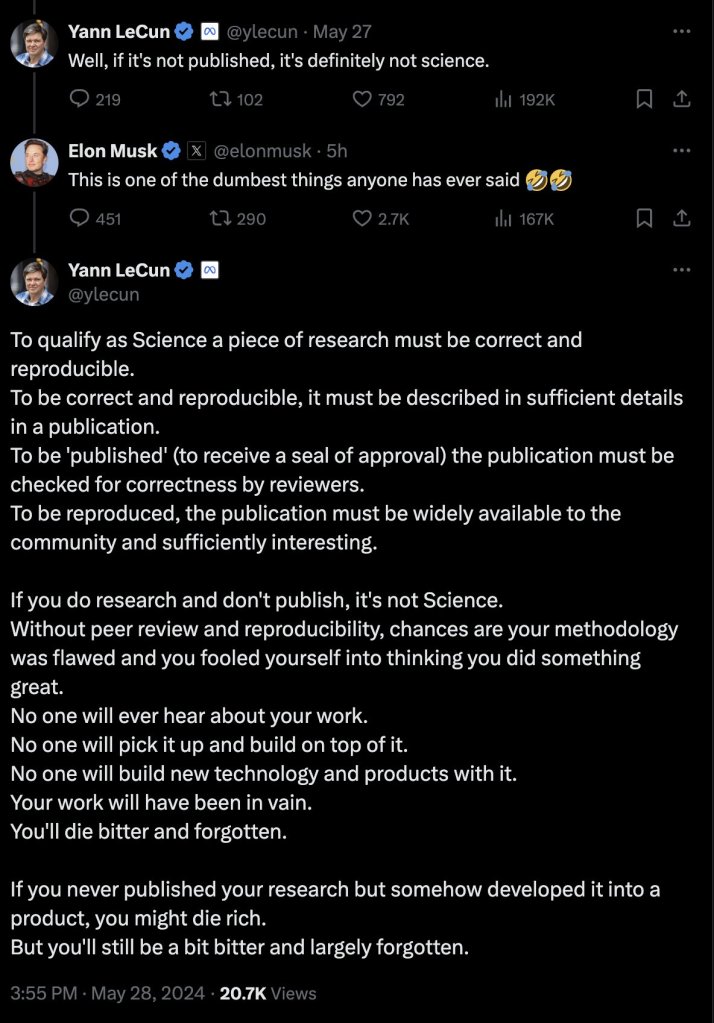

Seen on Twitter:

As is traditional, twitter erupted into dumb arguments over this. Some made fun of Yann LeCun for implying that Elon Musk will be forgotten, which despite any other faults of his seems unlikely. Science popularizer Sabine Hossenfelder pointed out that there are two senses of “publish” getting confused here: publish as in “make public” and publish as in “put in a scientific journal”. The latter tends to be necessary for scientists in practice, but is not required in principle. (The way journals work has changed a lot over just the last century!) The former, Sabine argued, is still 100% necessary.

Plenty of people on twitter still disagreed (this always happens). It got me thinking a bit about the role of publication in science.

When we talk about what science requires or doesn’t require, what are we actually talking about?

“Science” is a word, and like any word its meaning is determined by how it is used. Scientists use the word “science” of course, as do schools and governments and journalists. But if we’re getting into arguments about what does or does not count as science, then we’re asking about a philosophical problem, one in which philosophers of science try to understand what counts as science and what doesn’t.

What do philosophers of science want? Many things, but a big one is to explain why science works so well. Over a few centuries, humanity went from understanding the world in terms of familiar materials and living creatures to decomposing them in terms of molecules and atoms and cells and proteins. In doing this, we radically changed what we were capable of, computers out of the reach of blacksmiths and cures for diseases that weren’t even distinguishable. And while other human endeavors have seen some progress over this time (democracy, human rights…), science’s accomplishment demands an explanation.

Part of that explanation, I think, has to include making results public. Alchemists were interested in many of the things later chemists were, and had started to get some valuable insights. But alchemists were fearful of what their knowledge would bring (especially the ones who actually thought they could turn lead into gold). They published almost only in code. As such, the pieces of progress they made didn’t build up, didn’t aggregate, didn’t become overall progress. It was only when a new scientific culture emerged, when natural philosophers and physicists and chemists started writing to each other as clearly as they could, that knowledge began to build on itself.

Some on twitter pointed out the example of the Manhattan project during World War II. A group of scientists got together and made progress on something almost entirely in secret. Does that not count as science?

I’m willing to bite this bullet: I don’t think it does! When the Soviets tried to replicate the bomb, they mostly had to start from scratch, aside from some smuggled atomic secrets. Today, nations trying to build their own bombs know more, but they still must reinvent most of it. We may think this is a good thing, we may not want more countries to make progress in this way. But I don’t think we can deny that it genuinely does slow progress!

