In particle physics, we almost always use approximations.

Often, we assume the forces we consider are weak. We use a “coupling constant”, some number written or

or

, and we assume it’s small, so

is greater than

is greater than

. With this assumption, we can start drawing Feynman diagrams, and each “loop” we add to the diagram gives us a higher power of

.

If isn’t small, then the trick stops working, the diagrams stop making sense, and we have to do something else.

Except for some times, when everything keeps working fine. This week, along with Simon Caron-Huot, Lance Dixon, Andrew McLeod, and Georgios Papathanasiou, I published what turned out to be a pretty cute example.

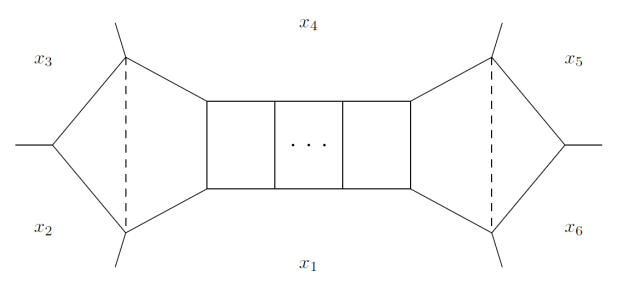

We call this fellow . It’s a family of diagrams that we can write down for any number of loops: to get more loops, just extend the “…”, adding more boxes in the middle. Count the number of lines sticking out, and you get six: these are “hexagon functions”, the type of function I’ve used to calculate six-particle scattering in N=4 super Yang-Mills.

The fun thing about is that we don’t have to think about it this way, one loop at a time. We can add up all the loops,

times one loop plus

times two loops plus

times three loops, all the way up to infinity. And we’ve managed to figure out what those loops sum to.

The result ends up beautifully simple. This formula isn’t just true for small coupling constants, it’s true for any number you care to plug in, making the forces as strong as you’d like.

We can do this with because we have equations relating different loops together. Solving those equations with a few educated guesses, we can figure out the full sum. We can also go back, and use those equations to take the

s at each loop apart, finding a basis of functions needed to describe them.

That basis is the real reward here. It’s not the full basis of “hexagon functions”: if you wanted to do a full six-particle calculation, you’d need more functions than the ones is made of. What it is, though, is a basis we can describe completely, stating exactly what it’s made of for any number of loops.

We can’t do that with the hexagon functions, at least not yet: we have to build them loop by loop, one at a time before we can find the next ones. The hope, though, is that we won’t have to do this much longer. The basis covers some of the functions we need. Our hope is that other nice families of diagrams can cover the rest. If we can identify more functions like

, things that we can sum to any number of loops, then perhaps we won’t have to think loop by loop anymore. If we know the right building blocks, we might be able to guess the whole amplitude, to find a formula that works for any

you’d like.

That would be a big deal. N=4 super Yang-Mills isn’t the real world, but it’s complicated in some of the same ways. If we can calculate there without approximations, it should at least give us an idea of what part of the real-world answer can look like. And for a field that almost always uses approximations, that’s some pretty substantial progress.

Does this sum of terms of terms have any physical meaning? That is, is there a physical process in N=4 super Yang-Mills where only these diagrams are relevant, or only these diagrams plus other terms that have an analytic expression?

LikeLike

There isn’t a physical process or limit in which these diagrams dominate, no. (We did check a few limits that seemed appropriate, but none had this as the dominant contribution.) Currently it’s mostly interesting as a toy model for the full function space.

LikeLike

Very interesting result, thanks for sharing!

By the way, wouldn’t you expect singularities for some values of the coupling constant? Do you see them in your Omega? Or would they appear in some other functions of the basis?

LikeLike

I don’t think you would expect singularities in the coupling constant in this theory. (One of the nice things about planar N=4 is that there are essentially no nonperturbative corrections to the perturbative expansion: no renormalons since it’s a conformal theory, and instantons are suppressed in the planar limit.)

LikeLike

“so \alpha is less than \alpha^2 is less than \alpha^3.”

Don’t you mean: “so \alpha is bigger than \alpha^2 is bigger than \alpha^3.”?

LikeLike

Thanks! I’ve fixed it.

LikeLike