“Grand Unified Theory” and “Theory of Everything” may sound like meaningless grandiose titles, but they mean very different things.

In particular, Grand Unified Theory, or GUT, is a technical term, referring to a specific way to unify three of the fundamental interactions: electromagnetism, the weak force, and the strong force.

In contrast, guts unify the two fundamental intestines.

Those three forces are called Yang-Mills forces, and they can all be described in the same basic way. In particular, each has a strength (the coupling constant) and a mathematical structure that determines how it interacts with itself, called a group.

The core idea of a GUT, then, is pretty simple: to unite the three Yang-Mills forces, they need to have the same strength (the same coupling constant) and be part of the same group.

But wait! (You say, still annoyed at the pun in the above caption.) These forces don’t have the same strength at all! One of them’s strong, one of them’s weak, and one of them is electromagnetic!

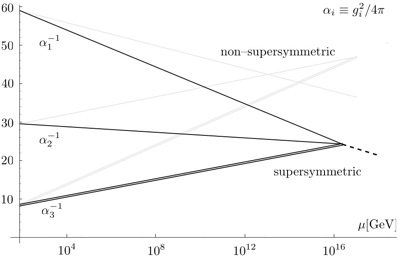

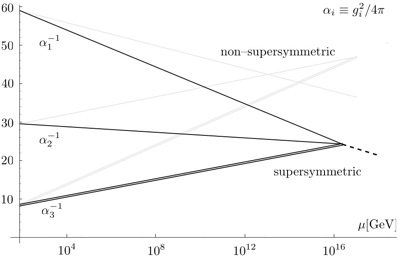

As it turns out, this isn’t as much of a problem as it seems. While the three Yang-Mills forces seem to have very different strengths on an everyday scale, that’s not true at very high energies. Let’s steal a plot from Sweden’s Royal Institute of Technology:

Why Sweden? Why not!

What’s going on in this plot?

Here, each  represents the strength of a fundamental force. As the force gets stronger,

represents the strength of a fundamental force. As the force gets stronger,  gets bigger (and so

gets bigger (and so  gets smaller). The variable on the x-axis is the energy scale. The grey lines represent a world without supersymmetry, while the black lines show the world in a supersymmetric model.

gets smaller). The variable on the x-axis is the energy scale. The grey lines represent a world without supersymmetry, while the black lines show the world in a supersymmetric model.

So based on this plot, it looks like the strengths of the fundamental forces change based on the energy scale. That’s true, but if you find that confusing there’s another, mathematically equivalent way to think about it.

You can think about each force as having some sort of ultimate strength, the strength it would have if the world weren’t quantum. Without quantum mechanics, each force would interact with particles in only the simplest of ways, corresponding to the simplest diagram here.

However, our world is quantum mechanical. Because of that, when we try to measure the strength of a force, we’re not really measuring its “ultimate strength”. Rather, we’re measuring it alongside a whole mess of other interactions, corresponding to the other diagrams in that post. These extra contributions mean that what looks like the strength of the force gets stronger or weaker depending on the energy of the particles involved.

(I’m sweeping several things under the rug here, including a few infinities and electroweak unification. But if you just want a general understanding of what’s going on, this should be a good starting point.)

If you look at the plot, you’ll see the forces meet up somewhere around 10^16 GeV. They miss each-other for the faint, non-supersymmetric lines, but they meet fairly cleanly for the supersymmetric ones.

So (at least if supersymmetry is true), making the Yang-Mills forces have the same strength is not so hard. Putting them in the same mathematical group is where things get trickier. This is because any group that contains the groups of the fundamental forces will be “bigger” than just the sum of those forces: it will contain “extra forces” that we haven’t observed yet, and these forces can do unexpected things.

In particular, the “extra forces” predicted by GUTs usually make protons unstable. As far as we can tell, protons are very long-lasting: if protons decayed too fast, we wouldn’t have stars. So if protons decay, they must do it only very rarely, detectable only with very precise experiments. These experiments are powerful enough to rule out most of the simplest GUTs. The more complicated GUTs still haven’t been ruled out, but it’s enough to make fewer people interested in GUTs as a research topic.

What about Theories of Everything, or ToEs?

While GUT is a technical term, ToE is very much not. Instead, it’s a phrase that journalists have latched onto because it sounds cool. As such, it doesn’t really have a clear definition. Usually it means uniting gravity with the other fundamental forces, but occasionally people use it to refer to a theory that also unifies the various Standard Model particles into some sort of “final theory”.

Gravity is very different from the other fundamental forces, different enough that it’s kind of silly to group them as “fundamental forces” in the first place. Thus, while GUT models are the kind of thing one can cook up and tinker with, any ToE has to be based on some novel insight, one that lets you express gravity and Yang-Mills forces as part of the same structure.

So far, string theory is the only such insight we have access to. This isn’t just me being arrogant: while there are other attempts at theories of quantum gravity, aside from some rather dubious claims none of them are even interested in unifying gravity with other forces.

This doesn’t mean that string theory is necessarily right. But it does mean that if you want a different “theory of everything”, telling physicists to go out and find a new one isn’t going to be very productive. “Find a theory of everything” is a hope, not a research program, especially if you want people to throw out the one structure we have that even looks like it can do the job.