliably make predictions for near-term experiments (including the LHC, but also classical gravitational experiments like LIGO) and to explain some of the mathematical mysteries we’ve been seeing in supersymmetric theories.

LikeLike