At the same time, to contradict myself a bit: I think you can think of science that happens within a particular community. The scientists of the Manhattan project didn’t publish in journals the Soviets could read. But they did write internal reports, they did publish to each other. I don’t think science by its nature has to include the whole of humanity (if it does, then perhaps studying the inside of black holes really is unscientific). You probably can do science sticking to just your own little world. But it will be slower. Better, for progress’s sake, if you can include people from across the world.

And I love this turn towards metascience on your blog. You should write more about metascience! It’s something I’m trying to cover on my own blog.

I actually have a draft of an article which I’ve been sitting on over a year, which is gives a counter argument to this widely-read article which argued against peer-review: https://www.experimental-history.com/p/the-rise-and-fall-of-peer-review

I believe journals and peer review have many problems, but do play important role, namely providing a means of surfacing the highest quality articles. Trying to find good articles on a preprint servers, by contrast, can be hard – like finding a needle in a haystack – and its getting harder over time due to paper mills and the exponential increase in papers published per year.

LikeLike

The metascience theme is something I keep returning to. I don’t think it’s possible to go through the academic system and not have opinions about this stuff!

Regarding peer review, I think it varies a lot sub-field to sub-field. Amplitudes is tiny enough that in a journal club we can typically at least lightly discuss every paper put up on arXiv each week. Obviously that won’t be true for anything related to medicine or ML.

Have you heard of arXiv overlay journals? Basically, groups that just do the peer review part and not the publication part, listing the results of the reviews online. That can do the filtering thing for fields that need it without all the other infrastructure.

For you personally, when you’re trying to keep up with the topics you care about, do you mostly do it by checking what got published each time a journal comes out? Or do you more often run into new papers via social media?

LikeLike

I agree that to be science you need to document your findings in a way that is possible to reproduce. And, it is desirable for the general public, and for people engaged in the enterprise of science generally, to public scientific results widely. But is it necessary . . . . I don’t think so.

There are also sorts of reasons that one might do scientific research for a prolonged period of time, and develop it considerably, without releasing it to the public, and peer review can be helpful, but it isn’t as if peer review in scientific journals is terribly rigorous anyway. It is more than copy-editing, but it is less than a global analysis of whether it holds up against all of the existence relevant literature and all the objections you can raise to an approach either.

Honestly, I’d favor a peer review system that is more rigorous in many respects – for example, I’d like it if it was par for the course to make a strong case for ruling out any known physics explanation in any paper purporting to explain phenomena with new physics.

Lack of publication and peer review increases the risk that a mistake will not be found, which imposes a greater duty to self-discipline your monitoring of the accuracy of your own work, but it isn’t a make or break factor.

Lots of big papers are embargoed until some symbolic date, or have data analyzed while it is still encrypted until the very last moment (like the muon g-2 data), but the work is still science when it is being done prior to the publication date.

There are lots of reasons to postpone publication. Suppose, for example, that the larger scientific community isn’t ready for your scientifically rigorous developments just yet and that revealing them would cost you your job (see, e.g., early modern heliocentric astronomers or the Scopes Monkey trial). Or, alternatively, that no one finds you work interesting enough to publish (a lot of the work on chaos and fractals languished in obscurity virtually unread for many decades). Or, that if your discovery were released that it would trivially point the path to a deadly weapon that your enemies could use against you (the Manhattan project and a lot of the work being done on crytography in the NSA). Or, that you have an exclusive business method that relies upon your discovery in a trivial way and that if you didn’t keep it a trade secret, your business which is your livelihood would become unprofitable (perhaps solid state physics rule that shortcuts custom designing new materials). Or, that revealing some new species you discovered in a journal article would likely lead to the extinction of that species (e.g. you discover a cryptid).

Efforts to replicate the scientific work of others is science too, even if not all of those replication efforts are published because publishers don’t care because it doesn’t advance science as obviously as a new discovery.

Not publishing a scientific result may delay the benefit it provides to future scientists and the larger world, but truth delayed is still better than truth never learned because doing science and publishing it could cause to much harm. And, if a significant delay in publication doesn’t cause it to cease to be science, then publication can’t be what makes it science.

LikeLike

“It is more than copy-editing” – or sometimes less, in my experience!

I do want to push back against your idea that a paper proposing new physics should make a strong case that it can’t be explained with existing physics. As I think I’ve argued to you before, you’re misdiagnosing the problem. When someone proposes new physics to solve a problem, they’re doing it because some past paper identified the phenomenon as a problem by using state of the art methods to model something using existing physics and failing to. That’s what every n-sigma deviation is, a statistical argument that something is inconsistent with known physics. If you think people are too lax in identifying those issues, the blame has to be on the papers that report how many sigmas of deviation something has, not in the papers that later propose novel mechanisms to explain the deviations.

As to your general point, we’re talking about how to most usefully define a word, so it will always be a matter of degree. And we’re talking about how to define a word that describes a big historical process, so we should mostly think of this as a description of systematic processes, not of one-off actions. “This one person did X” doesn’t count as science or non-science, but “this community systematically does X” can.

