I was at a mini-conference this week, called Jumpstarting Elliptic Bootstrap Methods for Scattering Amplitudes.

I’ve done a lot of work with what we like to call “bootstrap” methods. Instead of doing a particle physics calculation in all its gory detail, we start with a plausible guess and impose requirements based on what we know. Eventually, we have the right answer pulled up “by its own bootstraps”: the only answer the calculation could have, without actually doing the calculation.

This method works very well, but so far it’s only been applied to certain kinds of calculations, involving mathematical functions called polylogarithms. More complicated calculations involve a mathematical object called an elliptic curve, and until very recently it wasn’t clear how to bootstrap them. To get people thinking about it, my colleagues Hjalte Frellesvig and Andrew McLeod asked the Carlsberg Foundation (yes, that Carlsberg) to fund a mini-conference. The idea was to get elliptic people and bootstrap people together (along with Hjalte’s tribe, intersection theory people) to hash things out. “Jumpstart people” are not a thing in physics, so despite the title they were not invited.

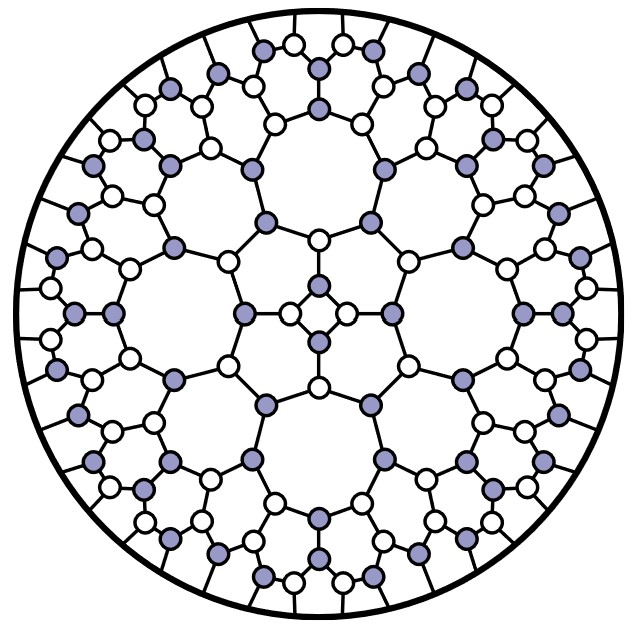

Having the conference so soon after the yearly Elliptics meeting had some strange consequences. There was only one actual duplicate talk, but the first day of talks all felt like they would have been welcome additions to the earlier conference. Some might be functioning as “overflow”: Elliptics this year focused on discussion and so didn’t have many slots for talks, while this conference despite its discussion-focused goal had a more packed schedule. In other cases, people might have been persuaded by the more relaxed atmosphere and lack of recording or posted slides to give more speculative talks. Oliver Schlotterer’s talk was likely in this category, a discussion of the genus-two functions one step beyond elliptics that I think people at the previous conference would have found very exciting, but which involved work in progress that I could understand him being cautious about presenting.

The other days focused more on the bootstrap side, with progress on some surprising but not-quite-yet elliptic avenues. It was great to hear that Mark Spradlin is making new progress on his Ziggurat story, to hear James Drummond suggest a picture for cluster algebras that could generalize to other theories, and to get some idea of the mysterious ongoing story that animates my colleague Cristian Vergu.

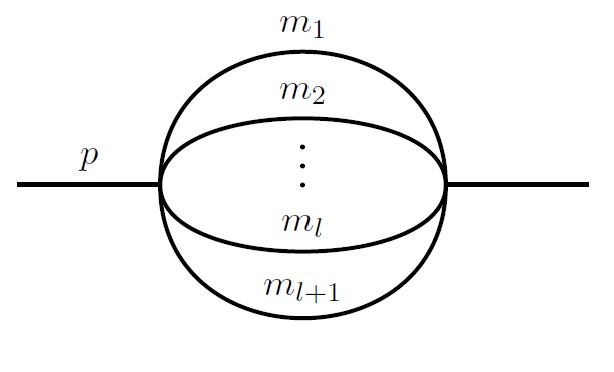

There was one thing the organizers couldn’t have anticipated that ended up throwing the conference into a new light. The goal of the conference was to get people started bootstrapping elliptic functions, but in the meantime people have gotten started on their own. Roger Morales Espasa presented his work on this with several of my other colleagues. They can already reproduce a known result, the ten-particle elliptic double-box, and are well on-track to deriving something genuinely new, the twelve-particle version. It’s exciting, but it definitely makes the rest of us look around and take stock. Hopefully for the better!