I don’t think delays matter all that much, as long as they’re not lifetimes worth. But fundamentally, if something has to be discovered multiple times, as the bomb had to or as many trade secrets have to, then you’re giving up one of the core things that make science work. And I think systems that systematically do that kind of thing, like military and certain types of corporate research, probably should be thought of as deviating from full-fledged science for that reason.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“That’s what every n-sigma deviation is, a statistical argument that something is inconsistent with known physics.”

Usually a paper with a deviation is doing to identify a measured value of something, and several sources of known, quantifiable error (typically statistical uncertainty and systemic measurement error, but sometimes theory uncertainty due to things like truncations of infinite series approximations).

Often, a paper reporting an anomaly will then also conclude by saying something like, “this could be due to unquantifiable systemic or theoretical errors such as . . . . or could be due to new physics.”

Experience shows that overwhelmingly, these anomalies end up getting resolved with more data, or a serious overlooked or underestimated sources of systemic error (e.g. OPERA’s superluminal neutrinos, or reliance on flawed old data in the muonic proton radius puzzle case), or a theory, analysis and framing of the issue error (e.g. the apparent indications of lepton universality violation, or the muon g-2 anomaly).

In the last 30-40 years, the only time I can think of that new physics was ever actually the answer in HEP was the discovery that neutrinos had mass and oscillate.

But it seems like new physics proposal papers that haven’t panned out yet seem to outnumber papers that try to explain anomalies with the kinds of resolutions that usually end up winning the day, maybe 50-1. This is so even though the need for any new physics in HEP is not very compelling, to the point where scientists are pouncing like hyenas on every 2.4 sigma tension that shows up somewhere for want of anything better to work with.

Yeah, I feel their pain.

For example, the new discovery by BESIII that the X(2370) involved a finding that it was a 0-+ quantum number hadron with a mass of 2395 MeV, when a theory calculation in 2019 predicted that the lightest glueball with a 0-+ quantum number hadron would have a mass of 2395 MeV! And QCD calculations are closest to being more art than science with frequent anomalous calculation results. Also, the best alternative to a glueball interpretation of X(2370) would have been a purely SM tetraquark analysis. Not much room for new physics there.

Does this mean that nobody should propose new physics? No.

Does it mean that we should have a system the supports researchers looking for old physics resolutions of anomalies much more vigorously than researchers advocating new physics resolutions, if we want to maximize scientific progress? Maybe so.

Ironically, in the one area where we know to a near certainty that new physics really is required, the astrophysics of dark matter and dark energy phenomena, while there are certainly new physics papers, proportionately, they seem to involve a much smaller proportion the the output, relative to data generation and analysis and exploration of any possible non-new physics explanation that can be found for a particular result. Maybe 2-1 instead of 50-1. How does that make sense?

LikeLike

I think you’re overlooking a key question here, namely the kind of expertise needed for each type of analysis.

Deviations from the SM typically go away for one of three reasons:

A mistake in the experimental analysis or a flaw in the experiment itself. This is very difficult to identify unless you are on the team of the experiment that reported the result, otherwise you don’t have the full details about what happened no matter how diligently the initial team tries to report things.

Major theoretical progress. In a lot of these examples this is progress in QCD, new lattice techniques and people pushing the state of the art, or new techniques for other QCD effects like parton showers.

There are more people capable of 3. than 2., but not a lot more. It’s still a very specialized sort of capability, requiring experience, ability, and interest. Changing the balance of funding won’t change the speed of progress here very much, it’s a question of what individual people have the expertise to do. You can increase the numbers of grad students in different areas a bit, but theorists can only productively train so many people. You can’t bootstrap this kind of expertise from nowhere.

In the end, most people proposing BSM scenarios don’t have the expertise to contribute to state-of-the-art non-perturbative QCD, nor are they close enough to the experiments to resolve experimental errors.

So if you want less of that kind of speculation, I think the only way to get there is for there to just be fewer physicists. I’m…sympathetic to that. At least, I think ideally there should be more fluidity between areas, with people being able to move on when an area is not being productive. But that goes up against human nature in a variety of ways, both in that people get passionate about what they’re working on and don’t want to shift and in that expertise atrophies without regular practice and involvement with the scientific literature.

So I don’t know. I have to hope all of this will be much simpler when humans aren’t the main engine of scientific progress anymore.

LikeLike

I just realized your example of astro vs. collider physics actually provides a pretty clean case of what I’m talking about. Astronomy is not easy, but it is something humans have been doing for longer than they have been doing science itself, and a field where amateurs can still make useful contributions. There are a lot of people capable of contributing something useful to observational astronomy, or to data analysis. Many such people never even learn quantum field theory. In contrast, nonperturbative quantum field theory is something very few people understand, some might even argue it’s something nobody understands. The number of people capable of improving the QCD contributions to an apparent SM deviation is as such going to be vastly smaller than the number of people capable of improving observation and data analysis for an astrophysical puzzle, so it shouldn’t be surprising that one area has a lot more papers than the other.

LikeLike